Criticize poor handling of “And Then There Were None”

I went to see “And Then There Were None” last weekend. It opened with 20 minutes of apologizing. The play was fine. The real spectacle came afterwards. Now, I think the play was okay to put on, and I do think that it was appropriate to include in the program. But in the wake of the disaster that was “Buyer Beware” — in which Brandeis took the bait hook, line and sinker — I’m astounded that “And Then There Were None” managed to slip through the cracks. Of the 28 professors the director contacted for advice in March, a pitiful few responded.

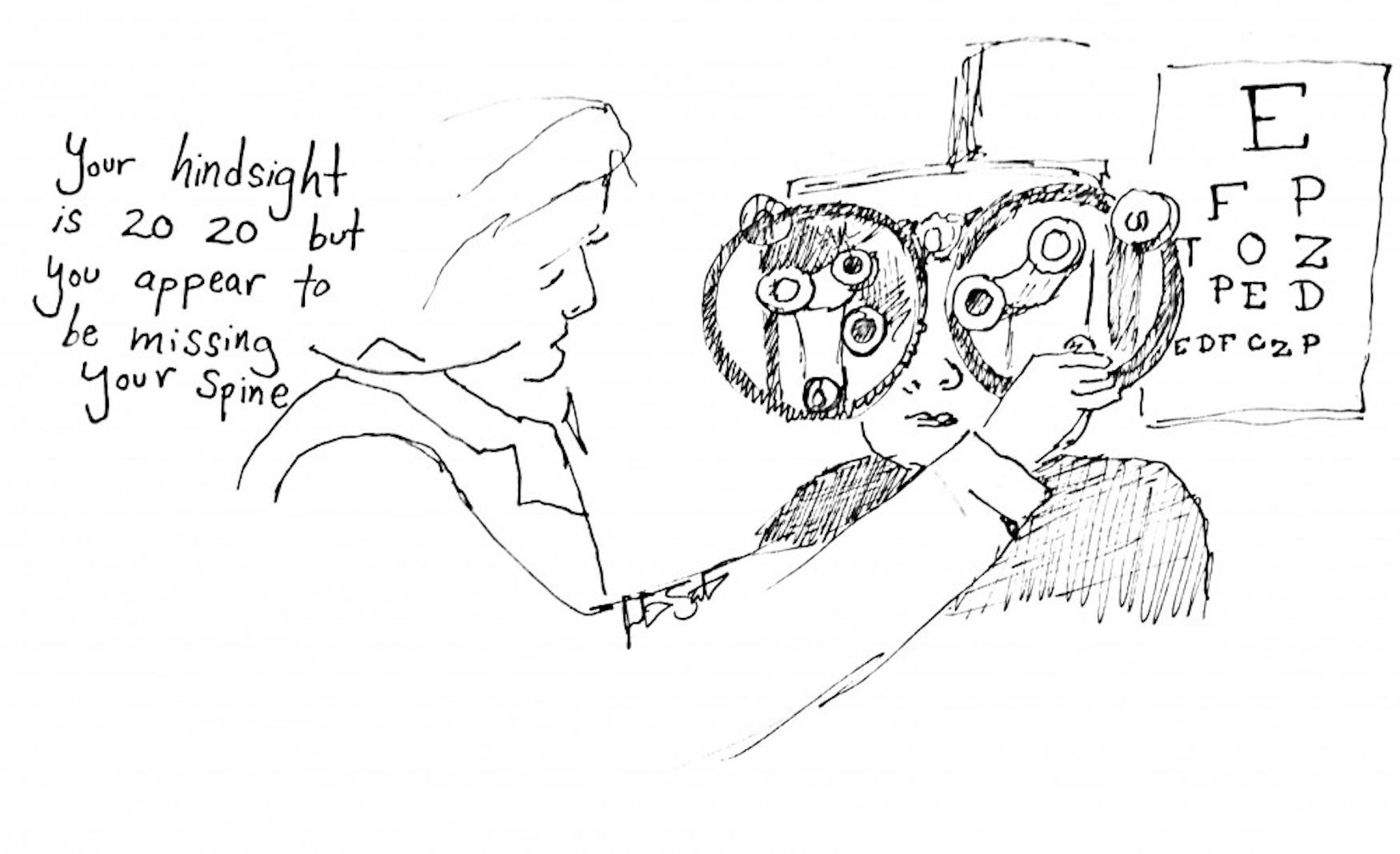

On the day the play was scheduled to debut, seven African and Afro-American Studies professors sent an email urging the cancellation of the play, citing the change in the campus climate precipitated by the firing of basketball coach Brian Meehan. That firing took place a week prior, and yet they waited until the last minute to use their authority to intimidate the students. Let’s call this what it is: bullying. There are many ways to voice concerns, and these professors chose an illiberal one. It was based on intimidation. They opted to shut down dialogue rather than open it — and when a dialogue was opened on Thursday night, none of them chose to attend. Frankly, I expect better from Brandeis professors.

At the Thursday night showing-turned-forum, an overwhelming majority of students in attendance supported putting on the play for its full run. Yet the discussion leaders made a point of stressing that students of color might not have attended because they may have felt unsafe. I don’t mean to discount the way these students feel, but there is a dangerous tendency to conflate emotional and physical violence. “Unsafe” connotes the latter, and to suggest that there was any threat of bodily harm at the panel is simply counterfactual. The conversation was nothing if not polite and respectful. I think the only way to have a productive dialogue is when both sides can come to the table.

The AAAS professors who signed the letter have no excuse for not being at the panel. At the talkback on Saturday night, Prof. Carina Ray (AAAS) claimed that she had originally declined to participate on a panel about the play because she did not want to legitimize the production. This strikes me as particularly disingenuous given her presence at the actual performance and subsequent panel. Given that she called for the play’s cancellation, she should at least be willing to defend that position.

Despite the many students who wanted the show to go on and the no-show professors, the Undergraduate Theater Collective caved to pressure and cancelled all but one of the five scheduled shows. After the remaining show, the actors read agonizing commentaries on the ways in which they reinterpreted their flawed characters. The character Emily Brent, due to her hardcore Protestant beliefs, kicks her pregnant-out-of-wedlock servant to the curb to die. Amy Ollove, who played Brent, stated that she changed Brent’s motivation such that Brent was angry that, in getting pregnant, her servant had assumed a traditional female role rather than living up to her full potential. This dilutes Christie’s message about the dangers of religious fundamentalism, and adds what exactly? A message that progressives can be terrible people too? Ollove emphasized that the Bible itself was not flawed, only Brent’s interpretation of it. Oh, the hypocrisy of being outraged at Agatha Christie while defending the Bible! I don’t understand why a villainous character who gets her just desserts can’t be portrayed as such.

I have similar concerns about Lombard, a racist and sexist character whose line revealing the depths of his racism was cut from the play. Christie’s commentary is that Lombard’s bigoted attitudes are his undoing, an analysis so cursory that it can be found on SparkNotes. Not to mention that the point of theater, as all good art, is to provoke the audience to feel something. If you truly hate Lombard, it makes his comeuppance so much sweeter. When I raised this objection, white actress Alina Sipp-Alpers ‘21 blindsided me with her response that she and her cast members wanted to make white people uncomfortable, not Black people. How incredibly patronizing! To deem yourself the arbiter of what is and isn’t safe for Black students is to imply that they can’t make that choice for themselves.

Judge Wargrave, the murderer who seeks justice for crimes left unpunished in the legal system, was accused of being a white supremacist by actress Blake Rosen ‘20, who portrayed the judge. The only textual evidence for this was from the judge’s use of the originally racist rhyme. The cast seemed to think that Christie’s replacement of the poem’s final line with “he went out and hanged himself, and then there were none” was a veiled reference to lynching, a practice which was far less common in England than in the American South. Lost on them was the symbolism that Wargrave was a “hanging judge” – implying that the punishment did not fit the crime and that Wargrave, too, was a villain in this story. If Wargrave was a white supremacist, why seek justice for the 21 Africans killed by Lombard?

Alina Sipp-Alpers, who played Vera Claythorne, suggested that her character gained agency by choosing to shoot herself at the end of the play. In the novel, Vera does kill herself, which is a reason I like the novel better than the adaptations for film and stage. Overall, I think returning to the original ending is a good choice. But that’s not what happened. In the novel, Vera hangs herself with a noose provided by Wargrave. She does so because of her fractured mental state and her obsession with completing the rhyme. In no way can this be called taking agency. The way the play was staged, Vera had the opportunity to kill Wargrave but chose to “take agency” and kill herself instead. The idea that suicide can be a form of taking agency is as harmful as it is insensitive. On top of that, I resent the idea that the cast knew better than one of the greatest writers of all time how the story should end.

As anyone could have guessed, the discussion after the play was nothing short of a trainwreck. The cast’s parents and grandparents, who were rightfully indignant, recieved no good answers. Professor Ray claimed that if the rhyme had been about Jews, “We wouldn’t be sitting here” – and then evaded an attempt to get her to clarify that statement. She also responded to my criticism of the email she sent to the cast on behalf of AAAS with “I have a right to free speech too” – an argument on a par with “it’s a free country!” I left the theater deeply troubled about the future of Brandeis.

Students should be able to decide what art is and isn’t suitable for them. They should engage in liberal protest, such as turning away from the stage, holding signs outside or – here’s an idea – not going to a play when they find it to be unsuitable. Twice in quick succession have students and most alarmingly faculty, deemed art unsafe for other students. We have set a dangerous precedent. In so doing, we are playing into the right’s narrative about colleges. Universities have always been the bastion of free speech, as has the left – and we are letting it be snatched from right under our noses.

Please note All comments are eligible for publication in The Justice.