Deserts, blood and ghost towns: Chile’s loneliest open-air museum

The buzz of the A-16 highway keeps the travelers awake amidst the deadly silence of the Tarapaca desert. Just over 33 miles east of Iquique, Chile, the ruins of the Humberstone and Santa Laura Saltpeter Works succumb to the heat and oblivion of a brutal past.

A TOWN IN RUINS: Rust and solitude corrodes Humberstone’s facilities.

Glowing in the distance, the nearly 150-year-old inactive workshops welcome the visitors to the largest saltpeter deposit in the world. The ghost town’s facilities, formerly known as La Pampa, have been restored into an open-air museum that preserves and honors the lives of its long-gone inhabitants: the Pampinos.

During the industrial boom of the 20th century, thousands of workers from Chile, Peru and Bolivia migrated to the hostile Pampa in search of economic prosperity. Saltpeter was mined to produce sodium nitrate, a natural fertilizer responsible for boosting Chile’s economy.

For over a century, these workers and their families fought for social justice in one of the world’s most inhospitable environments. In the remote desert, they led general strikes against extremely poor working conditions. For decades, the Pampinos endured abuse and exploitations from the multinational saltpeter industry. After months of demonstrations that spread fiercely across the region, the exhausted inhabitants of La Pampa marched hundreds of miles to the port city of Iquique, where negotiations were being held.

Confined in the city’s school, la Escuela Santa Maria de Iquique, the workers were brutally repressed by the government. The series of protests resulted in the mass-shooting of over three thousand workers and their families by the indiscriminate fire of the Chilean army. The Massacre of the Santa Maria de Iquique School remains one of the darkest chapters in the history of the Andean country.

THE DRIEST DESERT IN THE WORLD: A visitor avoids the heat in front of the Humberstone Theater.

Stepping carefully through the ruins, the visitors watch out for the rusty infrastructure shaken by a sudden burst of wind. Through the empty streets, various signs warn of the imminent danger ahead: unstable ceilings and walls about to fall at any moment. On top of the inevitable decay, the town has been further damaged by a recent wave of earthquakes. In spite of the conservation efforts, the modest houses made of white caliche are covered in cracks and rust, a humbling reminder of the destructive power of time and nature.

Once inside, the tiny houses resemble an improvised gallery. Hundreds of artifacts present the life of their past owners like pieces of an incomplete puzzle. Some rooms store their belongings: scribbled notes and dining tables with cutlery on them. The doors left carelessly open make us wonder: did everyone disappear in the blink of an eye? In the childrens’ rooms, wooden dolls and tin guns give us a short glimpse of the simple life that went by in spite of the surrounding tragedy.

Nevertheless, not everything was back-breaking work in the heat of the desert. The Pampino people had a rich culture and lifestyle, making the most out of the scarce resources provided by the environment. Though the saltpeter economy started to decline worldwide during the Great Depression, the inhabitants of La Pampa pushed through the hardships of the mining lifestyle until the bankrupt facilities were abandoned in the 1960s.

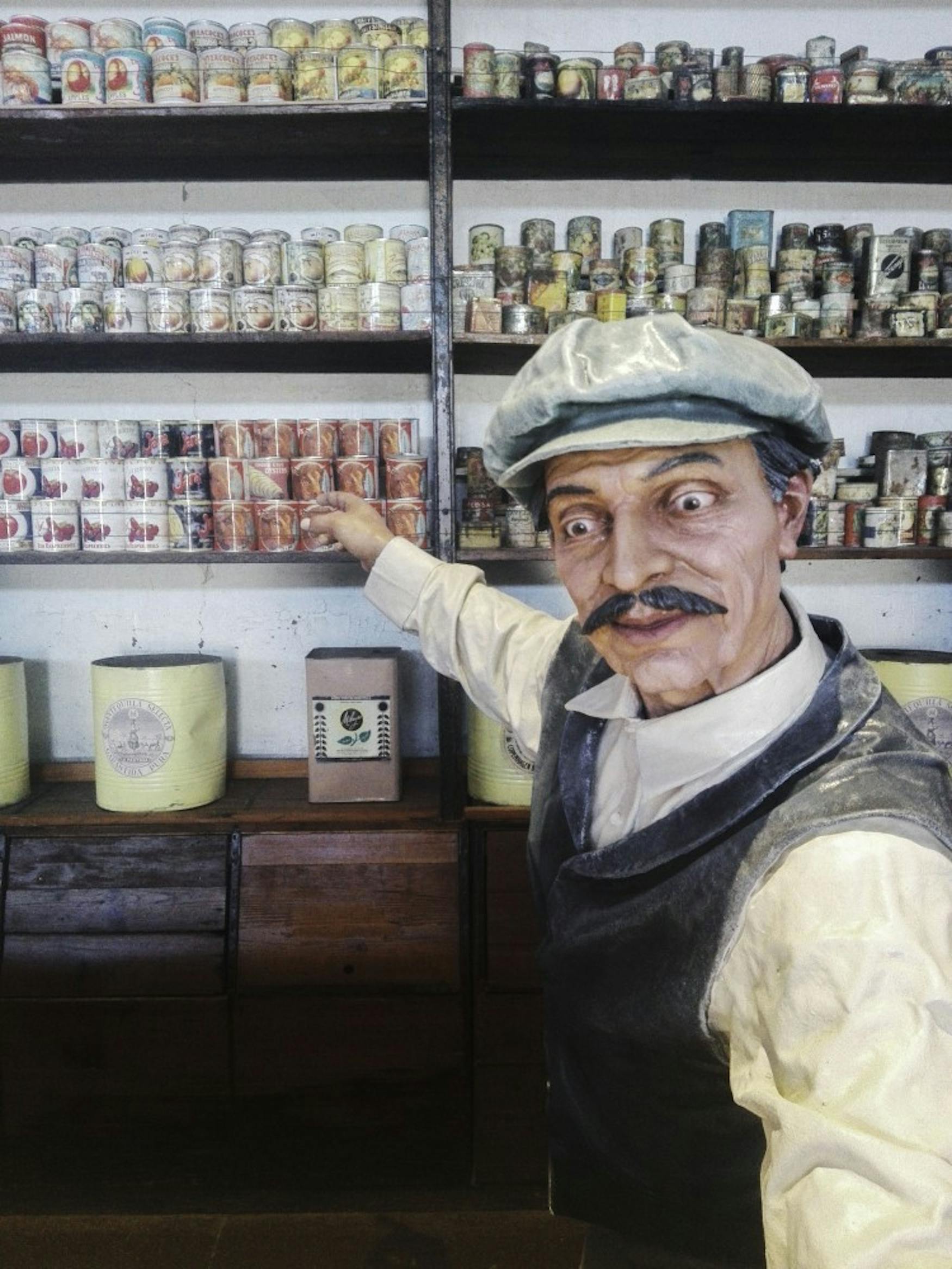

Smiling for the camera, some visitors take pictures in front of the buildings that have been recently restored to their former glory: a ballroom, a church, a hotel, a school and a theater. Each one brings back the adventures of the men and women that once danced, laughed and loved here. Human statues made of clay trick visitors into thinking they are not alone as they walk through the labyrinthic Pulperia, the only convenience store in the community. Here, the miners were obligated to exchange the tokens they received as salary for goods, food and other necessities. The market was reopened to visitors in 2016 after 300 million Chilean pesos were dedicated to the preservation of its invaluable cultural legacy. The donations were made by the National Ministry of Economy, Investment and Tourism and the Regional Government of Tarapaca, among other institutions.

Throughout the years, the Saltpeter Museum Corporation has turned a long-forgotten town into a heart-wrenching journey back in time. Recognized as a World Heritage Site in 2005 by UNESCO, the Humberstone-Santa Laura complex preserves the last memories of the rise and fall of Chile’s saltpeter economy. More profoundly, it exposes the crimes committed against its people — which is a much more important mission.

Vestiges of cruelty loom around every corner, yet the exceptional loneliness of the landscape is far from terrifying. Humberstone is a vivid reminder of humans’ capacity to adapt and their will to fight against the inevitable twists and turns of adversity. Sitting on top of a hill by the mine’s southernmost border, visitors look in awe at one of the most breathtaking views of the forgotten city: an infinite horizon where nothing survives except the salty breath of a burning desert.

Please note All comments are eligible for publication in The Justice.