CUNY professor shares experience discovering police file on herself

Katherine Verdery discussed her book about her discovery of a Romanian secret police file about her.

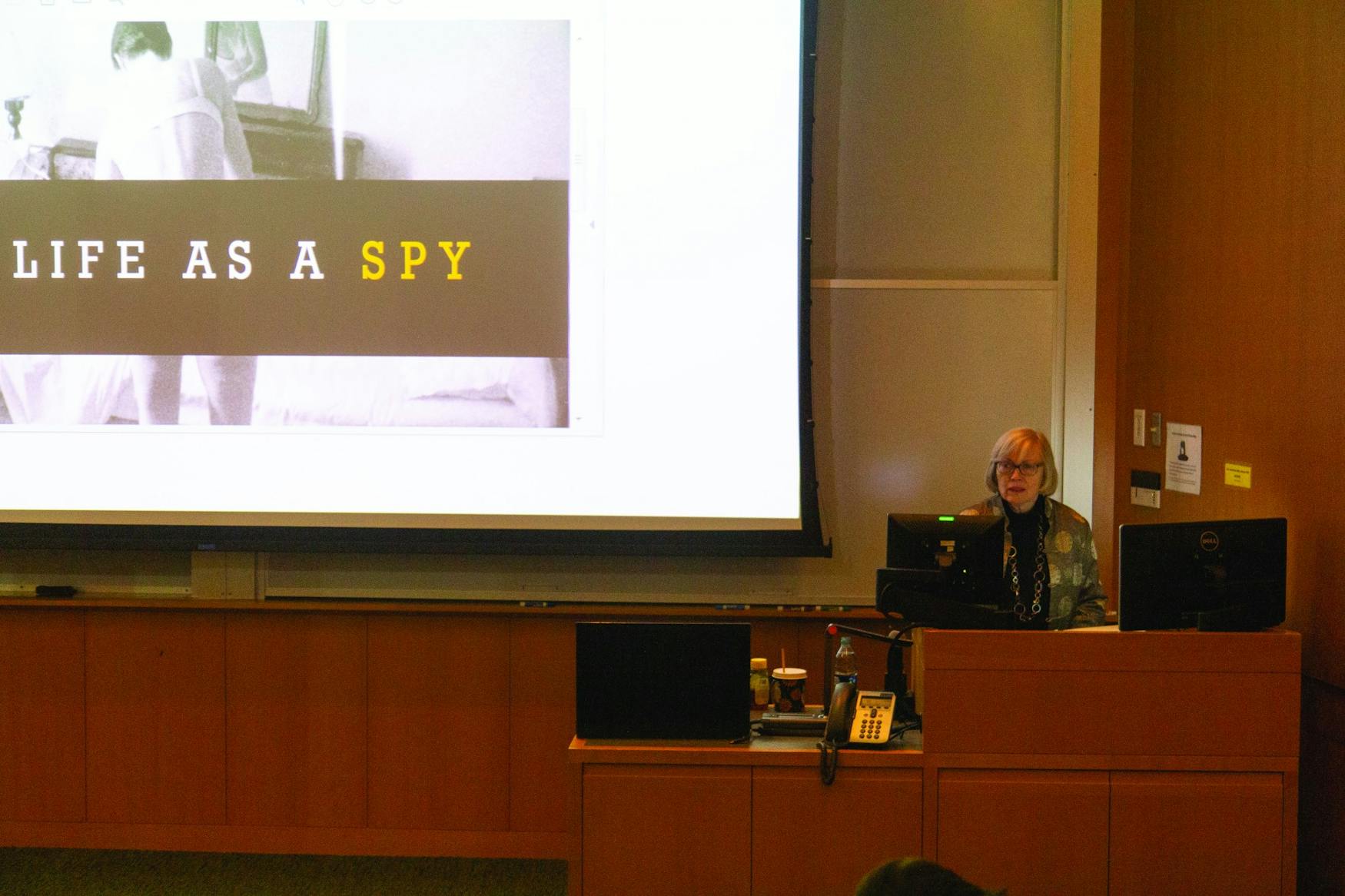

City University of New York Professor of Anthropology Katherine Verdery gave a talk on Friday about her discovery of a Romanian secret police case file about her years of anthropological fieldwork in 1970s Romania. She has written about these experiences in a recent book titled “My Life as a Spy: Investigations in a Secret Police File.”

After the fall of General Secretary Nicolae Ceauescu’s Romanian government in 1989 and the fall of the Soviet Union in 1991, the National Council for the Study of the Securitate Archives was created in 1999 to probe the archives of the Securitate, the former Romanian secret police. Verdrey worked as a researcher for CNSAS and gained access to her own case file in 2008. She learned that she was incorrectly suspected of being a spy and was known by the Securitate as Vera, taking the first three letters of her last name and making it “a nice Russian name,” as she later learned from a former agent involved with her file.

The case file began near the beginning of her stay in Romania, Verdery said. She explained that she was touring the Transylvania region by motorbike, looking for an ideal site to perform her fieldwork. According to Verdery, she was riding toward the setting sun and found it hard to see. This led to her riding into a restricted area, missing a sign that warned against foreigners trespassing. From then on, she said, her time in Romania had been closely recorded by many people she interacted with, including some of the people she considered her closest friends.

Verdery described how her research into the case file was “the most difficult research [she] had ever done.” She had to fully engage with her research while also “standing back and analyzing those feelings and experiences.” She was not alone in her conflicted feelings. According to Verdery, many Romanian scholars have written furious pieces denouncing the immorality of the Securitate’s excessive surveillance.

As her research continued, Verdery explained that her attitude towards her case file gradually changed. At first she felt both “appalled and depressed” as well as “violated and angry,” considering that she was spied on personally. Eventually, however, she began to find the research interesting from an academic perspective. She realized that the Securitate was reasonable in its wish to prevent “sabotage and spying.” She also recognized that her behavior could easily be perceived as suspicious, so the agency had very good reason to compile information on her. However, she also argued that spies serve as a function of fear to justify systems of oppression. Therefore, even if the Securitate had little concrete evidence to support Verdery’s identity as a spy, it was valuable for the Securitate to gather information on her and other scholars, because it increased the Securitate’s legitimacy.

One of Verdery’s closest friends was a man she referred to as Silviu. She explained that she was especially shocked to read in her file that he discussed her supposed spy status with the Securitate a number of times throughout her stay in Romania. Through these communications, he supposedly confirmed Verdery’s identity as a CIA agent and a Hungarian spy. Verdery explained that Hungarian-Romanian relations have historically been tense due to Hungary and Romania fighting on opposite sides during WWI, which resulted in the transfer of the Transylvania region from Hungary to Romania.

Verdery said that during her stay in Romania, Silviu told her that he was being harassed by the Securitate for unexplained reasons. According to Verdery however, he implied to her that he was refusing to cooperate. She explained that she was particularly “enraged and distressed” by the reports of Silviu’s informing because they “incorporated bald-faced lies coming from someone who appeared to be a person of integrity and good judgement.” However, she eventually forgave him, realizing that her relationship with Silviu and other Romanians had to be considered “in the context of the larger set of relationships in which they are embedded.” If she thought of their actions as a betrayal, she said, she would be implying that she was more important than their other relationships.

One central question Verdery asked was whether her fieldwork could be considered as a type of spying. Over the course of her research, she interviewed a number of people involved with her case file, including three former Securitate officials. Each official had a different interpretation of what constituted a spy, according to Verdery.

According to the officers, a spy is a person who either collects political, economic or social information about a population’s state of mind, gathers information to “propagate a negative image of Romania abroad” or works for intelligence agencies, Verdery said. She pointed out that she is perhaps implicated by the first two definitions, but not the third.

Verdery concluded her talk by discussing her thoughts about Russian interference in the 2016 United States presidential elections. She argued that this interference resembles the central goal of the secret police — “to sow chaos, disorder and confusion to keep people off balance.” She recalled one paper by a Bulgarian colleague arguing that the secret police have become “new businessmen, not by following the rules of capitalism as westerners expected.” Instead, the colleague argued that “it looks like the collapse of the socialist system ushered in not free markets and democracy but a worldwide mafia of oligarchs with secret police connections and relatively high solidarity.”

Please note All comments are eligible for publication in The Justice.