A love letter to affirmative action

When I read the takeaways from Students for Fair Admission v. Harvard, I stepped out onto the top of the Rabb Steps the next day and took a good hard look at a 2:00 p.m. rush, a hundred strong. I felt two things. The first was immediate relief. Affirmative action is safe for now, and the diversity I saw only stands to grow from here. The second feeling I had, however, was more malignant. Would this campus be better with less people like me?

Anyone who didn’t read my last article on Harvard’s swampy affirmative action situation might be surprised to hear that I almost did a backflip reading Monday's District Court decision on the matter. By blood I’m 100% Korean American, which means it's still harder for people who look like me to get into college in America compared to people of Latinx or Black descent. However, I firmly believe it’s still harder for people in these racial and ethnic backgrounds to put things on their applications because of their systematically marginalized position in American society. This is why my glee seems to betray my interests as an Asian American — race-blind college admission is not the way to achieve greater equity in higher education.

A very brief background is in order. Students for Fair Admission is an organization created in 2015 by a group of parents, students and sympathizers to bring a suit against Harvard for alleged race-based discrimination against Asians in their admissions process. SFFA advocates for race-blind admissions. I asked Professor Daniel Breen (LGLS) to help me decode what exactly SFFA had to prove to get their way. Even though Harvard is a private institution, in deciding whether or not the Civil Rights Act was violated, it is held to standards that would be applied in an equal protection case under the 14th Amendment. Professor Breen explained that “if Harvard is shown to take race into account … that decision must be evaluated by a federal court under the strict scrutiny standard — and those are the keywords, scrutiny. What that means is Harvard has got to show that they have a compelling interest to take race into account in admissions decisions.” All this is to say, Harvard must show that it is using race specifically as a means of promoting diversity — which was found to be a compelling enough state interest in Regents of the University of California v. Bakke. In all cases, race must be a factor that only helps rather than hurts a student’s chances of getting into school.

In the most recent Sept. 30 ruling, Judge Allison D. Burroughs found Harvard not guilty of race-based discrimination in their admission process. “I think it’s a good opinion,” said Professor Breen. “It really relied with great fidelity on [Grutter v. Bollinger], and one thing that was not good for the plaintiffs who were challenging Harvard was that former Supreme Court Justice Sandra Day O’Connor in the Grutter case actually praised the Harvard admissions system.” The aforementioned case, Grutter v. Bollinger, was a 2003 Supreme Court case that found race considerations at the University of Michigan Law School to be lawful, relying on precedents set in previous cases; Harvard’s admissions program was used as an example in one such case, Marks v. United States, and the admissions process was found similar enough to Michigan’s to be compared. In Grutter v. Bollinger, Justice O’Connor’s statement knocks down part of SFFA’s argument in short order: “The Law School’s current admissions program considers race as one factor among many, in an effort to assemble a student body that is diverse in ways broader than race. Because a lottery would make that kind of nuanced judgment impossible, it would effectively sacrifice all other educational values, not to mention every other kind of diversity.” Race-blind admissions would be that lottery.

Even so, is color just being used as a stand-in for multiple kinds of diversity? As the problem has been framed to me before, “What about the Black student fresh out of boarding school, whose parents are both doctors, with houses in the Hamptons etc.? Is that really diversity?” As it stands, the aforementioned family is much more rare, according to statistics, than an extremely well-off Asian family.

The socioeconomic differences are both real and dramatic. According to the United States Census Bureau, the bottom fifth of Asian households were bringing in a mean of $16,497 in 2018, adjusted for inflation. The top fifth brought in a mean of $303,316. This is compared with Latinx households, whose bottom fifth brought in a mean income of $12,409 and top fifth $179,639. For Black families, it was $7,686 in the bottom fifth and $154,822 in the top fifth. In almost every fifth bracket since 2002, Asians have had a higher mean household income than both of these other racial demographics. All this to say, race is the unhappy mascot of socioeconomic inequality in America en masse, and race is just being used as a proxy to sift through mounds and mounds of applications.

What I’m saying is not that discrimination against Asian Americans just isn’t bad, so we should all just suck it up and relinquish our spots at top universities. The Privilege Olympics are not a productive game to play in this situation. However, the question remains: is there a better proxy? This an extremely difficult question, says Professor Yuri Doolan (AAPI): “Poor kids go to poor schools in the United States … and come to school very differently prepared than students who grew up in wealthy suburbs.” From our conversation, it became clear that it would be ideal to separate socioeconomics from race, and it would be ideal if all ethnic backgrounds did enter into the world of higher education equally prepared, but race-blind admissions promotes a version of meritocracy that in aggregate only benefits the most privileged in America.

The notion that Asians are presented with the same discrimination and just hitting the books harder is completely fabricated. The “model minority myth” is the idea curated post-1965 that used Asians to show that if someone studies hard enough, they can achieve success as compared with other “lazier” minorities, all supported by the numbers seen before. NPR references Janelle Wong on this subject, the director of Asian American Studies at the University of Maryland, College Park. Wong says that the model minority myth acts as part of a conservative agenda by “ignoring the role that selective recruitment of highly educated Asian immigrants has played in Asian American success followed by, making a flawed comparison between Asian Americans and other groups, particularly Black Americans and to argue that racism, including more than two centuries of black enslavement, can be overcome by hard work and strong family values.” This trend of having races pitted against one another is not unusual. “Historically, Asians have been used as weapons of anti-Blackness.” says Professor Doolan. This idea of race-blind admissions buys into this racist system, and SFFA is not speaking for the many groups of Asians that need representation, rather those who can afford it.

Be that as it may, because I got into an elite college, one might say I wasn’t affected, and I shouldn’t have any vested interest in this issue anymore. It’s easier for me to take the moral high ground and be woke about privilege and slam the admissions door in the face of all my fellow Asian Americans, because the precedent set in this case doesn’t affect me. To this I would draw attention back to the case.

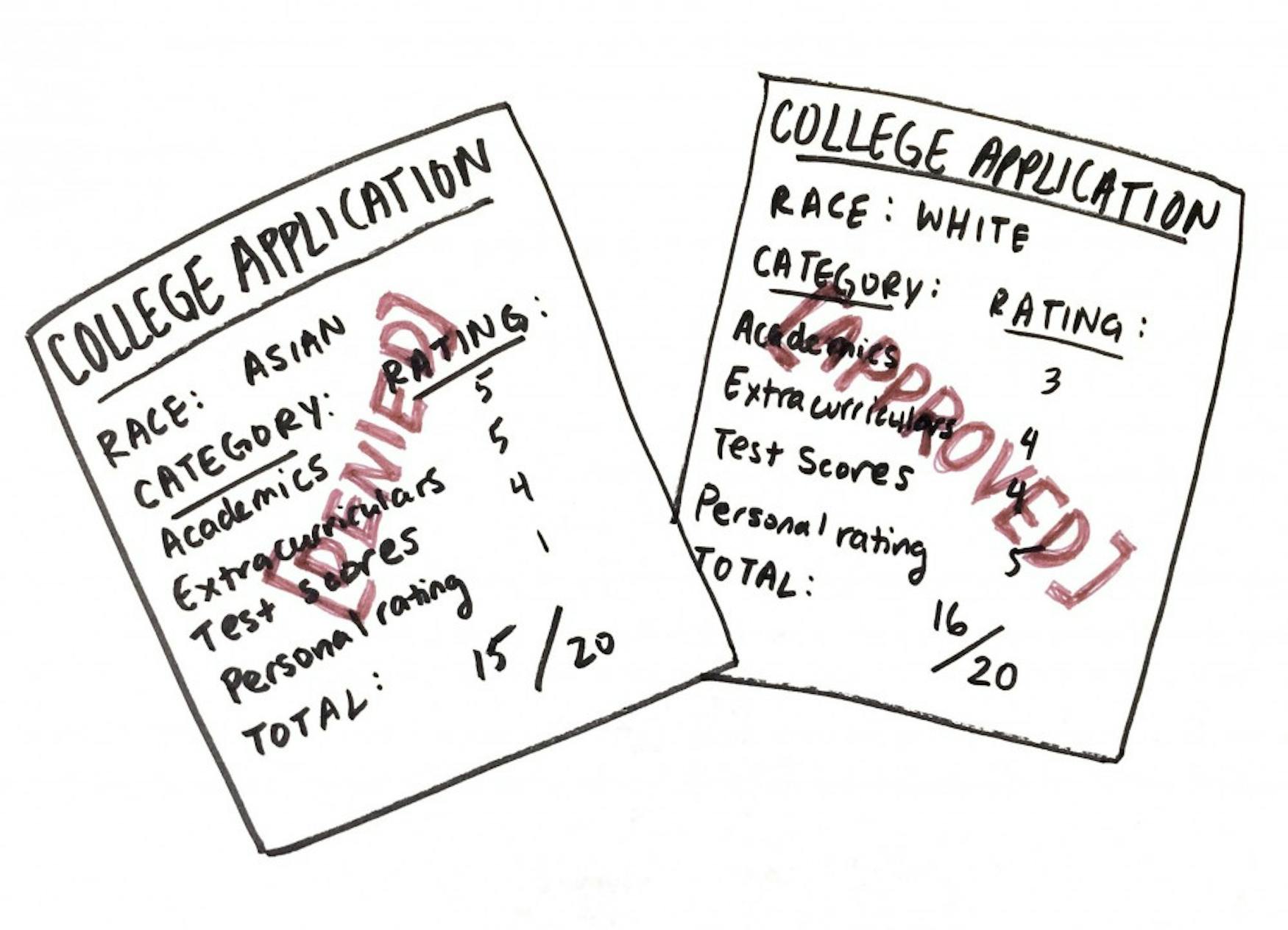

According to the New Yorker, Harvard’s Office of Institutional Research did collect findings that pointed towards the admissions process being biased against Asians in 2013: “Among the most striking findings was that Asians were admitted at lower rates than whites, even though Asian applicants were rated higher than white applicants in most of the categories used in the admissions process, including academics, extracurriculars, and test scores. One exception was the ‘personal rating.’” Harvard isn’t absolved. SFFA is on the right track, but there is still work to be done, because the facts now show that kids like me still have to appear un-Asian on their college application to get in.

This is related to one more major problem. Slate says that athletes, legacies, “Dean’s interest,” and children of faculty (called ALDC’s collectively for short) are still admitted at a disproportionately high rate. Article after article confirms that caucasians are still the ones benefiting the most from higher education admissions in America. However, I am not villainizing caucasian people. I am saying that college admissions are a microcosm of the multiethnic fabric of America, and it’s a lot more wicked in a much bigger way than me or SFFA could ever imagine. So to the question of whether this still affects me: This case sets a precedent. Don’t dismantle affirmative action, but I don’t want to have to do things so that I can appear less Asian to get opportunities. I don’t want that for anyone.

After all this, will I check my admissions file? I don’t want to find out whether or not I should spite my identity even more. It’s not that ignorance is bliss, because it’s not — I’ve done my reading and my research and I can live blissfully by looking forward. I’m Asian and I like it that way.

Please note All comments are eligible for publication in The Justice.