Goya exhibit offers retrospective look

Right now at the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, viewers can see one of the most comprehensive exhibitions to date of the works of Spanish painter Francisco Goya. The exhibition, titled Goya: Order and Disorder, opened for public viewing last Sunday in the Ann and Graham Gund Gallery.

“Goya’s power was apparent to me as a teenager, when I first encountered a set of his Caprichos, etchings on view at the Worcester Art Museum,” wrote the exhibit’s curators in an introduction to the exhibition, mounted on the wall at the gallery’s entrance.

Compared to others I have seen at the MFA, the exhibition was quite large and included 170 paintings, drawings and prints. “The kernel of this exhibition was a pair of Goya drawings here at the MFA, and their thematic comparison quickly grew into this full-scale examination of the artist’s creativity across time and media,” the curators wrote.

Instead of arranging the works by medium or date completed—as the exhibition included both paintings and prints—the curators used the gallery’s series of large rooms to stage what they called a “reshuffled retrospective.” Throughout several rooms in the gallery, works were separated into thematic clusters.

Walking through the gallery, the viewer is taken through eight thematic sections—the life cycle and love; games and sport; balance; portraiture; spirituality and dreams; history; and a final summary of the artist’s defining qualities.

The first room of the gallery—and, as I discovered later, the last room—centers around an immensely-sized portrait, a fitting piece as portraiture is what originally caused Goya’s rise to prominence during his lifetime. In the first room, The “Family of the Infante Don Luis,” (1784) a portrait of oil on canvas, hung surrounded by a huge crowd of viewers.

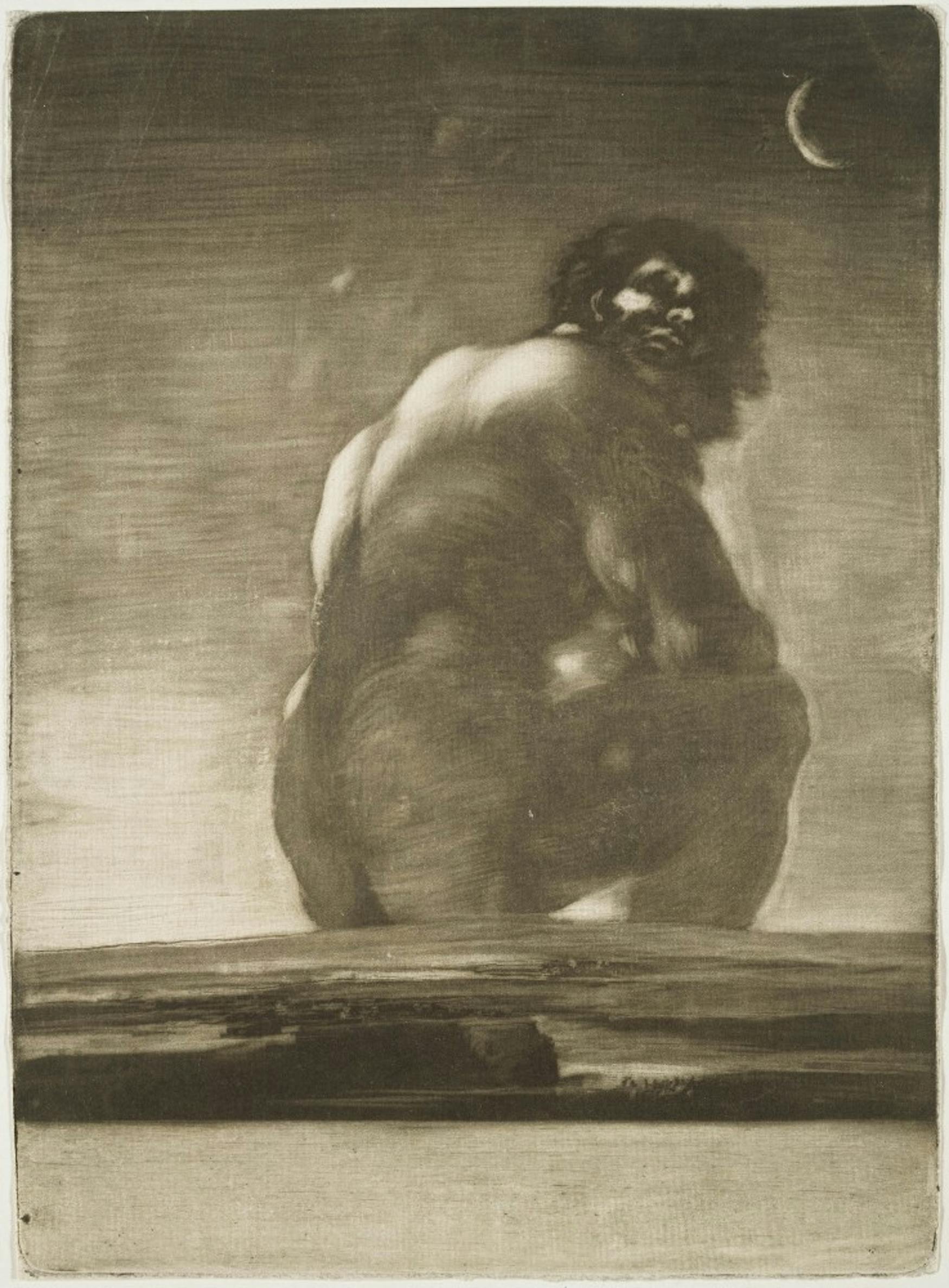

Moving into the exhibition, the viewers get to know more sides of Goya’s work; although he was most well-known for his painting, a most respectable profession during the 18th century, he was also a very talented printmaker.

During his lifetime, printmaking was considered less of a high art than painting in Spain, and so his prints were often bases for much larger paintings or tapestries—nonetheless, Order and Disorder included an impressive collection of the artist’s prints, which expanded how viewers understood the thematic development within his work and the exhibition’s organization.

After passing through the first room, the viewer walks into the life studies portion of the exhibition. In this part, collected images representing life hang around the gallery showing Goya’s study of livelihood and family life, from childhood to old age. Several prints from his Caprichos series were hung in succession, showing lovers and the range of emotions between them—tension and affection, the feelings underlying lustfulness.

Another section honed in on the theme of “play and prey,” juxtaposing images of pleasantry with images of violence and pursuit. Several repeated images in prints of women bouncing a boy into the air on a tarp, all laughing, were almost forgotten as I walked a few feet along the wall, confronted with several alarmingly detailed still life paintings of dead animals—woodcocks, hares—that led into a section of works centered around hunting.

Moving further into the exhibition, a section of works thematically focused on balance reinforced the artist’s preoccupation with order and disorder, often showing subjects in physical or emotional anguish.

A section of works of Goya’s famed portraiture followed, showcasing several members of Spanish and French families of nobility and even several works that found the same subject at different points in their life.

A most sublime and crafty portrait in this section, the 1797 work “Maria del Pilar Teresa Cateyana de Silva Alvarez de Toledo y Silva, Thirteenth Duchess of Alba,” emphasized the artist’s affinity for leaving messages in his paintings. This portrait finds the duchess standing, in traditional Spanish clothing for the time, pointing at the ground. Glancing down at the ground in the painting where she points, the viewer sees the Spanish words “Solo Goya,” or, in English, “Only Goya,” written upside-down into the dirt—so they face the duchess in the image.

The artist’s implicit proclamation that only he—only Goya—could paint as he does was one theme that the exhibition’s curators brought back in the final section of the winding gallery, which they titled “Solo Goya.” Indeed, only Goya could have rendered the thematic and technical variety of works that were on display.

The exhibition will be on view until Jan. 19.

Please note All comments are eligible for publication in The Justice.