Activists misunderstand the groups they’re fighting for

Present-day sociologists and internet activists are socio-economically divorced from the groups whose rights they claim to champion. Today, a lot of protests and activist movements are led by the Internet and privileged college graduates who use terms like ‘agency’ and ‘equity’, words that their professors and peers understand, but alas, not those minorities whose rights they fight for.

A lot of sociological scholarship is bleeding into the mainstream culture, and contemporary activists are using academic jargon to fight vague and ill-defined antagonists. An example of one of their popular terms is ‘White-Savior Complex.’ What is ironic here is how their term describes their relationship with the minorities they purportedly advocate for. African-American journalist and writer Ta-Nehisi Coates has extended the term to ‘White-Savior Industrial Complex.’ He reasons that these activists, with the use of abstract language and sociological and linguistic theories, aren’t giving due diligence to the people they are fighting for. They aren’t acknowledging how the minority groups they’re advocating for often don’t have the ‘privilege’ to comprehend, let alone join their protests.

Peggy McIntosh, a women’s studies scholar at Wellesley College, coined the term ‘privilege.’ Privilege, the idea that some people benefit from unearned and largely unacknowledged benefits, is an idea that has definitely permeated popular consciousness.

It was one of McIntosh’s principal ideas in her treatise ‘White and Male Privilege: A Personal Account of Coming to See Correspondences Through Work In Women’s Studies.’ The beauty of McIntosh’s work is how it presents a very complex and abstract sociological theory with language that even high school and college students can comprehend. The same noble intent is apparent in Charles Darwin’s 1859 work ‘The Origin of Species by the Means of Natural Selection.’ Darwin and McIntosh are specimens of ‘privileged’ writers whose works, despite their density and complexity, seek to communicate to an audience as wide as possible.

The idea for McIntosh, in particular, is to let people attest to their own personal

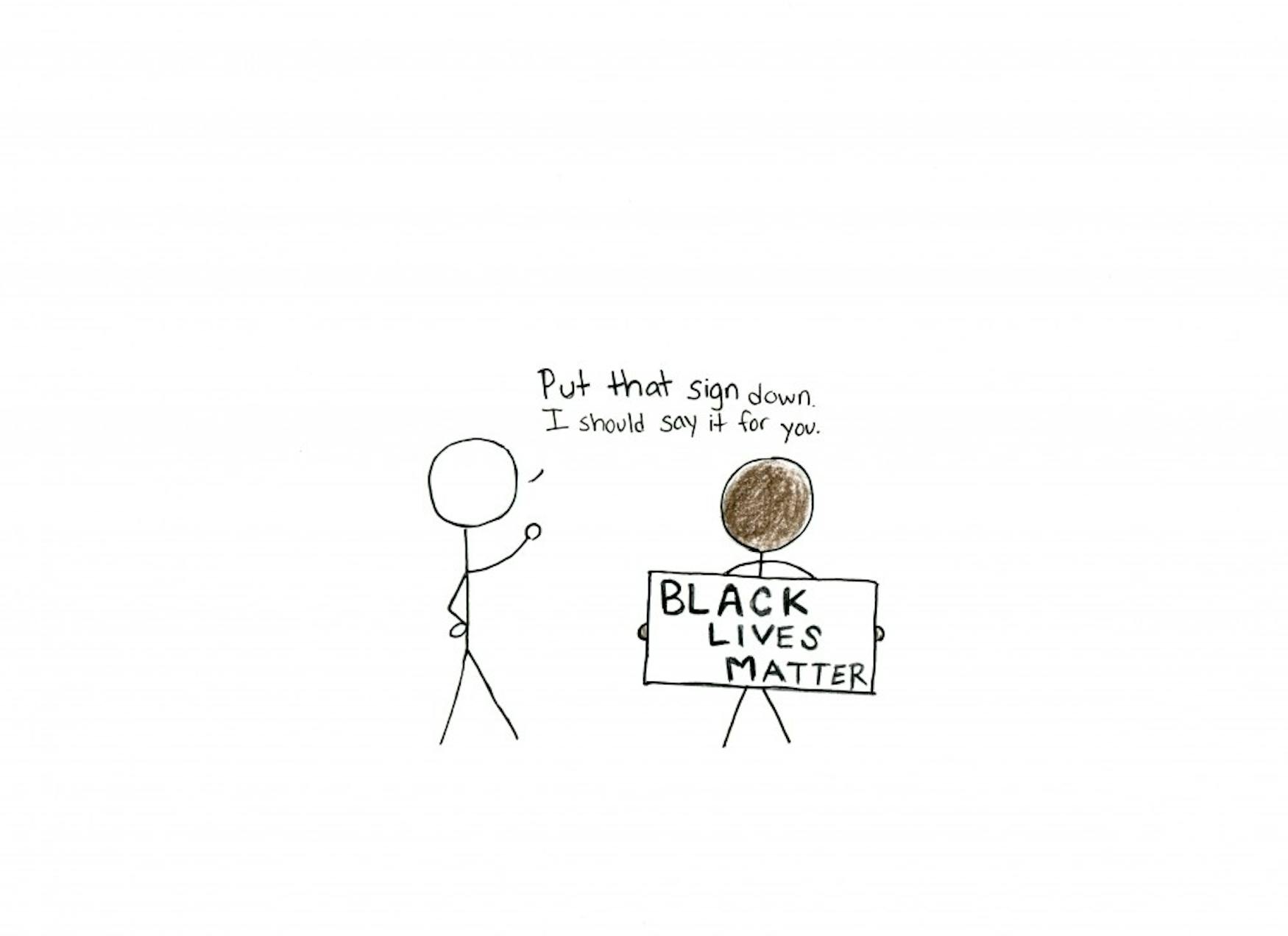

experiences. She quotes Adrienne Rich, a National Book Award-winning poet, the beginning of women’s studies, ‘Nobody told us we had to study our lives, [or] make our lives our study.’ McIntosh reads Reich’s line as a call to empowering minority groups. Her ultimate vision is for minorities to hold up their own protest banners. She wants minorities like African-Americans to be conscious and critical of the widespread effects of America’s history of slavery and segregation. McIntosh, in a 2014 New Yorker interview with Joshua Rothman, speaks of personal testimony as the greatest form of protest. “The key thing is to let people testify to their own experience. Then they’ll stop fighting with each other,” she notes. Here, her argument is that conflicting sides share their sides of the story with each other. A lot of emphasis is put on the phrase ‘testify to your own experience.’ McIntosh is asking everybody to reflect and relate how oppressive systems have affected their lives. This idea highlights a key element missing from today’s protests: the importance of the voices of those we are fighting for.

It is, therefore, condescending that some activists insist on speaking on behalf of minorities. Their reasoning is that minorities often feel ‘unsafe’ or ‘threatened’, and thus it is the activists’ prerogative as the ‘privileged’ to speak up for those who cannot. This rationale rests on a very problematic assumption: That minority groups are so paralyzed by fear they can’t speak for themselves. History teaches us otherwise. We need not look further than Boston’s old shipyards to recall the Boston Tea Party of 1773. The colonists were oppressed by the British Crown, and were asked to pay exorbitant taxes to a government that represented their needs poorly. The demonstrators took matters into their own hands and wrecked one of the British East India Company’s ships, bringing about the American Revolution, the United States’ successful bout for independence.

In March 2017, National Book Award-winning novelist Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie

garnered much criticism from contemporary activists for her comments on the nature of a transgender woman’s experience of gender. In her reply to the backlash, she stated that the real reason why the public was outraged over her statement was because she hadn’t used the vocabulary that contemporary activists insist be used in these dialogues about race, gender, and sexuality. “Had I said, ‘a cis woman is a cis woman, and a trans woman is a trans woman’, I don’t think I would get all the crap that I’m getting, but that’s actually really what I was saying. “But because ‘cis’ is not a part of my vocabulary – it just isn’t – it really becomes about language and the reason I find that troubling is to insist that you have to speak in a certain way and use certain expressions, otherwise we cannot have a conversation, can close up debate. And if we can’t have conversations, we can’t have progress.”

The ‘language-orthodoxy’ that has gripped America’s left is based on the Sapir-Whorf

theory, a theory developed by German anthropologists Edward Sapir and Benjamin Whorf. They held the belief that the structure of a language affects its speaker’s worldview. Simply put: language determines thought. Therefore, contemporary activists reason that changing the way we speak about race, gender, and sexuality will ultimately change for the better; especially in regard to how these topics are conceived. But this theory comes with a lot of shortfalls. Firstly, Sapir and Whorf never did actually propose their hypothesis to the linguistics community. Decades later, in the late 1980s, a new school of linguists extensively examined the Sapir-Whorf theory. The bulk of their findings indicated that language does influence some, but not all thought. Another reason to dismantle Liberal Speak is that it is a very pernicious form of fascism. It forces people to hold certain opinions which they may not entirely agree with. Liberal Speak narrows human vocabulary by offering a set of approved words that citizens can only use: ‘visually impaired’ instead of ‘blind,’ ‘vertically challenged’ instead of ‘short,’ ‘person of color’ instead of ‘black.’ The intention is indeed a noble one, as it seeks to address history’s wrongs. However, wiping away the complete derogatory context of words that are used so ubiquitously may not be an effective way of resolving history’s traumas and wrongs.

We should look to the 1960s Civil Rights Movement as inspiration for how to better

conduct protests. Ordinary citizens, such as Rosa Parks of the Montgomery Bus Boycott, made the world conscious of America’s segregationist policies through action, not through esoteric theories. Leaders as accomplished and intelligent as Martin Luther King Jr. knew this. The ‘I Have A Dream’ speech is a paragon of what minorities can achieve should they receive the platform to advocate for themselves. Dr. King’s speech still resonates today. His prose is simple but retains its emotional power. Contemporary activists should study Dr. King’s ‘I Have A Dream’ speech, and they should note that it is interested in neither sociological theories nor abstruse academic jargon. Moreover, they should note that it puts the people it is advocating for at the forefront.

Please note All comments are eligible for publication in The Justice.