Deepening American history

History is subjective—we learn what we do about our country’s past because someone else, some nebulous authoritative force, decided it was worth recording and knowing. Who gets to make these highly political decisions about our collective national memory? Part of the answer is found in the work of historians like Alan Taylor Ph.D. ’86, who devote their lives to bringing light to what actually might have happened in our nation’s history.

This April, Taylor was awarded his second Pulitzer Prize for his book The Internal Enemy: Slavery and War in Virginia, 1772-1832. The citation of the Pulitzer committee acclaims Internal Enemy as “a meticulous and insightful account of why runaway slaves in the American colonial era were drawn to the British side as potential liberators.”

Taylor is one of the nation’s most distinguished historians in the era of Colonial America, the American Revolution and the early U.S. republic. Taylor has taught for 20 years in the history department of the University of California, Davis. In August, Taylor will begin teaching at the University of Virginia as the Thomas Jefferson Memorial Foundation Professor Chair in History.

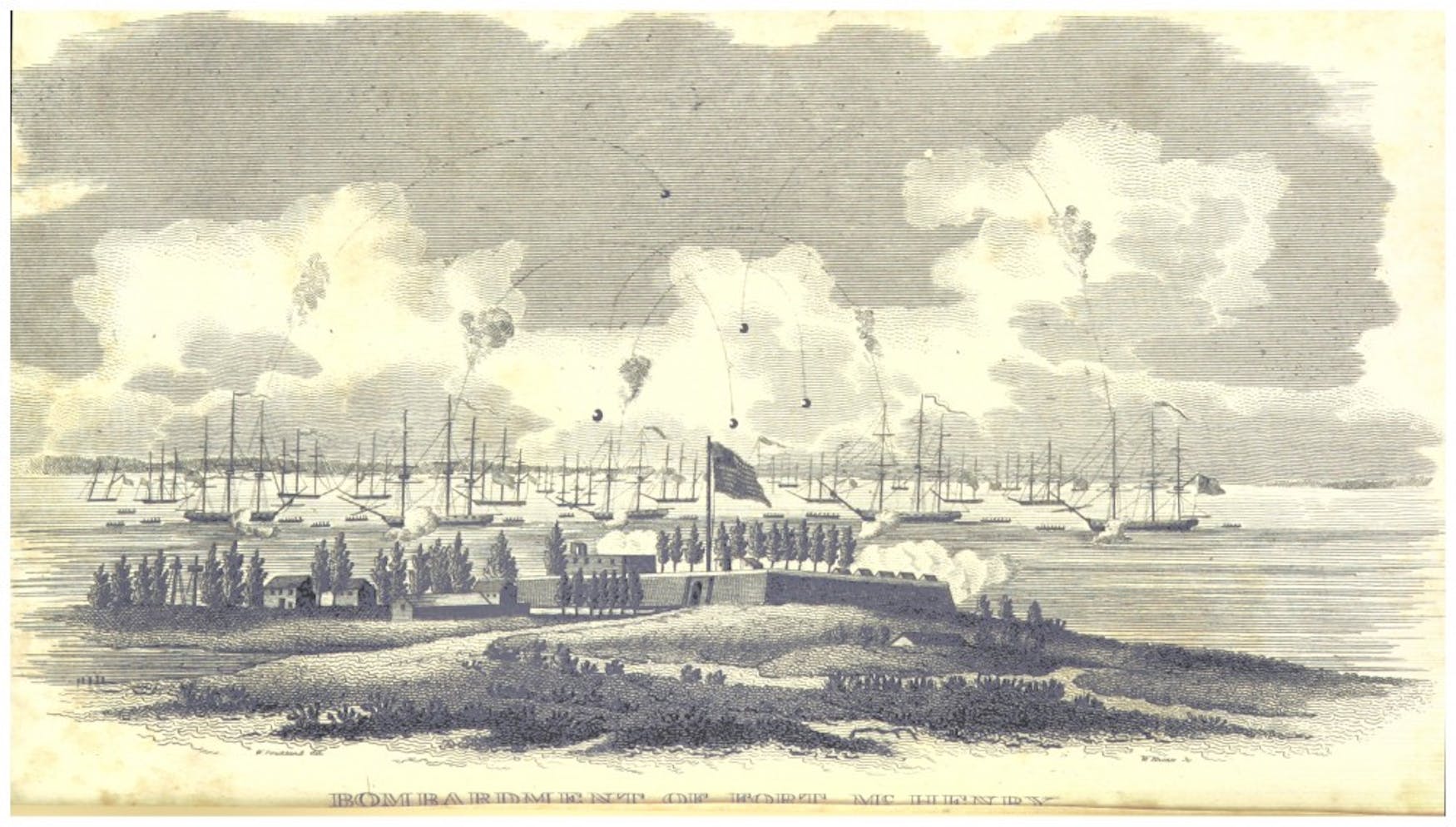

Taylor’s book tells the story of 3,000 slaves in the Chesapeake Bay region who exploited wartime disorder to escape to freedom by fleeing and joining the British to fight against Americans in the War of 1812.

In Internal Enemy, Taylor sets the stage for a little-known footnote of history by describing what was an especially tragic time for enslaved African-Americans. Masses of common white men slowly began to gain property, which eventually led to the breaking up of the largest plots of land and large concentrations of enslaved people.

“Slavery in Virginia became much more dispersed, and well-established communities of enslaved people were broken up. This is putting great pressure on their families and their communities,” Taylor said. In 1996, Taylor received his first Pulitzer Prize for his book William Cooper’s Town: Power and Persuasion on the Frontier of the Early American Republic. Cooper’s Town tells the story of William Cooper, who was a judge and the founder of Cooperstown in a then-forested area of New York.

The history of this small community continues with the life of Cooper’s son, David Fenmore Cooper. “David Fenmore Cooper pioneered the writing of American historical fiction with a frontier setting. He did so by drawing on memories of the Cooper’s Town of his childhood and of his father’s generation,” Taylor said.

Taylor’s historical research consistently focuses on “microhistories,” preferring to narrate subtle dynamics between individuals and small groups that are typically passed over by historians. Taylor recognizes their crucial influence on the larger political and social systems of the day. He stresses the importance of integrating these individual stories with macro-historical narratives, moving between the individual and the society on an ascending and descending scale within every chapter. Taylor continuously zooms in and out between the individual and the larger societal structures.

“You must see that the political ideals of slave owners and political leaders have consequences for ordinary people. And that the behavior and ideas of ordinary people also have an influence over their leaders,” Taylor said.

The research for Cooper’s Town and Internal Enemy was manifested differently. For Cooper’s, Taylor drew primarily from the extensive documentation that both William Cooper and his son left behind. For Internal Enemy, the experience was quite different; Taylor drew from a unique, untapped source.

After the Revolutionary War, the newly-formed U.S. government established a claims commission so masters could document their slaves that had escaped and fled to the British, and be compensated for their loss of property. “Slave owners would throw in any document that they thought would help them be compensated,” said Taylor. “There are some extraordinary descriptions of escapes, and even letters written by slaves after the war back to their former masters. No other historian has used these documents, so it was a great opportunity for me to address this challenge.”

Internal Enemy is unique because it tells the histories of marginalized people without property. Voices of landed people are historically better represented due to the extensive records they leave behind. People with property are well-convinced of their historical worth—they are confident that their lives are worthy of documentation, of interest to future generations and that their actions will have permanence after they die.

“It’s much harder to capture the lives of the enslaved people. Societies were arranged in a way that discouraged enslaved people from putting their thoughts on paper. That challenge is what drew me to telling this story,” Taylor said.

Taylor’s interest in early American history has been a strong force in his life since childhood, inspiring him to eventually pursue a doctorate at Brandeis in American History. “It goes back to when I was a kid,” Taylor said, “I was very interested in stories about Colonial America, the American revolution and the early U.S. republic.”

A common conclusion between Internal Enemy and Cooper’s Town, and of analytical historical writing in general, is the incredible importance of property within a society. According to Taylor, in Cooper’s Town, the primary tension comes from disputes over the legal ownership and distribution of land, and in Internal Enemy, it comes from the political consequences of a system that allowed human beings to be owned as property. In both cases the question becomes this—who owns property and who derives the political power that comes from owning property.

“We are certainly living in a society that has inherited social dilemmas that are derived from the property systems of the past, which redistributed land in an unequal fashion and which has treated thousands of people as property,” Taylor said.

Taylor believes that Americans questioning existing inequalities in society should consult the past in order to understand how modern structures came to be. “We live in a society where there is increasing attention to the inequality of income. And many people have questions about how that came to be. Well … there is a very long history of inequality in our country,” Taylor said.

Please note All comments are eligible for publication in The Justice.