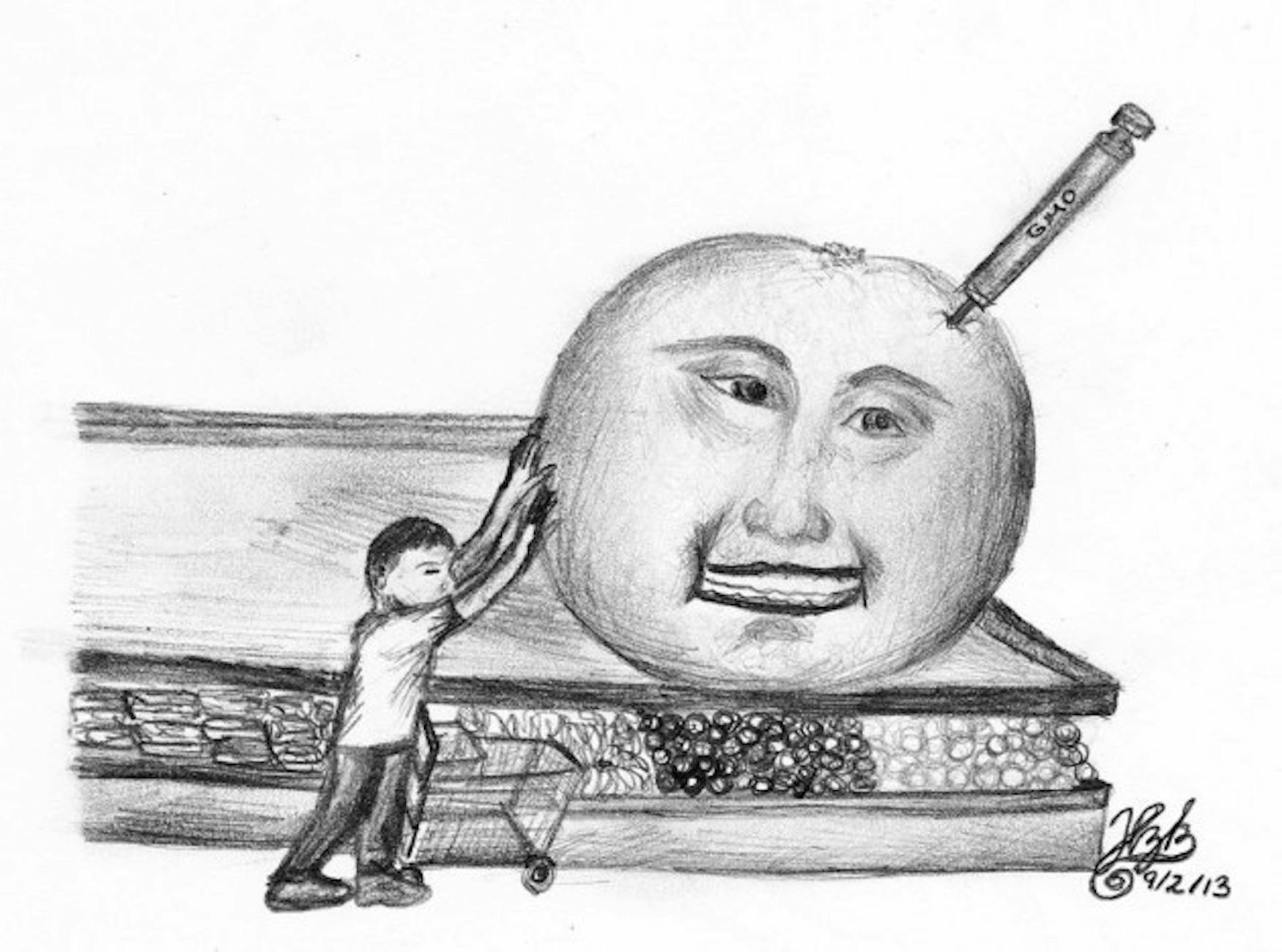

GMOs in produce present potential ethical dilemma

In recent political news, our U.S. legislators shot down a law forcing companies to label all foods that contain genetically modified organisms. According to the World Health Organization, a genetically modified food is one that has been modified by inserting a gene from a different organism into its genetic code. This process allows businesses to profit from a food that was not made naturally.

GM research is a very new science and the real health risks of consuming foods that are not naturally-occurring have not been confirmed. Research from the U.S. National Library of Medicine further reveals how some GM foods may have toxic effects on the hormonally-sensitive parts of our bodies, but that many more years of research must be conducted before we know for sure. According to he Grocery Manufacturer Association, 80 percent of the conventional processed foods we eat in America contain GMOs. Consumers have been unknowingly eating them and in light of recent news, this could be detrimental for people who have dietary restrictions.

In this last orange season, a bacterium called C. liberibacter destroyed nine percent of the total orange groves in Florida. It sounds like a very small portion; but, Florida's orange industry is the second largest in the world and this loss has put even more pressure on the farmers. Given the hope that genetic modification could potentially produce orange trees that are resilient to this devastating bacterium, farmers have begun working with GMO researchers.

Dr. William O. Dawson at the University of Florida has been a key researcher, testing a dozen different bacteria-fighting genes to add to oranges. The most successful gene was doomed from the beginning and came from the least comforting source: the pig. Dawson's article states that there is nothing scientifically dangerous about this; however, it does present an ethical dilemma for all the non-pig eaters of the world. From a religious standpoint, there are Muslims, Jews and Hindus as well as vegetarians and vegans, all of whom conservatively do not consume pigs or pork products. If this technology ends up passing the muster of our nation's legal system, will genetically modified oranges become off-limits for all of these groups? Without legislation mandating that companies label foods containing GMOs, will these groups of people be able to safely eat oranges?

Why have we as a society come to a point where even our fruits and vegetables are genetically related to pork products? How is this accepted as the best solution to stop the destruction caused by C. liberibacter? This bacterium has evolved to become so strong that it is resilient to all of the various pesticides, herbicides, fungicides and other chemicals that are sprayed on orange groves. It is our own fault for having exposed our environment to so many deleterious chemicals that by the process of natural selection, C. liberibacter is now a formidable opponent. If this unsettling research becomes our nation's last resort to save the orange groves of Florida, what could that mean for all of the other agricultural sectors in America that are threatened by deadly bacteria?

Only a non-pork eater himself can dictate whether or not this type of orange will be ethically sound to consume. But if the U.S. government does not give its people the option to decide by not mandating companies to label their foods, will we be able to eat oranges anymore?

When it comes to oranges, which are so central to American life-present on breakfast tables and in little league sports snacks, genetic modification is a frightening solution. If researchers cannot stop C. liberibacter and it eradicates the fruit altogether, will we survive without the orange?

Tampering with Mother Nature's creations for temporary fixes to our agricultural problems does not seem to be the best solution. If I may present an alternate solution to the orange quandary, I would suggest all cities adopt a community-supported agriculture, which is much smaller in scale and more sustainably sound for our environment.

CSA is a fairly new system for which communities come together to fund and support local, organic, seasonal produce, which ultimately combats this unnatural demand most societies have for wanting everything available to them at all times. We, as Brandeis students, are fortunate to have multiple CSAs around Waltham that support a significant number of people. But if we expand this sustainable system to a national level and cater to this mindset of only eating produce that is in season to change our demanding dietary needs, could that be the easy solution to the case of the Florida oranges?

*

Please note All comments are eligible for publication in The Justice.