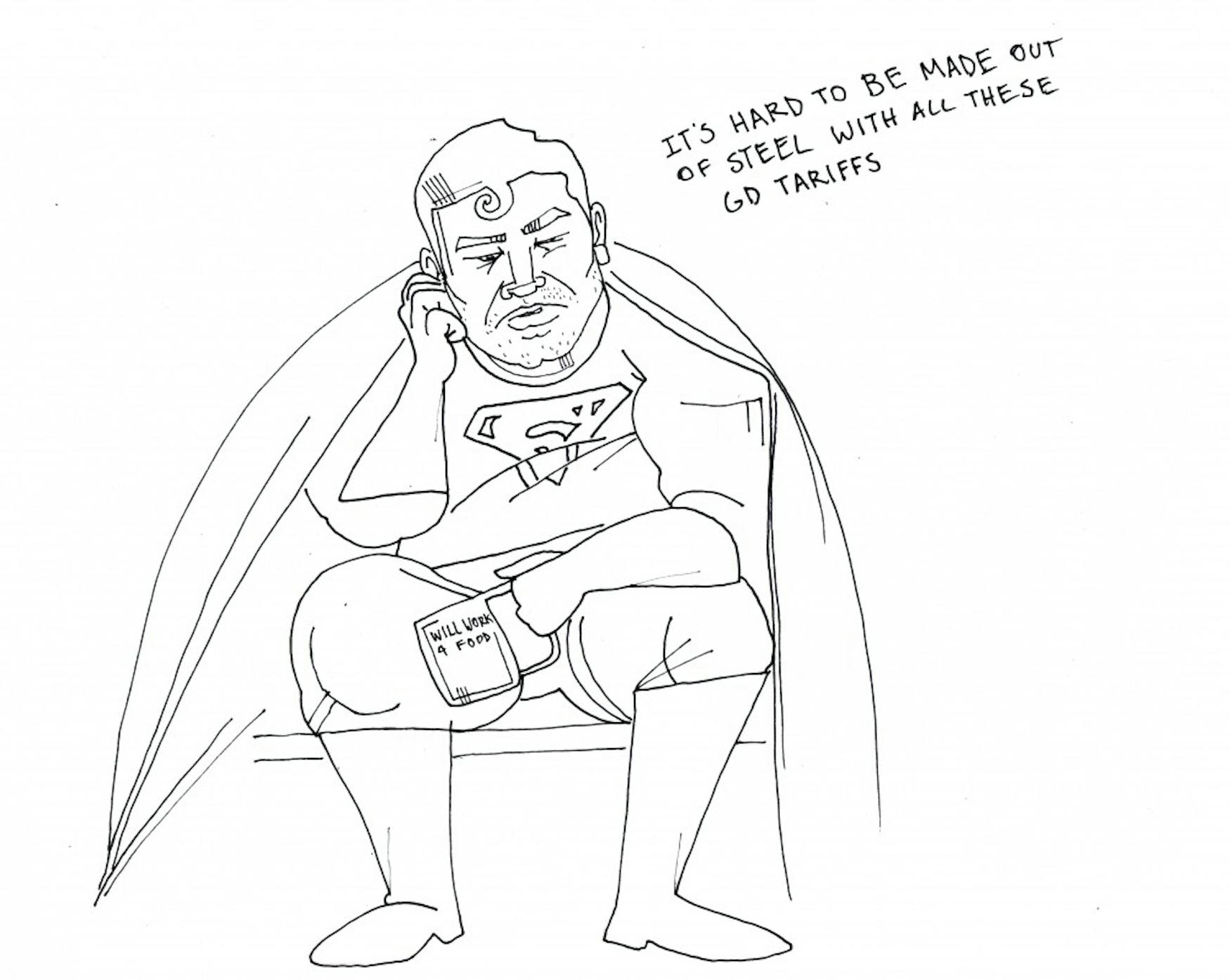

Trump's steel tariffs do more harm than good to U.S. companies

Trade and the economy were two of the major cornerstones of Donald Trump’s presidential campaign. In an appeal to voters of the rust belt states, many of which also happen to be swing states, Trump asserted that he would fix the “disastrous” trade deals imposed by the previous administration in a bid to bring back manufacturing jobs that were outsourced overseas. The main way Trump plans to fix these trade deals is through tariffs. A tariff is a tax on an imported good, and a 15-percent tariff, for example, would indicate that for every dollar of that good a company buys, the company would have to pay the United States government 15 cents. The effect of this tariff is a higher price for the good for both consumers and producers alike, as producers inexorably due to an increase in manufacturing costs. After less than two years into his first term in office, one of the products that Trump has implemented tariffs on is steel. This has produced a wide range of reactions from across the political spectrum. Unsurprisingly, Trump has doubled down and defended his policies even as some of his top economic advisors, such as former National Security Advisor Gary Cohn, have resigned in opposition. In reaction to these new tariffs, there have been those who argue that Trump’s policies hurt the economy more than they help it, but there have been others who have supported them, most notably the domestic manufacturers of these items. A survey of leading economists from the Initiative of Global Markets indicated that although the tariffs would benefit some companies, the net economic losses as a result would outweigh the net economic gains. The organizations who would benefit from these tariffs are the domestic producers of these products, while the companies that would be undermined are those that utilize these raw materials for their manufacturing plants that in turn would be hurt by the rising costs.

U.S. tariffs on steel and other goods are not without precedent. In 2002, then-President George W. Bush imposed a 30-percent tariff on steel imports in an attempt to protect the U.S. steel industry against rising imports. When some of us think of steel, we may only see it in terms of its effects on major automobile and machinery manufacturers such as Ford, Caterpillar, Chrysler, Boeing or General Motors. However, steel is a crucial part of an eclectic range of business, ranging from tire manufacturers to petroleum refiners, and according to the U.S. tax foundation, 98 percent of all steel-consuming sectors in the U.S. employ less than 500 workers. This would mean that an increase in steel prices would have a deleterious effect on small firms that have very little market power to influence prices in the grand scheme of the economy. Because of this, the tax foundation claims that larger steel prices would lead to a loss of 200,000 jobs in the steel-consuming sector, compared to the 187,500 total employees in the steel-producing sector at the time. However, a March 2018 Bloomberg article points out that although GDP, or total national output, may have gone down during that period of time, U.S. steel prices have increased, helping domestic steel producers. Conversely, a study by the Peterson Institute of Economics points out that the tariffs increased employment in the steel sector by 3,500 workers, although this is small in comparison to the jobs that were lost. In simpler terms, U.S. Senator Lamar Alexander (R-Tenn.) claimed that “there were 10 times as many people in steel-using industries as there were in steel-producing industries.” Threats of retaliatory tariffs and the lack of clear benefits forced the Bush administration to renounce the tariffs after 18 months, despite the fact that Bush himself originally planned to have them implemented for a period of at least three years.

Now, President Trump finds himself in a situation similar to that of Bush, but the overall economy and steel industry is very different today than it was in 2002. In 2002, China produced about 200 million tons of steel, but today that number sits at 800 million. Simulations and predictions also reveal that the results of Trump’s tariffs would be similar to those in the past. The Trade Partnership, an international trade and consulting firm, predicted that the proposed 25-percent steel tariffs Trump would impose would increase U.S. iron and steel manufacturing employment by 33,000 jobs, but cost about 180,000 jobs throughout the whole sector, leading to a net loss of about 150,000 jobs. The Trade Partnership’s numbers do not take into account any potential retaliatory measures that may be imposed on the U.S. by other countries.

The study, however, does take into account the jobs lost from consumer spending as the effects of price increases lower the monetary powers of consumers and reduce consumer spending in goods and appliances that are made out of steel, such as washing machines and cars. Therefore, one should not only look at the direct effects of these tariffs, but also at the cascading effects these tariffs would ultimately cause. The bottom line is that the effects of steel tariffs on the economy are pernicious and not beneficial. It is easy to point out the effects of a tariff when a major corporation shuts down a plant or announces layoffs. We saw this a few months ago when General Motors announced the removal of workers in its plants in the United States and Canada. It only took a couple of days for President Trump and Prime Minister Trudeau of Canada to voice their displeasure on Twitter, and the incident became a major talking point for the major news outlets and economists.

Some supporters of the Tariffs may point to a new production plant opening up, or an increase in sales at one given site, and it can be an appeal to voters and to those in industry who have been affected by foreign competition. However, as was the case during the Bush administration, the net effect of these steel tariffs would do more harm than good to the economy.

Please note All comments are eligible for publication in The Justice.