Don’t Try to Solve These Puzzles

Art historian Annie Storr talks about how to look at art and embrace the unknown

Clarification appended.

Looking at art may seem like a simple activity, but Annie Storr, an art historian and educator at at Montserrat College of Art, believes otherwise. During her presentation, Exercises for the Quiet Eye on Nov. 30, Storr asked viewers to reflect patiently on and directly with works of art in an attempt to avoid the premature rush to understand what we see.

EQE is a series of techniques for looking at art or artifacts to obtain a direct, personal experience. There are about 50 exercises that involve looking at a work of art in a different way every few minutes. Some involve drawing and walking around, while others involve singing and standing in place. But all of the exercises are both independent and social, beginning alone and ending in a community.

In practice, EQE is part of the Slow Art Movement, a movement aimed at getting people who look at art to slow down. The average time spent looking at a work of art has increased from 17 seconds to 22 seconds. But in this time, a viewer is merely able to get the name of the work and the artist without establishing an “I/Thou” relationship between themselves and the work of art. The relationship explores a great dichotomy, which is the objectivity-subjectivity split. A phrase that is subjective would be, “I don’t like it,” while something more objective would be, “That picture wasn’t worth painting.” The confusion between subjectivity and objectivity is at the heart of a great deal of the anxiety and frustration that individuals have with art and it’s at the core of discussions in art schools. What EQE tries to do is expand the looking time to more than a few seconds, to a couple of minutes, 20 minutes, or even a few hours. By purposely switching back and forth on the impending solitary moments and shared moments with a work of art, EQE reduces anxiety.

Storr, who is also a visiting scholar at the Women's Studies Research Center, says that there are two major causes for anxiety when we look at art. One is that people are afraid to possibly expose a lack of education. The second cause for anxiety is more simple: that they will mispronounce an artist’s name.

The reason for this anxiety is found on none other than the popular dating website, match.com. One of the best places to go on a first date used to be an art gallery, but in response to the website’s clients, art galleries were taken off their list and put on the list of places not to go on a first date. It was found that looking at art with another person takes a great deal of trust, so much trust, in fact, that it makes us anxious about giving a proper response to a piece of artwork without disclosing our ignorance.

At its core, EQE reduces a viewer’s anxiety by letting go of the gratification for understanding a work of art. Generally, when an authoritative figure or an insightful onlooker says something seemingly cogent on a tour, the entire group comfortably agrees with their interpretation. Storr and other educators always notice when the entire group relaxes because any interpretation is taken as a sign of closure or an easy way of letting the anxiety go. EQE, however, keeps viewers engaged without letting them truly figure out the meaning behind a work of art and giving them the time to discover that the ambiguity of art is one of its strongest facets.

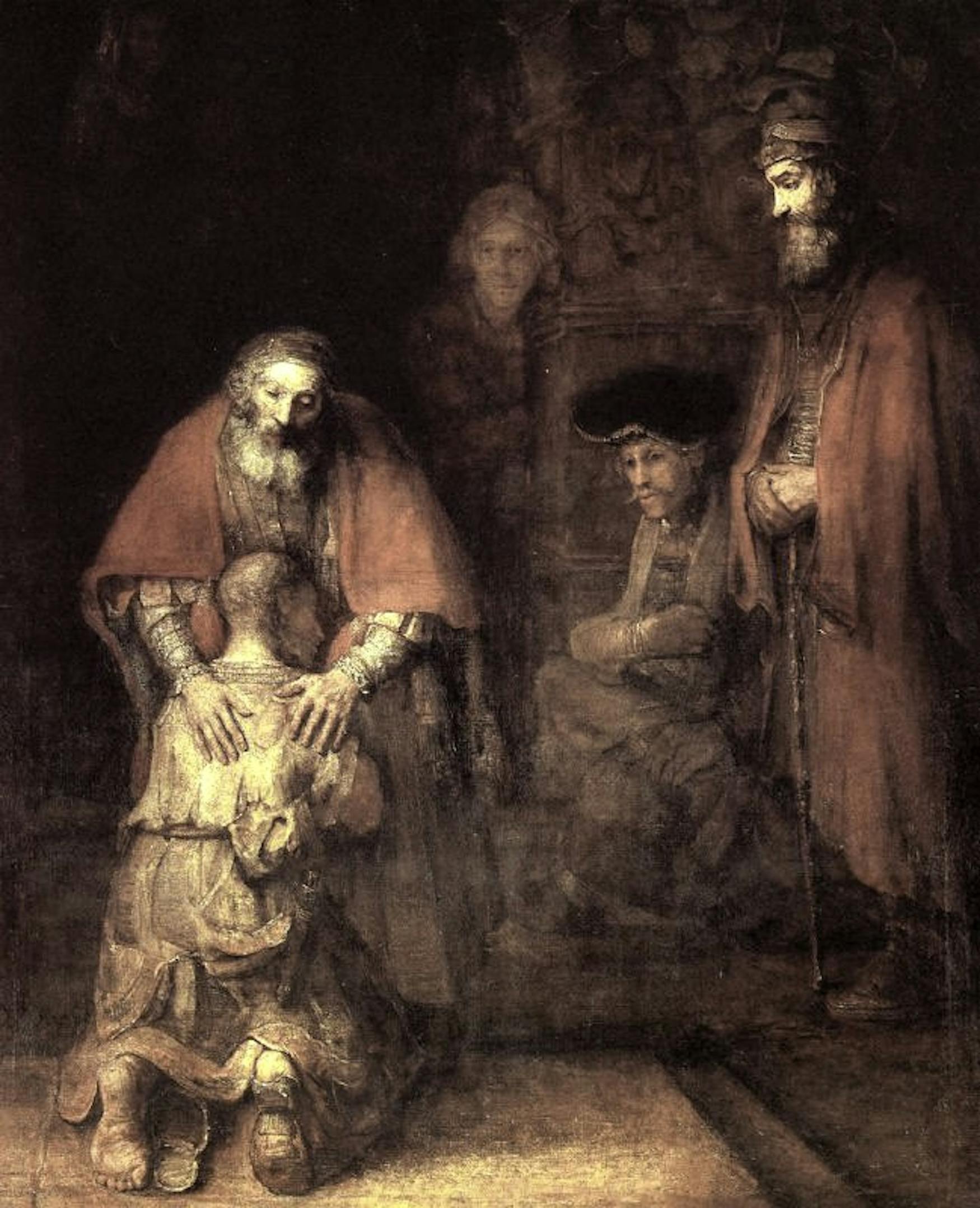

As an art historian and educator, Storr began to talk about her own experiences with art. She believes that teaching is an art form subject to the same creative, reflective, and presentational forms as all art (paintings, sculptures, music, etc.), and that art changes lives. She showed the audience a painting called the Parable of the Prodigal Son. The first time she saw it was on her way sprinting to the European Gallery of the Hermitage Museum. Even with her thirteen-month-old son vomiting in her arms, she forced herself to stop and look. The painting hung low at the head of the long corridor of the museum and was smaller than life size. She immediately noticed how the prodigal son’s neck was green, indicating that he was a corpse, but he wasn’t dead in the story.

About 12 years before, she was in her early twenties, visiting a museum with her boyfriend. She headed up to the modern section that she normally dislikes and sat down on a bench in front of the “Tempest” painted by Oskar Kokoschka. The painting depicts Kokoschka and his wife after sex, and his mind is running with confusion, clarity, and lack of resolution in a moment. She doesn’t remember what she thought of the painting, other than that her boyfriend was somewhere in there, but at that moment, the guards came over and said, “We know you’ve been here [at the museum] every day, but the gallery closed a half hour ago.” That was over two hours since she had arrived. Storr believes that something about the mysteriousness of sexuality touched her early on in life when it mattered most.

What these two experiences have in common is the time frame. The amount of time Storr took to simply look at the paintings without any historical context showed her what it meant to engage and live in the moment. Her confusion with each work of art made her realize that many works of art aren’t meant to be understood. As she said, “I know that art changes lives, so I want to encourage people to bravely look at art because we can’t crack it, we can’t master it, we can’t figure it out and dismiss it.”

This article has been updated to include a clarification that Annie Storr is a visiting scholar at the Women's Studies Research Center.

Please note All comments are eligible for publication in The Justice.