Scholar discusses women in colonial transatlantic convict trade

Prof. Robin A. Robinson, a resident scholar at the Women’s Studies Research Center, told the true story of a young English woman subject to the transatlantic convict trade to colonial America.

Prof. Robin A. Robinson PhD ’91, a professor of sociology at the University of Massachusetts Dartmouth and a resident scholar at the Women’s Studies Research Center, shared excerpts from her unfinished novel about young English women criminals subjected to the transatlantic convict trade, as well as her research on trafficked women in colonial America, at the WSRC on Tuesday.

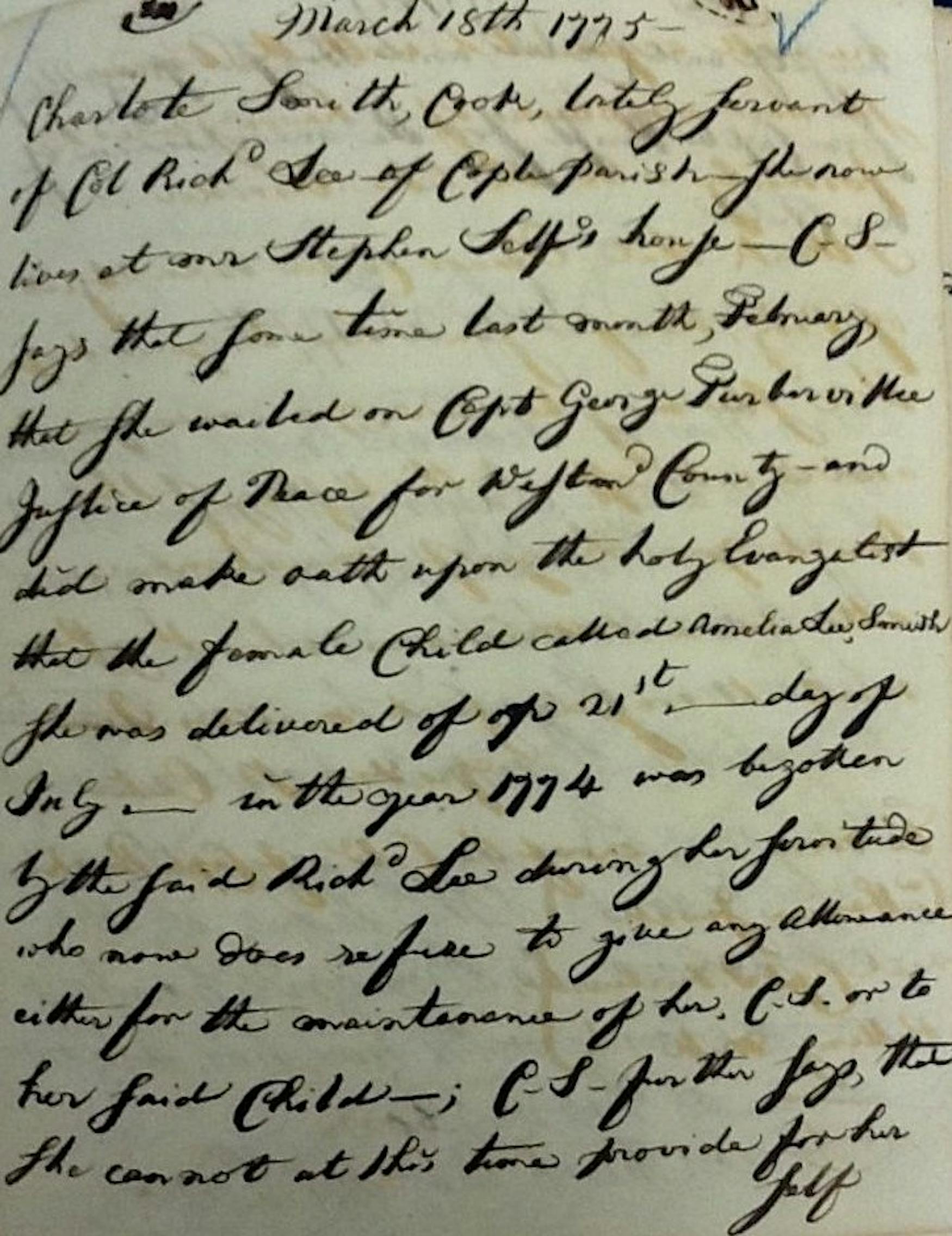

Robinson’s novel re-imagines the experience of Charlotte Smith, a historical 16-year-old English girl who was convicted of stealing a watch and sentenced to transportation in 1768. Robinson’s account provides a glimpse into Smith’s internal narrative as she withstood wretched conditions aboard the ship, asserted her dignity when she gave birth to a daughter by her master and reminisced about her past life in England.

Little is known about Smith, so Robinson relied on her own creative license to fill in the blanks. In the novel, Robinson made the stolen watch a thimble, but kept the known fact that Smith bore the child of Richard Henry Lee, a delegate to the Continental Congress and signatory of the Declaration of Independence, for whom she served as a cook for seven years. Despite laws ensuring her continued servitude, Smith requested relief from her work in order to care for her child, which indicated to Robinson that Smith was “no wilting violet.”

Robinson’s characterizes Smith as a practical, resilient woman who is nonetheless depressed by her circumstances. “I am sinking into dozy boredom waiting for my next set of orders,” Smith says when she is working for the Revolutionary Army. “I am so much better than cooking dead pig meat to feed the boys when they return from the forest.”

The transatlantic convict trade preceded the better-known transport of English convicts to Australia by more than a century, lasting from approximately 1649 to 1785, although it was not officially codified until 1718. Faster and more covert than the African slave trade, the trafficking of English convicts — known euphemistically as “imported Christian servants” — was a method of providing cheap labor to the colonies in America without the fear of a Black slave revolt while also providing a legal punishment in place of the increasingly unpopular death sentence. Although both men and women were trafficked, there was a premium on young women; between 7,000 and 8,000 girls were subjected to the convict trade.

Female convicts averaged 16 years of age when they were sentenced to transportation, and their crimes typically involved petty theft of linen such as a shirt or a handkerchief, according to Robinson. Once sentenced, the girls would be moved into a “hulk,” or prison ship, where they would be sold to ship captains and then auctioned off when they reached the colonies, where they would typically serve for seven years. Furthermore, the masters of these girls were socially and financially incentivized to impregnate their servants, as servants would then be bound to an additional two years of service and the child would be born into servitude, according to Virginia tax law. This practice provided more cheap labor and increased the white population in the colonies.

These women met a variety of fates. Some died, some stayed in America, some returned to England and some of those were re-arrested and sent back to the colonies. As an example of a transported woman who achieved liberty, Robinson recounted the story of Mary Stiles, who married a fellow convict after serving her sentence, purchased land on the Potomac and lived “to a ripe old age” as a free landowner.

Gilda Geist ’22, who assisted Robinson in her research, also spoke. Geist spent a semester helping Robinson scour court records from the Old Bailey, the major criminal court in England, via an online database. Geist compiled names, dates and details from each case in order to catalogue them and determine which would be helpful for Robinson’s research. Other sources Robinson used to compile data included birth and baptism records, plantation records and resources from the Sallie Bingham Center for Women’s History and Culture at Duke University.

Robinson holds a PhD in Social Policy from Brandeis University’s Heller School of Social Policy and Management and a doctorate in Clinical Psychology from George Washington University. In 2017, Robinson was selected as a Fulbright Research Scholar to study sexual violence in Hungary, according to an article released by University of Massachusetts Dartmouth.

—Editor’s Note: Gilda Geist is a Justice News Editor. She did not edit or contribute to this article.

Please note All comments are eligible for publication in The Justice.