Overcoming partisan divisions is critical to democracy

This past June, Stanford University professors Shanto Iyengar and Sean J. Westwood released a new study titled “Fear and Loathing Across Party Lines: New Evidence on Group Polarization.” The findings are fascinating. In the study, subjects were given simple association tests in which a proctor told them a word, and, in as little time as possible, the subject had to state the first thing they associated with that word. The subjects were given this test twice, once comparing whites and African-Americans and once comparing Democrats and Republicans. Across the board, responses were faster and harsher for the political associations while the racial associations were made more slowly and neutrally. This test, known as the Brief Implicit Association Test, is commonly used to determine bias and prejudice against given groups. It now appears that prejudice against people of different political opinions is more common, more fierce and more acceptable than prejudice against people of different races.

Political prejudice today curiously follows many of the same trends that racial prejudice once followed. Iyengar and Westwood cite a 2008 study pointing to the growing political homogeny in American neighborhoods: one either lives in a liberal neighborhood or a conservative one, with very little middle ground. Additionally, a 2009 survey found that only nine percent of American married couples have different political views. Democrats marry Democrats, Republicans marry Republicans. Many within that nine percent reported that their parents disapproved of their marrying across the aisle or outside the party.

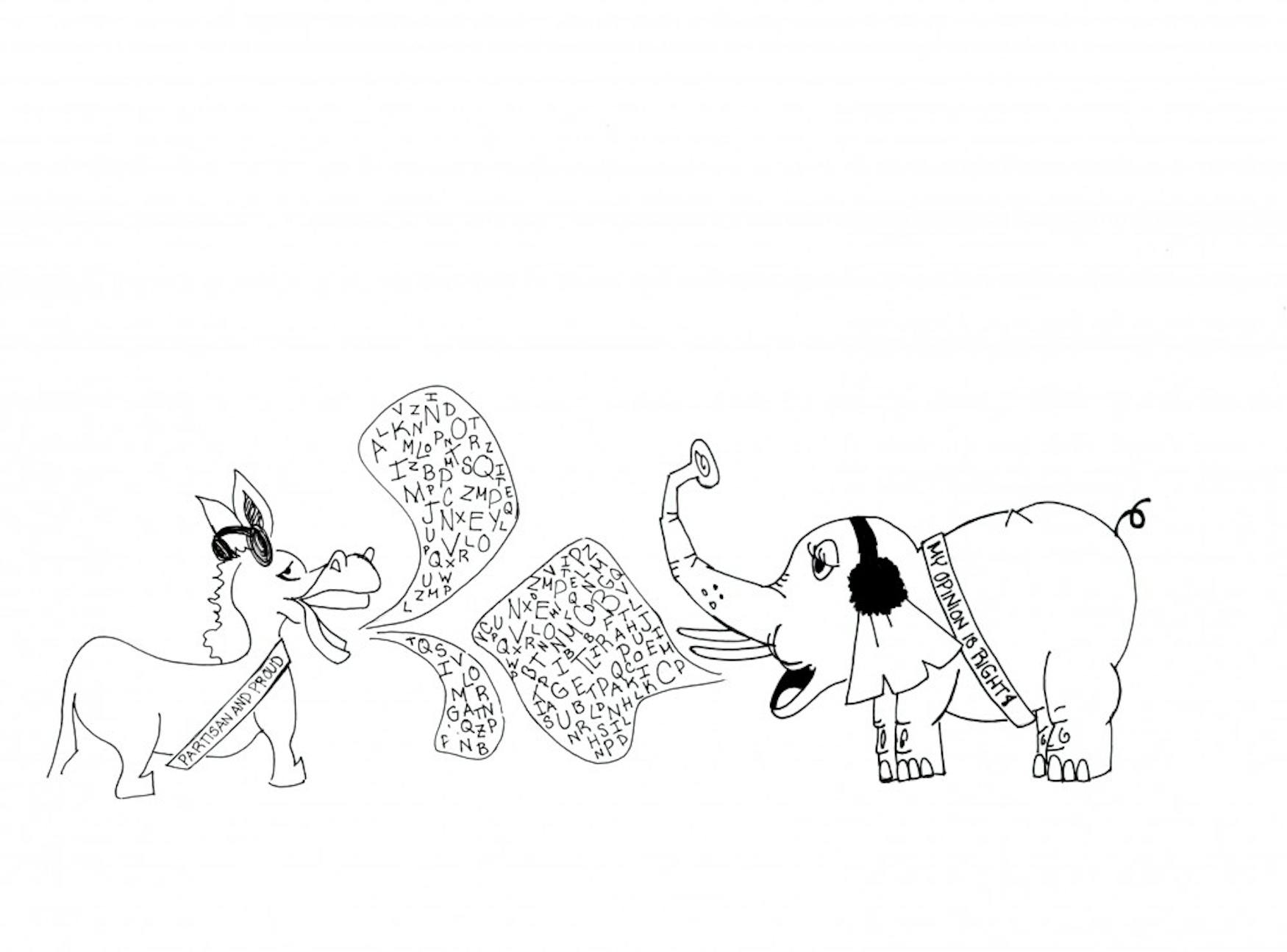

Not only do we not want to be exposed to different viewpoints but it seems that the American people are actively trying not to interact with anyone they disagree with. When we are forced to interact with our enemies, it is not only simple political discourse but a social statement of which in-group we identify with. As Iyengar and Westwood put it, “Political hostility toward the opposition is acceptable, even appropriate… [partisanship] is [both] a political and social divide.”

Partisanship is not, however, something to be proud of nor something to identify with. It is not how American democracy was intended to function and is not a viable way of accurately and adequately addressing the problems of the people. George Washington, the only president to ever be elected who wasn’t a member of a party, famously wrote his farewell address on the dangers of toeing the newly-formed party lines: “It [partisanship] serves always to distract the public councils and enfeeble the public administration. It agitates the community with ill-founded jealousies and false alarms, kindles the animosity of one part against another, [and] foments occasionally riot and insurrection.”

Washington argued that in a country where the people establish their own leaders and where power is derived from the consent of the governed, political parties need more restraint than under any other system. In order for the American experiment to work, he believed that nothing could be allowed to distract government officials from their duty to honor the needs of their electorate. Outside forces are influences that undo democracy.

I would take Washington’s argument one step further. Partisanship itself is undemocratic, but I hold that it is the democratic duty of any citizen to constantly converse with people they disagree with. Refusing even to talk to someone who you brand a political enemy does only a disservice only to yourself—you reduce their argument to a straw man of what it likely truly is, and you reduce their reasoning and opinions to be somehow beneath your own. Opinions are opinions. While some are more nuanced, none are better or worse than others, merely different. In a democracy, the opinion that ends up being the most popular is the one we choose to take action on, and this opinion is usually a composite of multiple sides. The Constitution itself is the result of many compromises, and most everyone can agree that it has worked out pretty well so far.

One cannot make the mistake of assuming one’s views are somehow superior to another’s, just as one cannot make the mistake of confusing political conversation with debate. In formal debate—the kind the Brandeis Academic Debate and Speech Society does—there is a winner and a loser. This formal debate is an exercise and competition in being persuasive. The most persuasive speaker wins. Yet, rarely do BADASS members argue their personal beliefs on the competitive level.

In a conversation, though, there is no panel of judges. Unless a conversation ends with one side dropping to its knees, admitting it was wrong about everything and having a sudden and full change of heart, there is no victor. Conversation and debate are wholly different concepts. A conversation is only an exchange of ideas, an opportunity to better understand someone else’s mindset. Many of the best political conversations I’ve ever had have been with people I vehemently disagree with and whom I’ve never even once won over to fully agree with me. But these conversations tend to end once we’ve argued to a point where we both find some small common ground on which we do agree. We then take things back one step and try to articulate our one essential point of contention and then happily move on to some other conversation. It’s far better to understand what the “other side” thinks as fully as you can then to try and win them over or point to some imagined fatal flaw in their logic which will crumble the whole argument down. Your own opinions become more nuanced after being exposed to someone else’s. You critique yourself to build a better overall opinion, even as you know they are doing the exact same thing.

These conversations are a large part of why democracy works. What is Congress but two big rooms where people argue with each other until they can find something they eventually agree upon? What is an election but an opportunity for lots of people to listen to what a few specific people believe and then state whether or not they agree?

Nowadays, though, partisanship and party systems have forced these conversations away from individual people exchanging individual beliefs and into bloated collectives sparring with each other over votes and donation money. The two major political parties benefit from people being afraid of the other side—in fact, neither could continue at their current size without the other to demonize. And especially in the era of mass media, it is almost impossible to conceive of a way to end partisanship and the massive divides that come with it.

We can, though, at least not feel prejudice and hatred toward those with whom we disagree. We can coexist with each other, and even interact with each other. Refusal to do so would actively uproot that which makes democracy work.

Please note All comments are eligible for publication in The Justice.