"Organic and Natural" marketing perpetuates social divide

I recently went grocery shopping at Hannaford for the first time.

Hannaford is your classic grocery store, stocked with all the food essentials a college student on a limited budget can ask for. While slowly filling my cart up with snackable necessities such as chocolate-covered cranberries and crackers, I stumbled upon the last two aisles in the store. They had a sign above them titled “Organic and Natural,” written in golden brown against a green background using an elegant font.

The “Organic and Natural” section took almost all the food the market had to offer—the breads, cereals, bars and fruit snacks available in abundance elsewhere—and condensed the selections of each of those food types to fit solely a couple of aisles. However, the difference between the pasta in aisle four versus the pasta in the “Organic and Natural” aisle is that which the label of the latter implies: it is, by title, organic and natural – certified by the United States Department of Agriculture and enriched with more nutrients. Stock in these aisles is limited, so shopping in this section makes one feel as if what he is buying is special, as if these food selections are a rarity.

Not only were there fewer, supposedly healthier and more expensive options of all the major food categories in these aisles, but the ambience was substantially different. Whereas the other supermarket aisles were filled with items packaged in bright, eye-catching reds, oranges and yellows—colors usually used by fast-food franchises as marketing techniques to trigger one’s appetite—the design of the “Organic and Natural” section takes a different approach. These aisles’ foods were packaged in green, brown and gold undertones—reflecting a message of health, wellness and prosperity. Also, the items were arranged with more finesse, as different bins and customized labels categorized specific granola bars, teas and vitamins.

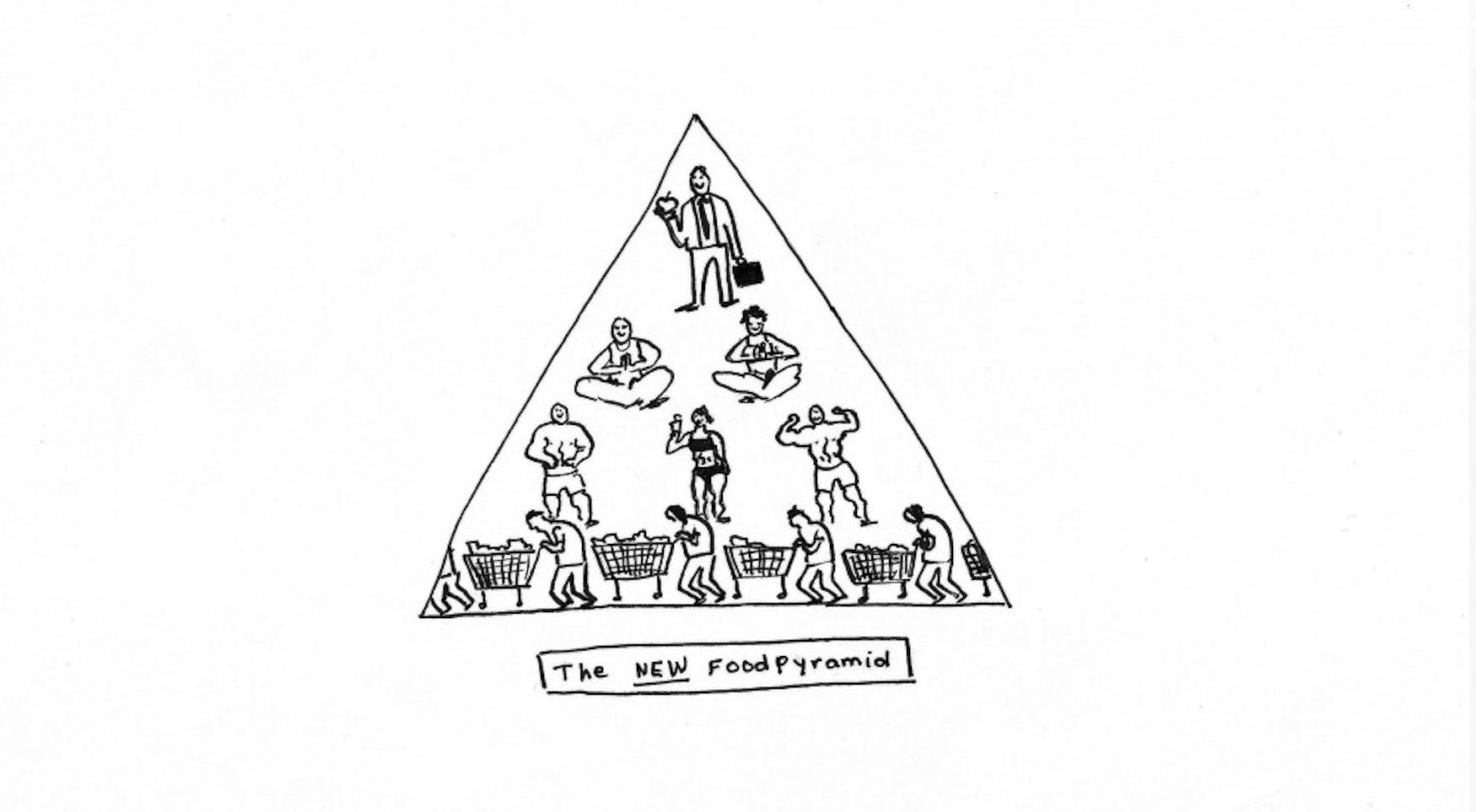

There was also a social ambience. I noticed that those who were browsing these two aisles appeared to be people able to afford these pricier “natural” selections: urban professionals, the upper-middle class mother. Also present were the more seemingly health-conscious customers, dressed in yoga pants and gym shoes, water bottles in hand—perfecting the facade of natural and healthful simplicity. Those shopping the rest of the store’s aisles seemed not to be as affluent: lower-middle class citizens, students.

While my observations were merely generalizations I had made, they tended to coincide with a 2011 study performed by the University of Washington, which found that about 15 percent of American households claim to not be earning enough money to eat the way they would like to be eating. Approximately 49 million Americans are making their food decisions based on cost.

The study further explains that while it may not be relatively expensive to eat the necessary nutrients the body needs, what is costly are the additional restrictions put on the way one meets his dietary needs—whether that be eating organic, purchasing locally grown produce.

The contrast between the “Organic and Natural” section and the rest of the supermarket reminded me of a text by Dr. Janice Williams. In the beginning of her piece, Williams writes about how health “has become increasingly seen as a matter for self-control and self-discipline… The assumption is that there must of necessity be some congruence between the social body, the psychological body and the physical body. Thus health is no longer something to do with inheritance or luck, but rather an achieved status which must be worked on and striven for.”

Society has slowly grown into this notion that one’s health is not based in large part on genetic luck—such as how strong her immune system is or if he is born with a slow metabolism—but rather on self-control and willpower, and as a result, those who are unable to meet today’s standards of what is deemed healthy often being considered inferior, regardless of why. “Health”—once a concept socially discussed in biological terms—now connotes a sort of evaluation. Poor health is equated with one’s inability to properly take care of oneself, although that’s not always the case, for genetic makeup and financial stability are also key factors.

And the fact of the matter is that the foods stocked into the “Organic and Natural” aisles are not necessarily better for one’s health, diet or wallet. An independent UK-based research project reviewed articles published in peer-reviewed journals from 1958 to 2008 on over 3500 comparisons of government certified organic versus non-organic crops. These researchers were unable to find any evidence to prove differences in nutrient content that signified a change in nutritional quality between the organic and inorganic foods—except for the fact that organic livestock products (dairy, eggs and meat) recorded higher levels of overall fats, including trans fats. Thus, shoppers buying foodstuffs solely in the “Organic and Natural” section, which are sold elsewhere in the store, are paying double the price for foods that have no proven records of actually being “better” and can actually be worse.

The success of the organic and natural franchise is in the marketing. Oftentimes those who purchase organic products are not fully aware of the composition of their food or what is the exact variation between organic and inorganic, such as the pesticides that are considered organic versus those that are not. More often, it is because the organic and natural foods seem better. If it has an organic label, it appears to have been more regulated. If it is pricier despite its smaller quantity, it looks as if it is made with better quality ingredients deserving of a higher price tag—also adds to the esteem of higher status for the consumer purchasing this product. All these considered, it is reasonable to believe that something nestled in the aisles dubbed “Organic and Natural” has to be better, right?

These components are taken into account by the company’s marketing team in order to sway the consumer by falling for these subtle brand imaging techniques, the consumer is often caught spending more for what really is the placebo effect. A study performed by the University of Southern California this year concluded that “labeling a food as organic yielded improved taste perception, regardless of its true identity. It can be seen how the placebo effect can be extended to the field of marketing.”

Despite taking these perspectives into account, I suddenly felt second-class standing in the “Organic and Natural” section in my jeans and sneakers with a shopping cart filled with Skippy peanut butter and instant soup. I wrongly felt like I did not fit in, as if all the other customers in that aisle were judging me based on my food purchases that just so happened to be practical for my current lifestyle, like I had a lack of self-control—immediately falling victim to the layout psychology of supermarkets and the bright, appetizing colors in the middle aisles. I knew better, but the stigma around the title of “organic” often tends to be much stronger than one’s sense of reality versus façade, especially if one is able to afford the “healthier” option.

So I unnecessarily swapped my Chewy Bars for Kind Bars, my Corn Flakes for oatmeal, my moderately priced food for over-priced substitutes. Because, for some reason, I preferred succumbing to trivial expectations over owning up to the practicalities of my lifestyle.

Please note All comments are eligible for publication in The Justice.