Overturn strict voter identification laws at elections

On Oct. 9, the United States Supreme Court issued a rare emergency order to block Wisconsin’s voter identification law for the 2014 midterm election. Because it was an emergency order, the Supreme Court was not required to give rationale. The Wisconsin law, which passed narrowly in 2011, required that voters show some sort of state-issued photo ID in order to vote.

Unlike in states that have passed similar laws, these Wisconsin ID cards were free in theory. In practice, numerous Department of Motor Vehicles workers in Wisconsin reported being fired or harassed for telling residents the cards were free or reminding fellow DMV employees to ask likely voters to request a free ID. Even with the free state ID law, more than 300,000 Wisconsinites lacked valid photo ID.

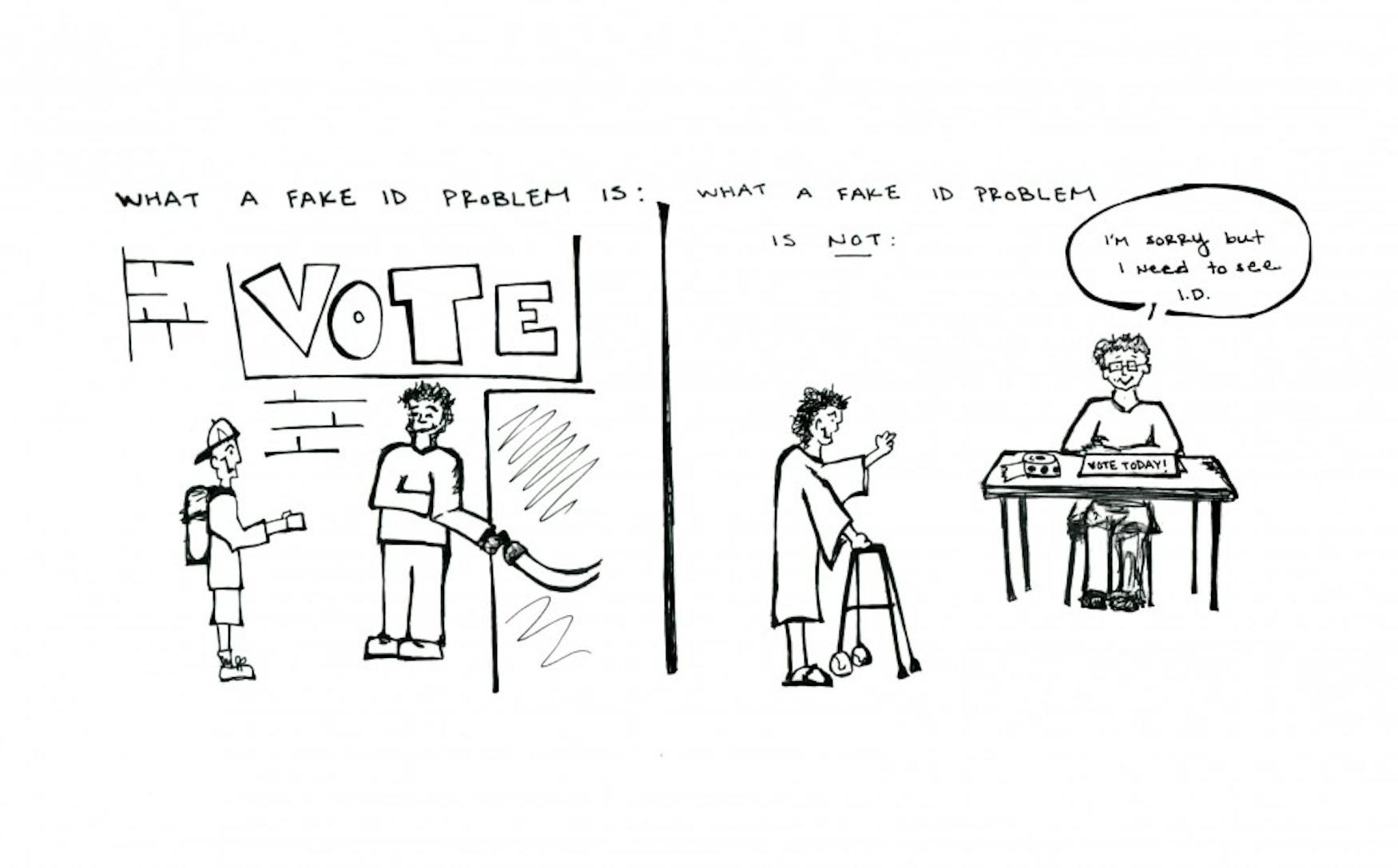

What is the rationale for strict voter ID laws, like the one the Supreme Court just put on hold in Wisconsin? The answer is voter fraud. There is a concern that people who legally cannot vote, such as non-state residents or non-citizens, might go to the polls. One campaign may also “stuff” the ballot box, or someone may vote multiple times in multiple locations on Election Day.

According to a New York Times article, nearly 40 percent of Wisconsin voters believe that over 1,000 votes per election are cast in a fraudulent manner. The fear is not entirely unfounded. This year, a supporter of Wisconsin Governor Scott Walker was charged on 13 counts of attempted election fraud, including attempting to register at multiple addresses for the 2014 gubernatorial race.

This may make it seem like election fraud is a big problem. In fact, it is not. In a study of all American elections from 2000 to August 2014, the Washington Post uncovered a whopping 31 cases of in-person voting fraud that have ever been reported by government officials and poll workers. In-person voting fraud is only fraud that happens at the polls and can reasonably be prevented by a photo ID: someone stealing an identity or using a dead person’s name, for example. To put this in perspective, an estimated one billion votes have been cast since 2000. There have only been 31 cases of in-person fraudulent voting that may have been prevented by stricter voter ID laws. In addition, as the article points out, those 31 cases of in-person voter fraud, at least 18 may have either been caused unintentionally by an uninformed voter or may have only been labeled as election fraud due to clerical error.

Meanwhile, voter registration forms already require one to either put down their state ID number or part of their Social Security number. Even in states like Massachusetts, with more relaxed voter ID laws, one still needs to provide proof of residency, like a college ID or a bank statement. Even without strict voter ID laws, these logical safeguards are in place to prevent fraud.

For the little positive work they do, strict voter ID laws hurt a lot of people, even if the reasoning for such laws may come from a place of well-meaning, but misinformed, concern. Low-income voters, especially people of color, as well as older voters, are unlikely to have the proper photo ID required by many of these laws due to cost concerns or not driving on a regular basis. In 2012, Slate found that between 16 to 25 percent of minority voters do not have drivers licenses, the most common sort of required voter ID. Other would-be voters cannot afford to pay the fees to get a state ID, which can run up to over $100 if certain paperwork is needed. Wisconsin was the only state with strict voter ID laws that had a mechanism for providing free IDs to voters, but voters did not always know they were free.

Another large group that is hurt by voter ID laws is students. Voters aged 18 to 24 make up around 20 percent of the population, but according to Forbes magazine, they only cast about 10 percent of the votes in elections. In 2008, 64 percent of Americans voted in the presidential election, but only 50 percent of youth voters did. Young people are less likely to vote than the elderly for a number of reasons, including concerns that they do not have valid voter ID or that they will get turned away at the polls because they are originally from a state other than the one they reside in currently.

According to a 2012 Huffington Post article, voter turnout dropped nearly nine points among college students who lived in states that enacted voter ID laws. Nearly 20 percent of minority youth, and five percent of white youth, said that concerns over valid ID kept them from voting.

It’s a valid concern. In 2011, over 200 students at universities and colleges in Maine received a letter from the state telling them that they either had to register their vehicles in Maine or not vote in Maine elections. There is no law that says you need to register your car in Maine to vote, especially since Maine’s electoral laws allow out-of-state college students to vote in Maine as long as they have established residence, including within a dorm room, in the state. In the end, after significant controversy, the state allowed the students to vote without registering their cars.

The state said that the letters weren’t intimidation but an attempt to prevent fraud, while students, parents and school officials disagreed and argued that the Republican governor was worried that students would hurt his chances of electoral victory. Even if the state’s actions were well-intended, I cannot help but see this as anything but voter intimidation.

Are voter ID laws intended to make it harder for groups that are more likely to support the Democratic Party, like students, to vote? Or are they passed as an attempt to solve an almost non-existent problem? Are they inherently racist, or are they well-intentioned?

I don’t have an answer. I do have an answer to another question, however: how do we increase the abysmally low voter turnout rate among young people? There are several factors that contribute to low voter turnout, especially among students, but reforming voter ID laws is one of the simplest fixes.

Please note All comments are eligible for publication in The Justice.