U.S. and China lurching ever closer to full-blown trade war

While the president and the students are all trying to survive the midterms, the ongoing trade war between China and the United States has just added a touch of pessimism to the national outlook. On Sept. 24, $200 billion worth of United States tariffs on Chinese aircrafts, textiles and computers took effect, and the Chinese reaction was $60 billion worth of tariffs of their own in retaliation.

It seems that the trend toward economic globalization in the last century has begun to fall apart. An Oct. 19 CNN article states that China’s Gross Domestic Product growth rate has been falling because of the trade war. This is partially true. The trade war is just one of the reasons to account for China’s falling rates. According to the Federal Reserve, the GDP growth rate of China has been falling annually from 10.6 percent in the early 2010s to 6.9 percent in 2018. The rising pressure on low-cost exports, despite risking the stock markets in China and the U.S is pushing the Chinese economy toward being increasingly internalized. In the Western Hemisphere, the U.S. is also attempting to revive domestic production, trying to quiet discontent among working classes by creating this notion of “external threat” from foreign countries. Both superpowers show signs of internalizing their economic activities, from primary agriculture to manufactured products.

Economic globalization has rapidly accelerated since the 1980s. In 1979, Paramount Leader Deng Xiaoping opened up the Chinese market for U.S. investors. Suddenly, tens of thousands of Chinese students were sent to the U.S. to study, and U.S. firms built factories and exported products to China. The following 30 years were crucial for China’s development. Low-cost production strengthened the economic dependence between the U.S. and China.

Now, the two superpowers have begun to shatter the dependent relationship with one another, reverting into domestic purchasing power and manufacturing. Uncertainty in China centerss on whether the country’s firms will march into a more competitive market or perceive this free market as stagnating the potential for economic growth. For the U.S., the short-term uncertainty rests on the midterm election, which might change the domestic fiscal policies and game theory strategies toward other economies.

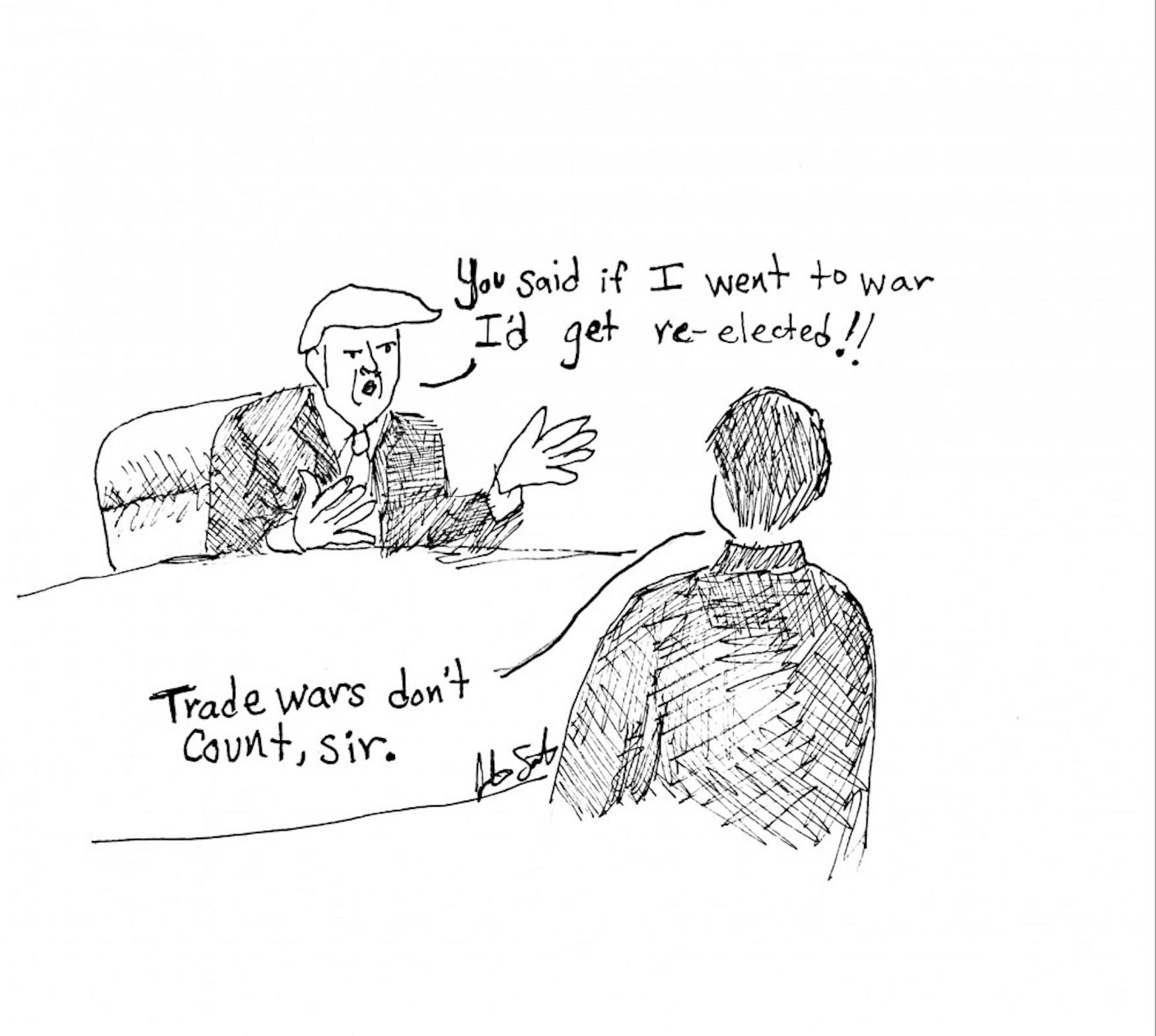

Aggressive nationalism will likely stagnate long-term economic development. This kind of nationalism is surging in both countries, to the extent that it has reduced the necessary understanding, knowledge and even consensus among huge economic powers. “The Chinese have lived too well for too long,” said President Trump at an Oct. 11 rally. This statement would be perfect if it accounted for the two-century internal and external struggle that took place in China, where many people were only lifted out of extreme poverty some 30 years ago. For the U.S., targeting China would be a good thing: A universal enemy could present a distraction for the suffering working class, and could boost domestic production and gradually reduce reliance on the low-cost Chinese products. The Chinese economy is also prepared to stimulate domestic demand and reduce its reliance on U.S. imports by lowering interest rates by 1 percent in July, and reducing non-U.S. import tariffs.

The question is: how can the U.S. and China minimize costs from their trade war? Developed countries used to minimize costs by producing in developing countries and maximize gains from trade by comparative advantages. To reduce the negative impacts from a trade war, something that can surpass these notions must emerge — such as technical advances in artificial intelligence and high-tech machineries to reduce labor costs that once incentivized firms to produce in other low-cost developing countries. U.S. withdrawal from the Trans-Pacific Partnership Agreement could be signaling an intention of forming new cross-Atlantic trade agreements excluding China.

Under globalization, the rising national debts of many nations pose uncertainty to creditors and debtor nations alike. In the future, we may observe greater fiscal deficits. The trade deficit of goods and services between China and the U.S. has risen by $7.476 billion since May 2018. Since the government responded by providing a surplus to farmers that suffered from the tariffs, the fiscal deficit may continue to grow. Since the Federal Reserve raised interest rates by 0.25 percent last month, bonds have been more competitive as substitutes for stocks. U.S. investors should expect more upcoming volatility on the stock market. Some good news for U.S. industries comes in the form of booming consumer confidence in the third quarter of 2018. The S&P 500 Index of U.S. stock market had gone up by 1.3 percent in September. This economic upturn is traceable, particularly in higher demand for the auto-sale businesses and used cars.

This divisive effect of globalization also appears in China, as Beijing responded to the latest trade tariffs by lowering interest rates and trade tariffs on non-U.S. goods. The first possible trait that correlates to a more development-based economy is the decreasing rates of low-income migrant populations moving inside China. These rates have been dropping since 2014, indicating greater urbanization and more developed infrastructure. More people would like to settle down instead of moving toward larger cities. Major cities are overburdened. Less major cities like Shijiazhuang, Changsha, and Hangzhou are saturated. A second factor at play is the country’s aging population and low birth rates.

Children younger than 15 are becoming a smaller portion of the total population, yet the population of elderly people aged 65+ is growing, reaching 11.4 percent by 2017. Last but not least, economic profits for the new entrants fall as the market becomes more competitive in these industries. Per the data released by Zhongtai Securities Institute, the median of the change in profit margin for Chinese manufacturing industries was 1.1 percent in the last eight years, compared to 3.7 percent from 2000 to 2010.

The trade war has just begun; the previous Japan vs. U.S. trade war lasted two decades in 1960s-1980s. Will the mutual dependence between the U.S. and China be torn up? Well, the internalization of economic activities can go either direction. The goals that the two superpowers may pursue are to form new regional trade areas, and to optimize their own economic systems so as to boost domestic innovation and suppress bubbles in stock and real estate markets.

Please note All comments are eligible for publication in The Justice.