Music in the time of COVID-19

It is unbelievable that, as a sophomore, I’ve spent half of my college experience so far in the COVID-19 pandemic. People call it the new normal, but it will never be normal. As many of us are physically hundreds of miles away, language becomes pale, and our interactions are limited to just a small box on our computer screen. As we are apart from our friends and family, I turn to music to find tranquility. In April, I attended the “Together At Home” online concert initiated by Lady Gaga. When I saw the number of attendees climbing up in the lower-left corner of the video, which showed that millions of people across the globe were attending this concert with me, I felt supported.

I am not the only one who found togetherness through music. Ever since the pandemic began, people have been paying more attention to the research of music and its support to people during a time of pandemic. On Sept. 17, the Brandeis Music Department invited Prof. Remi Chiu from Loyola University to talk about music in the time of the Bubonic Plague and its application in the current situation.

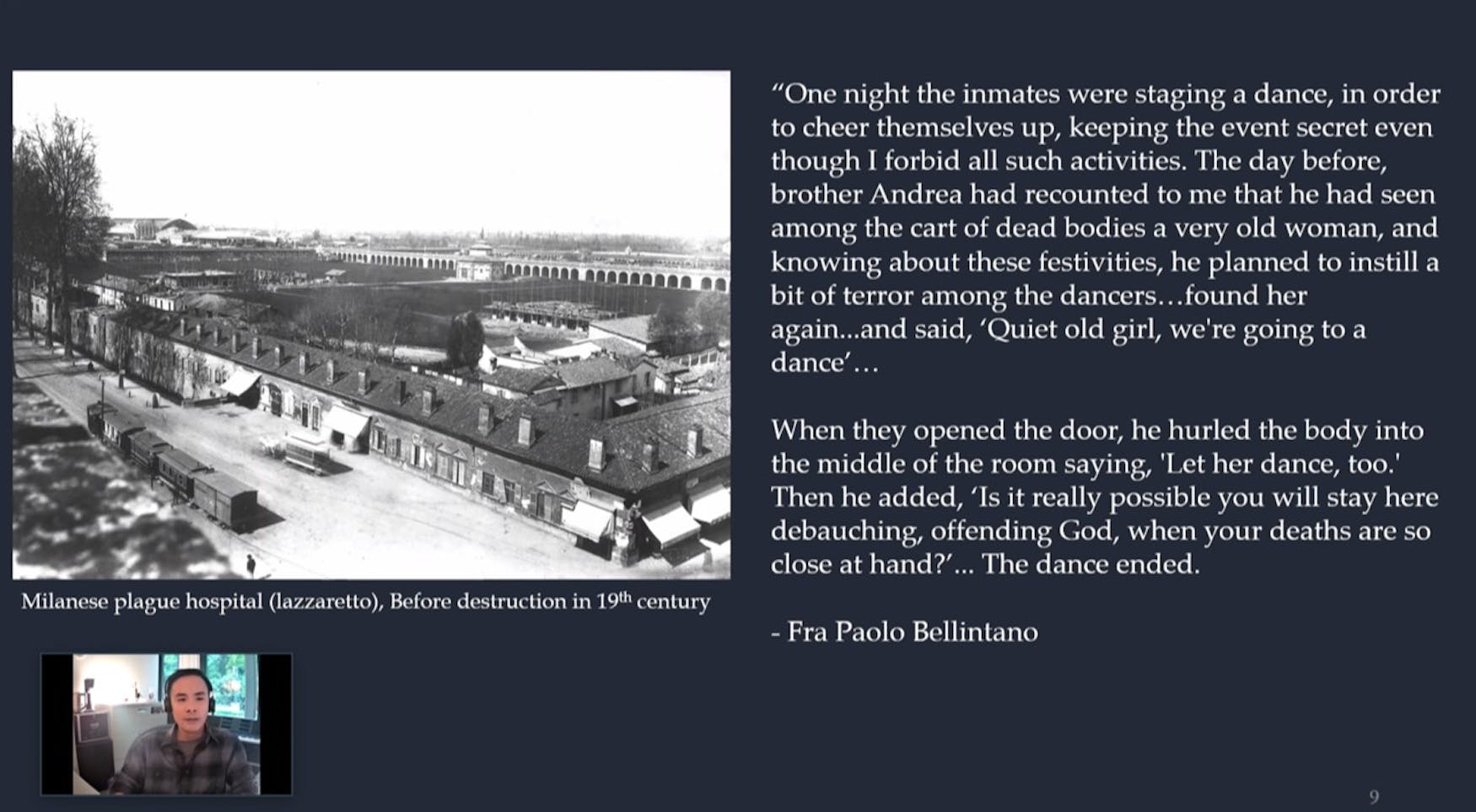

To study music in the time of the pandemic, musicologists turned to studying plagues in history — diseases that were widespread across continents, resembling today’s situation. Plagues had three major breakouts in human history: the Justinaianic in the sixth century C.E., the Black Death in the 14th century and the re-emergence of the Bubonic Plague in Asia in the 19th century. The most widely discussed topic was the music of the European Black Death, which took away one-third of the continent’s population. Prof. Chiu’s colloquium paid special attention to the 1629-1631 bubonic plague in Italy — which is also known as the Great Plague of Milan — that resulted in a death toll of approximately one million. The outbreak started in Trent, Italy and quickly spread to Milan. In the 17th century Europe, outbreaks like this were often understood as the punishment by God. The Church was in charge of providing care, especially spiritual remedy, to the patients as well as all the residents of Milan. Under Archbishop Carlo Borromeo’s regulation, residents in Milan were put into general quarantine in their homes, and the infected individuals were isolated in the plague hospital Lazaretto.

Patients in the Lazaretto were put into 40 days of isolation care, which was speculated to be in accordance with the 40 days temptation of Jesus in the desert. Music played a critical part in the care for patients in Lazzaretto. Patients were told to enjoy music to calm their minds. Outside of Lazzaretto, music was used to channel faith. Milan organized parades where participants sang litany. The litany was written in a few easily understood Latin sentences mixed with Roman languages, and could be easily memorized or sung by common people. People would hold items representing local spirits, saints and their ancestors. As the breakout escalated and people were put into general quarantine at home, Borromeo still figured out a way to connect pious believers together. When the bell rang in the church, he had musicians playing at corners of the city. People then sang litany from their windows. Music tied believers closely to their God, and also tied residents of Milan together in a shared spirit.

This tradition has been passed down from that time. In early spring this year, my friend very far away in Italy shared a video she took from her balcony featuring people singing from their windows. The same thing seemed to happen everywhere in Italy, and around the world. People sang folk songs, patriotic songs, songs with local spirits. Chiu showed us a video featuring several people singing the song “O mia bela Madunina,” the local song for Milan. People recorded their parts at home and pasted different parts together to produce a complete song. Another video featured musician Raffaele Kohler playing “O mia bela Madunina” on the trumpet from the window of his apartment. Hundreds of years later, people still sing and play music from their windows.

Unlike people who lived during the Plague, the purpose of singing is no longer limited to religious reasons. Chiu showed screenshots of Spotify COVID-19 playlists and pointed out a funny juxtaposition of two playlists next to each other: one with the theme of praying to God, and the other named “(Expletive) it, COVID party.” Music became a common language where people shared emotions with each other.

Nevertheless, the sense of support and social engagement individuals gained from music in pandemic times never changed. I cannot look through my computer screen and know every person attending the “Together At Home” concert streaming. The attendees probably represented dozens if not hundreds of cultures and creeds. But I know at that very moment that we are together, we support each other and that we pray together for this pandemic to end soon.

Please note All comments are eligible for publication in The Justice.