For the love of the game

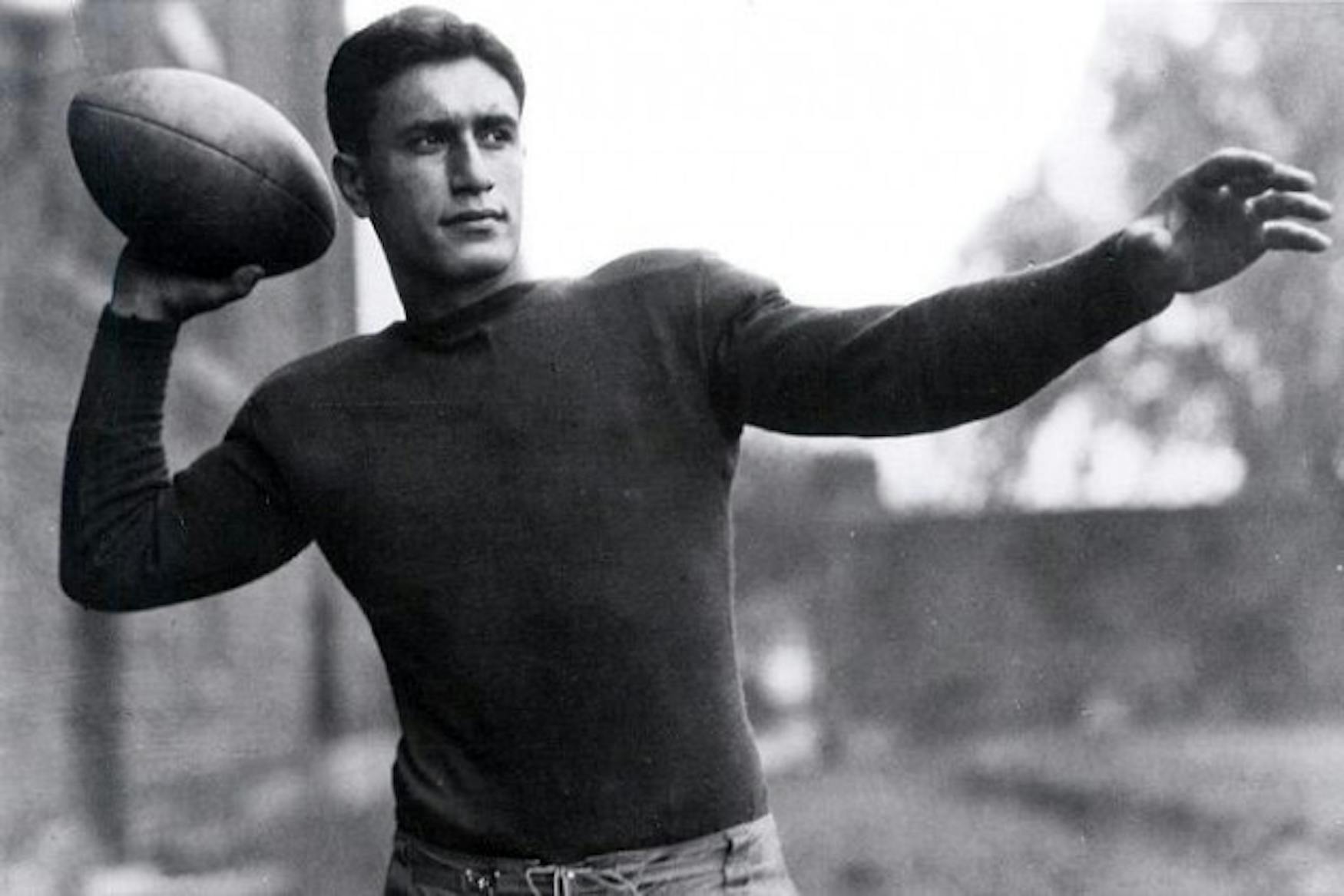

Benny Friedman led a storied career at the helm of Judges football

While a University of Michigan All-American quarterback and New York Giants star, Benny Friedman also served as the only football coach that Brandeis has ever known.

He signed on to the role in 1950, preparing to build a dynasty.

Just nine years later, the program collapsed, and in its wake, the once-resurgent squad was relegated to the history books.

Friedman, a son of Jewish immigrants from Cleveland, Ohio, was the 1926 Big Ten Most Valuable Player.

He earned the Chicago Tribune Silver Football Award, a tribute whose significance is equivalent to the Heisman Trophy today.

The rising quarterback soon made his mark in the National Football League in 1928, heading the league in passing and rushing touchdowns and overall scoring, as well as extra points.

He went on to lead a productive career at the helm of the New York Giants' offense for three years.

After his playing days, though, Friedman set out on a greater mission. He came to coach the Brandeis football team in 1950.

Ed Manganiello '54, a two-time captain for the Judges, described Friedman's desire to promote the game of Brandeis football.

"Benny Friedman's hope was to make Brandeis the Jewish Notre Dame of college football," he said. "He wanted to transform the influence that the Judges had on the game."

Friedman's role at the University, however, expanded far beyond his head coaching duties.

As athletic director, Friedman oversaw the building of the Joseph M. Linsey Sports Center and its pool, a track on Gordon Field and four outdoor tennis courts.

He was a man that looked to increase the influence that Brandeis athletics could have on the collegiate sporting world.

Friedman also became a prolific fundraiser for Brandeis. He was known for his eloquent speeches, frequently persuading donors to give to Brandeis in the early days of the University's existence.

Dick Bergel '57, running back and member of the Brandeis Hall of Fame, stated that Friedman's main goal was to capitalize on his speaking ability and image to promote Brandeis as a renowned sporting institution.

"Benny was a great orator," said Bergel. "He used this ability to tack onto the school's popularity in the Jewish community and also cement his image as one of the greatest Jewish athletes of all time."

Bergel confirmed that due to Friedman's up-tempo offense and persistent recruitment, the Judges soon became a household name in the Boston area.

"In the beginning, no one knew what Brandeis was or even how to spell it," he said. "But we became splashed across the headlines of local newspapers because of who we played and how we did."

Brandeis football posted its first winning record in 1952 with a crucial victory against Northeastern University, and from there they continued a sustained run of success until 1955. The Judges earned a 5-3 record during the 1955 season, defeating regional powerhouses such as the University of Massachusetts and University of New Hampshire.

Bergel stated that this success led to a constant influx of donations, and, in turn, served as a principal factor in the survival of the football team,

"This was publicity the University needed in total, and in particular, the athletic programs really encouraged people to make donations," he said. "That was the most important thing that our team needed."

Friedman compiled his best season in 1957, when the Judges went 6-1, shutting out New Hampshire and Northeastern before defeating Massachusetts 47-7.

The squad, though, took a turn for the worse after this seminal season, reeling off losing seasons in 1958 and 1959.

The donations stopped, and from there, spending cuts crippled Friedman's ability to recruit new players, such as Manganiello and Bergel, which led to poor performances from the team.

The Judges then put together a 0-6-1 record in 1959, leading to a protest from students and faculty to cut the program.

According to an April 1960 issue of the Justice, Eleanor Roosevelt, a lecturer and Trustee of the University, was concerned about the negative image that these football players presented in light of the school's intellectual reputation.

"Take it from me-it is better to have no publicity at all than bad publicity," she said.

The public outcry soon overwhelmed the university administration, and it was decided, over the vocal complaints of Friedman, to end the football program.

Despite there being few reminders of Friedman's legacy, thehistory that he made was not lost on his team.

Bergel reflected that the squad, though, succeeded as long as it did due to Friedman's lasting legacy as a pioneer in thegame of football.

"We were a very tight-knit group," he said. "All of the guys hadsuch affection for Benny."

While the Judges may never step on the gridiron, Friedman and the football squad have left their footnote in Brandeis history.

Please note All comments are eligible for publication in The Justice.