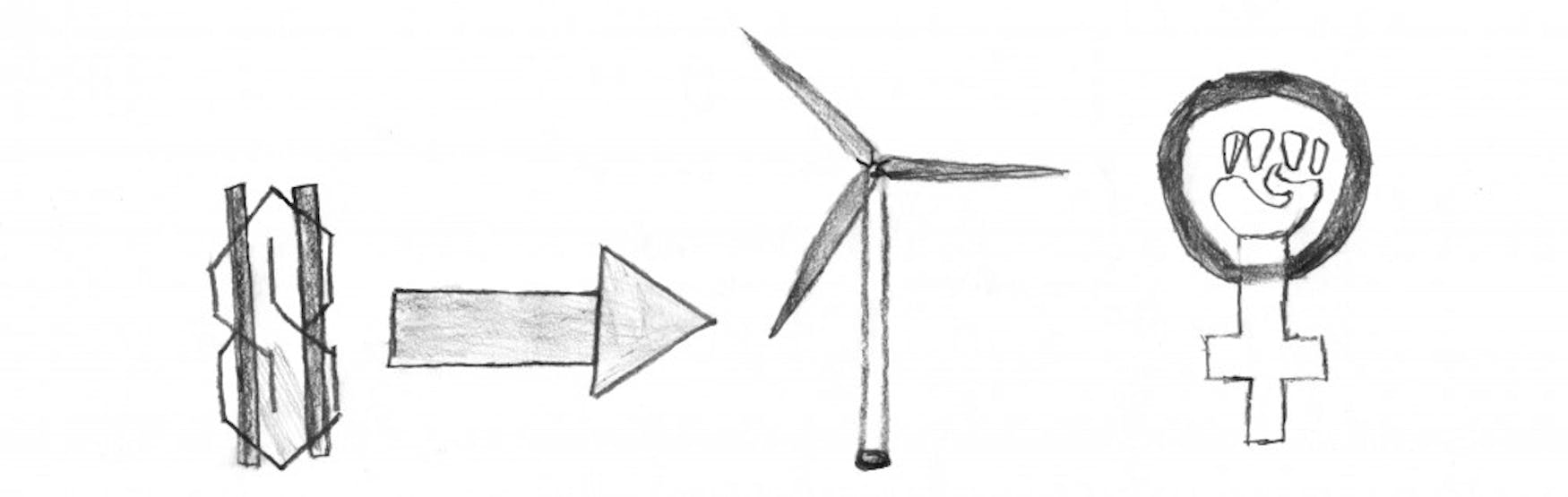

Impact investing for dual financial and social returns

For more than two centuries, capital markets have provided a place for companies and governments to raise money to finance activities. It’s the largest game in the world: part strategy, part luck. Companies issue debt or equity to expand operations by opening new business lines, executing mergers or acquisitions, etc. Investors, in turn, pour their capital into businesses with attractive financial prospects based on the security’s price and risk. If the price is good, the risk is acceptable and the firm’s earnings are expected to increase at a rate higher than the rest of the market, then the company is a buy.

Until recently, investors’ due diligence generally consisted of either fundamental or technical analysis. A fundamental strategy seeks to determine a firm’s intrinsic value based on a financial, economic and qualitative data, while technical analysis examines trends in price or volume. From the investor standpoint, the sole objective of the undertaking of this risk was to reap financial returns and outpace inflation.

But in the 1970s, a form of investing called socially responsible investing began to take root among Catholic organizations in the United States. They began to screen out “sin stocks” — or companies engaged in the perceived-to-be-immoral practices of gambling, guns, tobacco and more. Since then, the popularity of SRI has skyrocketed. According to the US SIF Foundation, by the end of 2017 more than one of every four dollars under professional management in the United States was invested according to SRI strategies, an amount totaling more than $12 trillion.

The diversity of SRI options has also grown. Investors now have access to more socially responsible investment vehicles than ever before. Many institutional money managers, Vanguard and Blackrock included, offer mutual and exchange-traded funds which include special environmental, social or governance screens as a core part of the fund’s overall strategy.

Vanguard’s ESG US Stock ETF, for instance, screens out companies engaged in fossil fuels, nuclear power, weapons, and other supposedly unethical industries. According to its prospectus, the fund also excludes “companies that do not meet the labor, human rights, environmental and anti-corruption standards as defined by the U.N. global compact principles, as well as companies that do not meet appropriate diversity criteria.” Other specialized funds (ticker symbols: PRID, HONR) screen companies exclusively according to their level of inclusion of members of the LGBT community or veterans.

“Historically, the majority of positive social and environmental impact has been driven through volunteerism, charity and policy making,” says Derek DeAndrade, co-president of MIT Sloan’s Impact Investing Initiative club. Prior to the revolution in impact investing, investors traditionally had two options for their money: invest for market-rate returns or donate to philanthropic causes. Now that is changing; no longer are the two worlds siloed as they once were. Now investors are beginning to “do well by doing good” — to use the Benjamin Franklin line oft-quoted in the industry — by parking their investable assets in companies with positive impact.

Of course, this model is far more sustainable. By investing rather than donating, investors generally receive back their principle plus interest for debt, or capital gains and dividends for equity, enabling these individuals to plow back their returns into a company aligned with their values. It also helps non-profits by incentivizing small ones to become self-sustaining rather than remaining dependent on their fundraising department.

On campus, Professor Michael Appell of the Heller School for Social Policy teaches a course on the “triple bottom line,” an approach to business value-creation that expands the definition of company success from just the financial to social and environmental as well. “Little by little,” he says, “more and more companies are associating excellence with activities that promote healthy products and lifestyles, establish alliances with key NGOs, respect human rights, reduce waste, and protect the planet.”

And with the intergenerational transfer of wealth, there’s increasing demand to invest in these kinds of companies. According to a 2015 Nielsen report, 73 percent of millennials are willing to pay more for goods and services from sustainable companies, up from 55 percent in 2014.

Given that money talks, this could tip the scales. If consumers and investors continue to emphasize their concerns on sustainability, companies will adapt accordingly.

To amplify their voices even more, many socially-responsible fund companies engage in shareholder advocacy to further their interests. In early March, for instance, Boston Common Asset Management reached a significant agreement with Home Depot for the company to reduce carbon emissions by 40 percent by 2030 and 50 percent by 2035.

Green Century, which offers several fossil-fuel-free investment products, also engages in proxy voting to encourage companies to pursue positive environmental impact. Their currently featured campaign is tropical forest protection, which seeks to prevent the loss of animal habitats and halt climate change. With rigorous shareholder advocacy, Green Century in 2012 “helped secure a zero-deforestation commitment from Wilmar International, the world’s largest palm oil trader, that will avoid 1.5 gigatons of carbon pollution between 2015 and 2020.

Marion Rockwood, Associate Portfolio Manager at The de Burlo Group, believes that companies who incorporate the triple-bottom line approach will perform better financially in the long-term. “Those firms that take a wider view of their stakeholders to include employees, customers, and community will also have the most benefit to shareholders,” she says.

The question of whether ESG-screened funds perform better than their more traditional counterparts is difficult to answer. “From a financial return perspective, impact investing is still seen as inferior to traditional investing,” says Derek DeAndrade. But several studies have shown otherwise. More than 90 percent of studies have shown a nonnegative correlation between ESG-screened funds and long-term performance, according to Gerold Koch of Deutsche Asset and Wealth Management. In 2015, the firm conducted a meta-study alongside Hamburg University that aggregated evidence from over 2000 empirical studies. They discovered that ESG and financial performance were positively correlated in the vast majority of cases.

“ESG can uncover non-financial risks that may become costly for companies in the future, in effect turning them into financial risks – for example, a firm can experience an unforeseen environmental crisis caused by poor production processes and magnified by weak disaster management procedures,” Koch says.

Professor Appell agrees with this sentiment and predicts that “ESG investing will become so refined that it becomes the default approach - simply the best practice integrated into all major investment systems.”

Investors seeking a financial return alongside a social or environmental one have can invest not only in public equity, but also fixed income and alternative asset classes such as private equity, venture capital, property funds such as real estate investment trusts and hedge funds.

The Boston Impact Initiative, for instance, is a $10 million place-based social venture fund that invests in companies pursuing racial and economic justice. One of their portfolio companies, for instance, is CERO, the Cooperative Energy Recycling and Organics, which is “a worker-owned cooperative that collects waste from local businesses.”

Root Capital also has a fascinating model — investing in the growth of agricultural enterprises across the rural developing world. And Accion, based in Cambridge, offers fintech startups and microfinance institutions small loans with reduced interest rates, amongst other products, to expand traditional access to the financial markets.

Social-impact bonds have also become popular in recent years, pioneered by organizations such as Social Finance and Third Sector Capital Partners. Through this model, investors pay for the up-front provision of social services with the promise of principal reimbursement — plus interest — from the government, should certain pre-set outcomes be achieved as determined by a third party.

As you can tell, impact investing is an exciting and growing field, changing the way companies do business and investors decide where to put their capital. With more sustainable investment options than ever before, we can use the capital markets not only to achieve financial returns but effect social and environmental change as well.

Please note All comments are eligible for publication in The Justice.