Rethink current laws implementing electoral college

The Electoral College could be a lot better than it is.

Many, notably Steven Hill in Fixing Elections: The Failure of America’s Winner-Take-All Politics, have critiqued it, especially in light of elections where the electoral vote disagreed with the popular vote (which has happened four times: 1824, 1876, 1888 and 2000). And many have suggested getting rid of it all together, but few have suggested a feasible revision to it. I would like to propose a painfully simple but effective revision. But first, let’s examine why its current state is an issue.

Each state has the same amount of electoral votes as they have representatives in Congress, with a minimum amount of three (one House representative and two senators). But each state’s electoral votes are not weighted proportionally with that state’s popular vote. Currently, the entire electoral power of a state is determined by the majority popular vote.

Now, let’s break that down. If California were split 51 percent Democrat and 49 percent Republican, currently all of the electoral vote would go to the Democratic party.

Consider that 49 percent of California can also be thought of as approximately 27 electoral votes. The eight smallest states in the United States (including the District of Columbia) only have 24 electoral votes combined. Suppressing half of California’s vote in a given election is worse than not representing the eight smallest states of the United States.

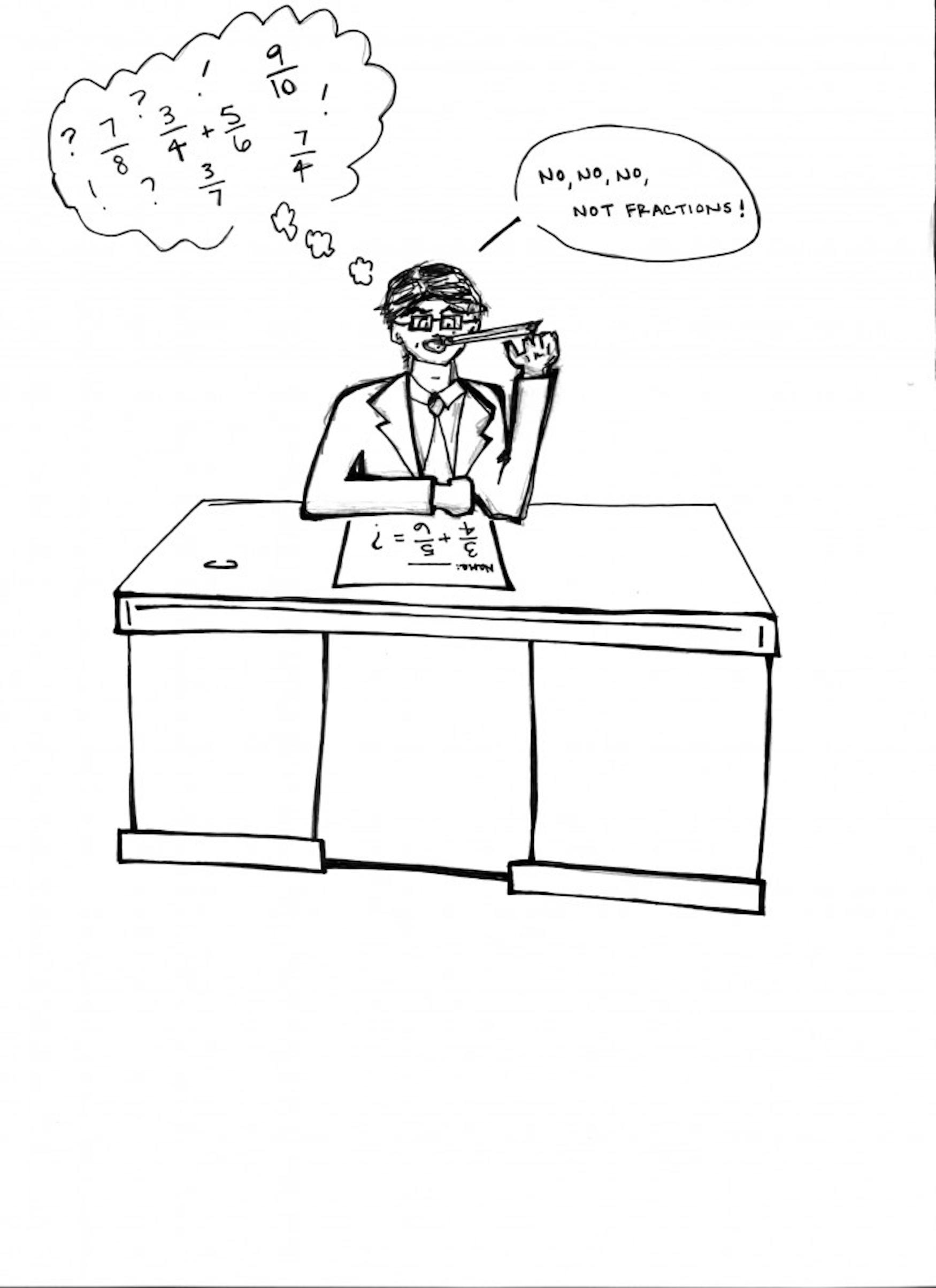

How does that make sense? We knew enough math after 1000 B.C. to handle fractions better than by rounding up. This majority-rule electoral system guarantees that the minority opinion of each and every state is entirely ignored and unrepresented in the presidential election.

The founding fathers created the Electoral College as a democratic compromise between having votes cast by Congress and a pure popular vote to determine the president, but it also had the well-known side effect of giving more of a say to states with lower populations.

Given that majority-rule systems like the current apportioning of all electoral votes to the majority candidate often suppress the wills of minorities (by definition), this seems pretty reasonable.

The solution to the problem is actually remarkably simple and similar to how English parliamentary governments hold elections. Each state should still have the same amount of electoral votes to ensure more even representation from less populated states. But the proportions of the popular vote should decide the electoral votes for each state.

In other words, if California’s popular vote was 51 percent Democrat and 49 percent Republican, then 51 percent of the electoral vote should go Democrat and 49 percent should go Republican. Yes, this means we have to use fractions. No, they’re not scary.

Now that we have our electoral votes directly represented by the popular vote, there’s no need to actually have any physical people who vote in the Electoral College. That notion, too, is antiquated in this day in age. This can be a purely mathematical calculation. Give each side (of our haphazardly dichotomous party representation) the direct proportion of the popular vote it had in electoral votes. Simple.

Now, a viable counter to this approach is that we lose the impression of a presidential candidate “winning a state.” It would no longer be the case that Democrat X had Massachusetts and that Republican Y had Texas. Some might argue that elections where the difference was in fractions of an electoral vote might slow progress because the losing side would not be willing to submit with such close results.

But if Democrat X didn’t have 100 percent of the vote in Massachusetts anyway, Democrat X never had MA to begin with. Democrat X had 70 percent of MA while Republican Y had 30 percent, and that should be represented in the election.

The obvious implication of this is that it destructs the idea of “swing states.” It would no longer be the case that only eight states (in the case of the 2012 election) are important. Each and every state would now matter, and minorities in each given state would feel more adequately represented. Cheers to Republicans in Massachusetts and Democrats in Texas.

It’s worth noting that shifting the focus away from swing states does not at all imply caring less about small states. In 2012, the combined populations of the eight swing states totaled to 18 percent of the U.S. population. The actual eight smallest states sum up to a mere 1.9 percent. The swing states occupy more population than the average and exponentially more than the actual eight smallest states. Therefore, the swing states did not adequately represent smaller populations before, and removing them would not hurt smaller populations.

The Electoral College was developed in order to help smaller states. This idea of swing states actually hurts smaller states, since many smaller states are not swing states. Implementing electoral votes based on proportion would better represent the minority votes of each given state.

Smaller states actually require less campaigning per electoral vote. For instance, in 2013 Wyoming had about 194,000 popular votes per electoral vote whereas California and Texas both had about 690,000 popular votes per electoral vote. This means that presidential candidates have an even stronger incentive to campaign in small states.

Also, as it turns out, the current winner-takes-all system of distributing electoral votes was not even specified in the constitution; it was decided by states, mostly throughout the 19th century. Over two dozen states enforce laws to ensure that electors stay true to the majority popular vote, with some states like North Carolina fining such dissenting “faithless electors” $10,000. This means that no constitutional amendment is necessary for states to veer away from winner-takes-all mechanics—only well-supported state legislature.

The only two states that do not participate in winner-takes-all are Maine and Nebraska, though Maine has never split its electoral vote, and Nebraska only did for the first time in the 2008 election. And neither has split the vote based on the proportion of the popular vote.

There is no reason to suppress the opinion of the minority, either through a pure majority vote or through a broken Electoral College. The solution isn’t some intangible insoluble theory; it’s simple.

It just involves some fractions and a step away from tradition, one (or both) of which have apparently scared off progress for this long.

Please note All comments are eligible for publication in The Justice.