Leonard Bernstein: Beyond Music

An exhibition on Bernstein highlights the musician’s affair with controversy

Leonard Bernstein graduated from Harvard University in 1939 in an unusual fashion — with a diploma and the beginnings of a 600-page FBI file detailing his political activities. The aspiring conductor was unaware of the dossier for some time.

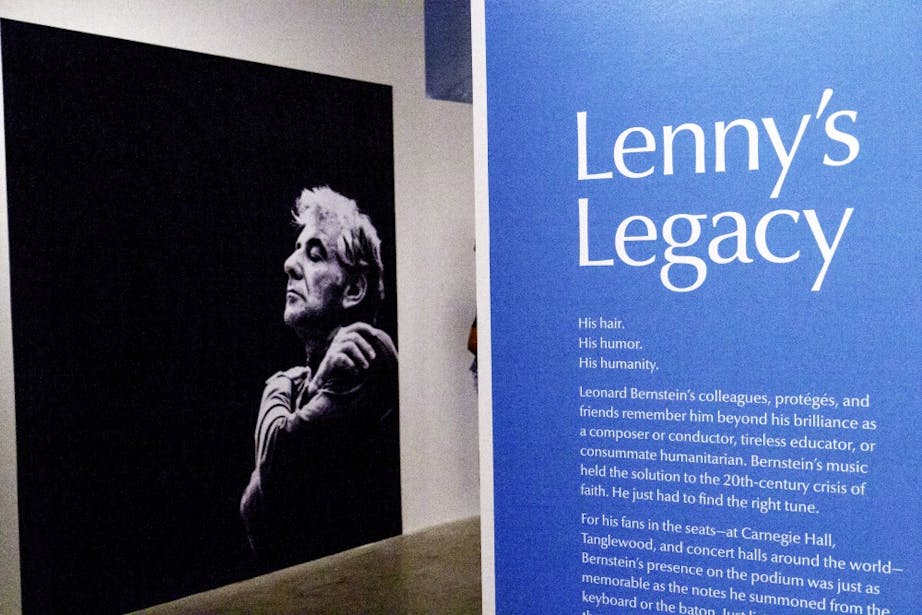

In an exhibition organized by The National Museum of American Jewish History titled “The Power of Music” on display in the Spingold Theater Center through Nov. 20th, Bernstein’s life’s work is chronicled for the public to see. The FBI file on Bernstein has been put in a binder for visitors to peruse, but many in attendance turned their gaze elsewhere — to the monitors and portraits on the walls of Bernstein conducting the New York Philharmonic and the letters in display cases that the composer wrote throughout his career.

THE BRANDEIS YEARS: Despite his short tenure at the University, Bernstein was a beloved teacher who made a profound impact on campus.

In an essay titled “Leonard Bernstein and the FBI,” provided to the Justice last spring, Prof. Steven Whitfield (AMST) examines Bernstein’s affair with controversy and how, if events had unfolded differently, the binder of FBI documents in the exhibit could have easily ruined his career. Whitfield writes, “This swollen dossier suggests the risks that he took (perhaps unwittingly) by signing the numerous progressive petitions that circulated in the cosmopolitan cultural circles he inhabited.” Bernstein was one of many prominent figures targeted by the Red Scare, and because of his place on the FBI security index, he could have been arrested and placed in a detention camp in the case of a national emergency. Whitefield notes that the Truman administration even revoked Bernstein’s passport and pressured CBS to blacklist him from their airwaves for four years during the 1950s in an effort to intimidate the rising star, whom the state department considered to be a communist sympathizer.

While FBI investigations hindered Bernstein early on, success for the young composer was imminent. A sign at the exhibition notes that at the age of 25, “On a few hours’ sleep and a lot of nerves, Bernstein took a leap of faith and stepped onto the podium at Carnegie Hall, and guided the orchestra through Don Quixote. His debut was broadcast nationally to rousing success: It made the front pages of the New York Times and catapulted the boy wonder to stardom.”

By 1954, a series of successful appearances on CBS’s “Omnibus” and his original score for the major motion picture “On the Waterfront” helped establish the young and telegenic musician as what Whitfield calls “the most influential of all educators into the mysteries of classical or ‘serious’ music.” Soon, that success brought Bernstein to the University in the summer of 1951 as one of Brandeis’ first 71 faculty members. Although his short tenure at the University ended in 1953, he made a lasting impact on the students and the Brandeis community, as evidenced by the annual festival of arts named after and dedicated to him.

The exhibition sheds light on a central theme in Bernstein’s life and career: a crisis of faith. One of the exhibit walls reads, “World war, the Holocaust, the Civil Rights movement, nuclear weapons — all tested Bernstein’s faith.” More often than not, Bernstein’s approach to music and his personal opinions were intertwined, as he was political in every sense of the word, vocally supporting the Civil Rights movement, marching in Selma, Alabama, fundraising for the Black Panthers, and vehemently opposing the Vietnam War. A day after the assassination of President John F. Kennedy, he conducted the first televised performance of Mahler’s “Resurrection Symphony.” Addressing the audience afterwards, Bernstein famously said, “We musicians, like everyone else, are numb with sorrow at this murder and with rage at the senselessness of the crime. But this sorrow and rage will not inflame us to seek retribution; rather, they will inflame our art. … This will be our response to violence: to make music more intensely, more beautifully, more devotedly than ever before.”

FBI REPORT: Bernstein’s political activism made him a target of the Red Scare. An FBI investigation, including a 600-hundred page dossier on him came close to ruining Bernstein’s career.

Over his long career, Bernstein served as the music director for the New York Philharmonic for 11 seasons, composed three symphonies and wrote the music for “West Side Story,” “Peter Pan,” “Candide,” “Wonderful Town,” “On the Waterfront” and “Mass.” He educated a generation of Americans on the capacity for music to effect change both on the Brandeis campus and through his CBS television series, “Young People’s Concerts.”

As visitors made their way through the exhibition, Cynthia McKee, a Waltham local, stopped to sit at a desk piled with envelopes and blank sheets of paper. She grabbed a pen and wrote a letter to Bernstein. Before leaving, she shook her head and told the Justice, “We need a Bernstein today, we need somebody who believes in the power of music and the arts.”

Please note All comments are eligible for publication in The Justice.