Students share their experiences with accessibility on campus

Following several interviews with students with disabilities, the Justice uncovered ways in which the University has struggled to support these students.

On July 25, 2020, the United States celebrated the 30th anniversary of the passing of the Americans with Disabilities Act. The ADA protects people with disabilities by prohibiting discriminatory behaviors against them in workplaces, government entities and private entities that are open to public accommodation (such as Brandeis). In 2008, the Americans with Disabilities Act Amendment Act passed, expanding the definition of “disability.” Although we as a country have come a long way in terms of disability rights, there are many areas in which Brandeis’ campus and its culture are not up to par.

Beyond the obvious lack of ADA standards met by campus buildings, the University has also struggled to meet accommodations for students with disabilities. This sends a message to students with disabilities, according to the students that the Justice spoke with, that they’re not welcome here, and that this campus physically and mentally cannot accommodate them. As a part of an investigation into accessibility on Brandeis’ campus, the Justice sat down with both students and administrators to dive into the question of accessibility on campus. Here are their stories.

Ivy Hardy

After a handful of health care professionals recommended that Ivy Hardy ’21 get a service animal for her disabilities, she began the long and grueling process of finding a service dog.

This was at the beginning of the spring 2019 semester, after Hardy had received several new diagnoses related to her mental health. Soon after, she began doing research to find a service animal. Paying for a trained service animal costs thousands of dollars — on top of the cost of the animal itself, the cost of transporting it to campus and other expenses — so Hardy said she had to find a dog she could train herself.

In February of 2019, she found a service dog named Cedar and began the process of figuring out how to integrate him into her life at Brandeis. She went to Student Accessibility Services, which directed her to the Department of Community Living. Hardy recalled that they had her submit a doctor’s note, Cedar’s veterinary records and sign an agreement that spelled out a list of rules and responsibilities for service animals on campus.

On April 7, Cedar arrived at the University from Tennessee. Hardy said she started Cedar off with basic obedience and service training.

Two or three days after Cedar arrived on campus, Hardy was opening the door to her single room in East Quad. As she opened the door, Cedar ran out into the common room, which was unoccupied except for a facilities worker. Hardy said she quickly apologized, but that the facilities worker did not seem bothered by the dog, as he “said hello to Cedar and told [Hardy] what a beautiful dog he was.” Despite the seemingly inconsequential nature of this incident, Hardy said she received an email later that day saying that there had been a complaint that Cedar was running around the common area.

After this incident, Hardy trained Cedar to wait for a command before going through doors. As time went on, Hardy said, Cedar was adjusting well to his new environment and making progress in his training.

Hardy recalled that Cedar was by her side almost all the time. There were only two exceptions. One was for large lecture hall classes, where Cedar could possibly get overwhelmed or cause a disruption. The other was when she was tutoring. The room in which she was assigned to tutor was small, and she said that her students were not comfortable having Cedar, a larger dog, in the room during their sessions. According to Hardy, Cedar was never alone in her single room for more than three hours in a day. This did not violate the agreement she signed, which only says that owners cannot leave their service animals alone in University housing overnight.

Nine days after Cedar arrived on campus, Hardy said she received an email from DCL asking her to come into the office, where she met with then Associate Director of DCL Paris Sanders. In the meeting, Hardy learned that she had to remove Cedar from campus.

“That was a shock,” Hardy recalled. Cedar had only been on campus for a few days, and beyond the email she received after Cedar slipped out the door of her dorm, “there hadn’t been any warning,” Hardy said. She learned in the meeting, however, that Cedar had been barking and students had complained about the noise. One day when he was barking, a DCL team went to check on him in her room. Hardy said that Sanders told her that “Cedar put his paws up on someone in greeting” and that she was “lucky that they were dog people.” Based on this interaction and the barking, DCL determined that Cedar was “out of control” and “couldn’t be allowed on campus anymore,” Hardy said.

Hardy asked if there was anything she could do. She could appeal, Sanders said, but if the appeal failed she had to remove him from campus within six days. Spring break, however, was just three days away. Hardy remembers this meeting as a “devastating three minutes that changed my world.”

After the meeting, Hardy returned to her room and began feeling the symptoms of her disabilities. “Cedar, without even a cue, started performing the tasks that I was training him to do to mitigate my conditions and to help me live my most normal life,” Hardy said. “Probably one of the hardest moments of all was seeing him looking at me and doing exactly what he was supposed to do for me, and knowing that someone had said that this wasn’t okay, that this wasn’t allowed.”

Hardy said she chose not to appeal for Cedar to stay. She had nowhere for him to go during an appeal process, she said, but it was about more than just logistics. “I was also utterly convinced by that sort of decision that I didn’t deserve to have a service animal. … The powers of Brandeis had sort of looked at my situation [and] decided that the inconvenience to other people was far more important than the need for myself.” Hardy also believed at that point that what had happened was her fault, and she decided she would not get another service animal again.

Once she decided not to appeal the decision, Hardy had only a few days to find somewhere for Cedar to go. She first tried to find a place that would board him. When that failed, she traveled to Rhode Island to try to find a foster home, but was unable to find one that was sufficient. Eventually, Hardy had to pay $2,000 to send Cedar back to his foster home in Tennessee. Hardy got to visit Cedar one more time at his foster home before he was adopted.

For months, Hardy said, she avoided discussing what had happened because she found it painful to do so. At the end of March 2020, however, Hardy met with then East and Skyline Area Coordinator Kate Mandel over Zoom to try to find out what had gone wrong. Hardy said that Mandel clarified in the meeting that she was not speaking on behalf of DCL.

In the meeting, Hardy explained in detail what had happened with Cedar. Hardy said that DCL had determined that Cedar was not in the control of the handler. The ADA makes permission to bring a service animal into certain spaces conditional on the animal being well-behaved, but stipulates: “If a service animal behaves in an unacceptable way and the person with a disability does not control the animal, a business or other entity does not have to allow the animal onto its premises. Uncontrolled barking, jumping on other people, or running away from the handler are examples of unacceptable behavior for a service animal.” Cedar had been barking and jumping in Hardy’s room, which she saw as a private space, in which case it would be acceptable for Cedar to bark and jump there. Mandel, however, told Hardy that her room was a semi-private space because DCL has the right to enter her room.

Hardy asked Mandel what the distinction was between a private space as defined by the ADA and her room, and Hardy said Mandel told her that was up to the University. “Brandeis had the discretion to say that my room wasn’t a private space and Cedar had to be under control as though in public at all times when in my locked dorm room,” Hardy said. Hardy told Mandel that throughout the whole process, no one had told her that her room was not a private space.

In a May 20 email to the Justice, Mandel said that while section 9.5 of Student Rights and Responsibilities reserved DCL’s right to entry, “All rooms in our facilities are considered private.” She continued, “A service animal should be with its handler at almost all times. That animal must be in the handler’s control and cannot be disruptive to others.” According to Mandel, DCL handles issues with animal behavior “based on the individual circumstances of the situation.”

Hardy said that Mandel also told her that she had not been required to sign the service animal agreement, despite having been told to sign it. Mandel said in the meeting that she had had the right to refuse, Hardy recalled.

The agreement, which aligns with the ADA’s behavior requirements for service animals, says “The behavior, noise, odor, and waste of the Animal must not exceed reasonable standards, and these factors must not create an unreasonable disruption for residents and Community Living Staff.” It also says that “the Owner must be in full control of the Animal at all times” and that “The Owner is responsible for ensuring that the Approved Animal does not adversely affect the routine activities of the residence hall.”

According to Hardy, before the conversation with Mandel, no one at DCL or elsewhere had ever informed her that signing the agreement was not mandatory. Brandeis’ service animal policy for residential students says, “Once the Housing Accommodation process is complete an agreement will be signed between the Department of Community Living and the student seeking the Service Animal.”

Hardy said that Mandel told her that she should have been better informed about the process and that someone should have told her that her room was not a private space, but that the responsibility is on the student in this case. “When I asked about the financial and emotional damage done by moving Cedar, I was told that I had taken on that risk when I decided to get a service animal,” Hardy said.

“That was obviously an incredibly difficult conversation for me, and again made me feel as though what had happened was my fault, that I hadn’t been, somehow, careful enough, informed enough,” Hardy said. “I don’t know how I could have been more informed than I was, and [Mandel] seems to recognize as well that I was informed as I could reasonably expect to be, but not informed enough to do it right.”

Nora Perlmutter

On June 3, 2019, Nora Perlmutter ’20 was finishing up a grueling rollerblading workout on the Brandeis tennis courts after completing her first day at her summer lab position. “I took a right turn at about 20 mph, and I went down,” Perlmutter said in a Feb. 29 interview with the Justice. Perlmutter broke her ankle and endured numerous surgeries to correct the break; however, she spent her senior year at Brandeis on crutches. And so began her tumultuous, yearlong experience with accessibility at the University that ultimately resulted in a threatened lawsuit, follow-up surgeries and distrust toward the administration.

Following her break, Perlmutter spoke with the Student Accessibility Services and was placed on a list of students with limited mobility. She was promised access to the accessibility van, but she constantly ran into difficulties with transportation. Perlmutter was not allowed to park close to the upper parking lot by the science complex due to overcrowding, and as a result she struggled to get to the lab to complete her work.

Despite nearly all of the housing options and buildings on campus generally failing to meet ADA standards, Perlmutter did not struggle with housing due to her disability. She lived off campus over the summer and was “lucky enough to get pulled into a Ridgewood” for the start of the semester long before she broke her ankle. Since the main accessible housing options are Ridgewood and Village, she decided to remain in her Ridgewood.

Where Perlmutter struggled to receive support and accommodations was with the transportation options around campus. “The accessibility van was at best inconsistent and unreliable. … More than half the time it was late or didn’t show up at all,” Perlmutter said.

Due to inconsistencies with the van, Perlmutter was constantly late to class. It even got to the point where she scheduled pickups and drop offs 20-30 minutes before she actually needed to be somewhere because she expected drivers to be late or not show up at all. Often, Perlmutter had to “just suck it up and walk.”

Perlmutter also explained that students have to fill out a form explaining when they need to be picked up and dropped off on Sunday nights, scheduling for the entire week.

“Science time is not the same time as real time, as I’ve learned,” Perlmutter said. It was often difficult for her to anticipate her work schedule and to coordinate meals and social time with friends.

“As part of the [Accessible Transportation] driver's On Call duties, passengers may text/call the driver on shift and request a pickup, given that there are no other van reservations. The driver must always be no more [than] five minutes away from the parked van for such occasions. Students are encouraged to provide as much information as soon as possible to facilitate efficient transport requests,” the Director of Public Safety (who oversees accessibility van operations) Ed Callahan said in a May 20 email to the Justice.

Students can request same day reservations for the accessibility van, but they have to text individual drivers who often do not respond to messages because they are driving, she explained. Perlmutter continued that the accessibility van is almost entirely student run, which leads to problems with scheduling. She did not use the accessibility van the entire first week of the spring semester because she “knew that with students getting back, there would be no work schedule, there would be chaos and there’s no way they’d get me, so I didn’t even bother.”

“It’s a bad system. … I don’t fault the drivers or the supervisor [who is also a student]. A lot of drivers are really friendly and working way too many shifts,” Perlmutter said. “I really felt conflicted about telling anyone about my problems.”

During the fall 2019 semester, Perlmutter had two classes that met 10 minutes apart — one in the humanities quad and one in the science complex. She reached out to the accessibility van, and they said that since she would need to travel between 4:50 and 5:00 p.m., which is a highly trafficked time, that they wouldn’t be able to bring her between her classes. She reached out to SAS and asked that they either provide transportation or move her class, and the office claimed there was nothing they could do.

Perlmutter felt that her needs weren’t being heard or listened to by anyone, so she emailed Dean of Students Jamele Adams. She never heard back from Adams, but the following day she was notified that one of her classes had been moved and both were now in the science complex. “I know that it could be done, Accessibility just didn’t do it.”

Because the accessibility van was unreliable, Perlmutter often had to walk to classes and engagements to the point that she required a second surgery to correct the damage that the extra strain put on her break. She learned of this surgery in early November and realized that its four to six week recovery time would most likely interfere with her final exams. Perlmutter immediately contacted the Registrar’s Office and her professors about taking her finals early. “Both of my professors were willing to work with me, but hands were tied by the University.” They offered to let her take finals in January, but she explained that “that’s worse. I’m still going to be on pain medicines for the entirety of the break. I’m not going to be able to study regardless of whether it’s a week after my surgery or a month after my surgery,” to which the Registrar responded that they do not under any circumstances allow students to take finals early.

Interim Director of SAS Scott Lapinski said in a May 19 interview that “it’s certainly possible to move an exam early … [and that when reviewing a request, SAS] look[s] at each request individually.”

Perlmutter took her finals on pain killers and “totally failed them.”

At this point, Perlmutter had had enough. She was tired of the administration’s carelessness towards her situation and frustrated with the fact that she’d have to endure another surgery and its recovery due to the University’s failure to meet her needs.

Perlmutter sent an email to Adams at the beginning of the spring semester threatening to file a lawsuit if conditions didn’t change. “I pay thousands of dollars a year to come here. All I want is to be able to get to my classes on time without causing more damage to my foot,” she said.

Her cousin, who is a personal injury attorney, explained that the University had been violating her ADA rights for a very long time and that she needed to take action. “I really did love this University until last semester … [and now I] can’t wait to be out of here,” Perlmutter said.

Then, the apology emails started to roll in. Perlmutter explained that she received many emails that addressed her complaints. “This made me upset for a lot of reasons because it made me feel like I was in trouble and made me feel like I was getting other people in trouble and that my opinion was an unwanted voice on campus and that my needs weren’t valid,” Perlmutter said. “And it also hurt that I needed to threaten a lawsuit for them to actually care,” she added.

Since she threatened to file the lawsuit, the van has been more consistent and on time, Perlmutter said. She still has to book her ride appointments in advance, but she does not worry about the van failing to show up like she previously did. However, Perlmutter expects the van operations to return to their normal unreliability after she graduates.

“I imagine they are only helping me because I threatened a lawsuit, and I know other students who are forced to also utilize the accessibility vans — no one wants to use the accessibility van — and they say it’s still inconsistent, so I imagine they have a red star next to my name that is like ‘please don’t be late for this person’ which also doesn’t feel good,” Perlmutter said.

Perlmutter said she thinks the conversation about accessibility on campus is “incredibly lacking.”

“A lot of the students are aware that a lot of the buildings aren’t accessible and that the hills themselves are not accessible, [but] I think there are misconceptions within the offices themselves that they are doing all that they can and that they are helping students,” Perlmutter said. “Because from what I’ve seen, they’re not.”

Perlmutter stressed that the administration must be more receptive and act on student complaints. Brandeis “tells me I’m not wanted here, I’m not valued and that maybe even I’m less of a person because I can’t walk to my classes on my own and I’m not like the hundreds of other students who don’t need [extra help],” Perlmutter said. “…It felt to me that I was inconveniencing everyone at Brandeis, and it’s not even that my accessibility is that severe. I’m just on crutches.”

Perlmutter continued, “We’re not complaining because we want to. It doesn’t feel good to complain. It makes me feel unwanted and like a burden and it’s not the kind of attention I like having. … No one works for change because they want it. It’s because they need it.”

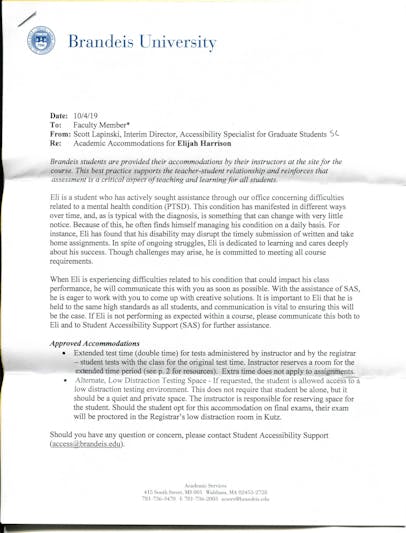

Eli Harrison

In the summer of 2018, former Brandeis student Eli Harrison decided he was ready to reenroll at Brandeis after taking a health leave of absence related to his disability, post-traumatic stress disorder. Two summers later, the Committee on Academic Standing informed him that he was required to withdraw from the University.

“Everyone thinks they’re doing me a favor by saying, ‘Change takes time, just be patient,’” Harrison told the Justice in an August 4 interview. “Meanwhile I’ve just gotten kicked out of the university. OEO told me that, my advisers told me that, Student Accessibility Support told me that, the provost told me that. Everyone.” The Justice spoke with Harrison on multiple occasions to try to piece together what exactly went wrong during those two years.

Dean of Academic Services Erika Smith, who oversees the Health Leave of Absence Committee, told the Justice in a May 19 interview that any student who leaves the University is reviewed by the HLOA Committee and COAS upon their return. The HLOA, Smith said, is made up of health professionals, and they consult Brandeis Counseling Center faculty when it is relevant to the case. Students can also submit appeals, she said. This is the process that Harrison began during the summer of 2018.

Harrison told the Justice that he received an email from his academic advisor, Katy McLaughlin, on Aug. 10, 2018 saying that the HLOA Committee had granted him health approval. At that point, he was just waiting on the Committee on Academic Standing’s decision. McLaughlin told him in an email that he would hear from the committee on August 20.

In the meantime, Harrison said, he received a call from his non-Brandeis-affiliated therapist, Dr. Joy Beckwith, informing him that Dr. Joy von Steiger, Director of the Brandeis Counseling Center, had told her that she thought Harrison should not return to Brandeis in the fall as planned. As the deadline to register for housing and classes drew nearer, Harrison decided to fly from his hometown of Atlanta, GA to the University to try to sort the situation out in person.

On Aug. 21, Harrison arrived in Boston. That day, he also received an email from Smith that von Steiger had overturned the HLOA Committees decision and he would have to wait until the spring semester to return to Brandeis. She wrote, “While the Health Leave of Absence (HLOA) Committee reviewed your request to move your petition for return from your leave forward to the Committee on Academic Standing, and initially approved it to go forward, additional information from your healthcare provider has caused that decision to be reversed.”

The next day, Harrison went to the BCC to learn more about von Steiger’s decision. He waited until she came into the building, at which they had an impromptu meeting.

In the meeting, von Steiger told Harrison she made her decision because she believed he was “incapable of functioning without the constant guidance and supervision of [his] mother,” Harrison recalled. Harrison was shocked by her “horribly harmful words,” finding her comment to be “deeply painful” and untrue. “I was doing all of it on my own,” he said, referring to the fact that he had flown out to Massachusetts to take meetings and advocate for himself in an attempt to reenroll. At the time, he said, he was “ready to sleep on the floor in a sleeping bag for as long as it would take for [him] to get established at this school,” so he found the claim that he needed his mother’s help to be inaccurate.

Von Steiger told Harrison that she came to her conclusion from talking to his therapist. “I left feeling shaken and empty,” Harrison recalled.

Harrison then spoke to his therapist on the phone about what happened, and she insisted that she did not tell von Steiger that Harrison needed his mother’s supervision. Later that day, Harrison emailed von Steiger about setting up a phone call with his therapist to sort out the mismatch in information. Von Steiger did not respond to his email.

On Friday, Harrison met with Smith, as she oversees Academic Services, the department that handles reenrollment. He told her everything that had happened, and she said that in her 10 years of handling HLOA reenrollment cases, she had never seen a case where a HLOA Committee decision was overturned in this manner. She also told him that there was nothing she could do for him.

After this meeting, Harrison said he left Brandeis and fell into a “deep depression.” By that point, Harrison had already quit his job at home in anticipation of reenrolling, since the reversal of the decision came just one week before classes were set to begin on Aug. 29. His trust with his therapist was damaged, he said, and he had to convince his mother to let him reenroll at Brandeis again. The whole experience, he said, “caused extreme detriment to [his] health.”

Harrison said he felt like the University had taken advantage of his respect for and faith in the institution. “I’m tired of this. I’m tired of being manipulated and used. I’m tired of having my goodwill used as an excuse to not pay attention to me,” he said.

Reenrollment at Brandeis after a HLOA requires that the student submit a personal statement, which Harrison did on October 31, 2018 in hopes of returning to campus that spring. In his personal statement, Harrison explained the work he had been doing to improve his health, demonstrating that he was ready to come back to school. Regarding his experience with the reenrollment process at the end of August, he wrote, “I came to Brandeis to address with you these concerns which I know so intimately, but also to share my hard-won strengths and abilities. My intent was [to] advocate on my own behalf in a thoughtful, respectful and conciliatory manner. My actions were not so received. I was deeply saddened by that fact.” Looking back on his personal statement, Harrison said he felt that he held back the extent to which the University’s actions affected him “I spared the University the truth so that I might get back in,” he said.

Harrison returned to Brandeis for the spring 2019 semester. Immediately, he ran into more problems related to his disability.

After a particularly difficult episode related to his disability, Harrison sought out assistance from Beth Rodgers-Kay, the SAS director at the time. Harrison explained that after four days of unexpectedly being confined to his room because of his disability, he sought out permission from a professor to receive extensions on assignments. Harrison said that Rodgers-Kay told him there was nothing she could do because SAS does not give extensions, and that he should plan ahead in case something similar were to happen in the future. Harrison explained that he could not plan ahead because he could not predict how his disability would manifest. She suggested he use the writing center and tutoring, services that are available to all students regardless of ability.

Harrison described how the conversation culminated: “I asked her, ‘So are you saying what I need to do is accommodate myself?’ And she said, ‘Yes, you need to accommodate yourself.’ This was the head of Student Accessibility Services telling a student with a documented disability that they needed to accommodate themselves.”

Harrison described his dissatisfaction with the overall culture of accessibility at Brandeis. He explained that the accommodations Brandeis offers do not always align with students’ needs and that accommodation letters from SAS often do not require professors to do anything for the student. For example, Harrison said he wished he could have had extensions for some of his assignments because of his disability, but SAS could only offer him extended time on tests, which he did not need because it did not help with his disability. Harrison said he felt like the only way to get professors to take his disability seriously and grant him the extensions he needed was to divulge personal and sometimes traumatic information, which he said is emotionally draining and sometimes not even effective. He described this as a “put-on-you culture.”

At the end of the fall 2019 semester, Harrison filed a complaint with the Office of Equal Opportunity about his reenrollment experience. A report by the OEO with the results of the investigation, a copy of which was obtained by the Justice, found that the HLOA Committee “did not materially deviate from the HLOA return process in this case by reversing the original decision of the Committee.”

According to the report, the investigator, Amy Condon, came to this conclusion after speaking with von Steiger, Smith, McLaughlin and Director of Academic Advising Brian Koslowski, and after reviewing a number of relevant documents.

Von Steiger said that Beckwith told her in August of 2018 that “she had concerns” about Harrison’s reenrollment, the report said, explaining that Beckwith had told von Steiger that Harrison was “not yet fully independent” and “needed more accountability” when his mother or Beckwith were not available to help him. “Based on the additional information shared by Dr. Beckwith, on Aug. 21, 2018, Dean Smith emailed to inform you that the original decision approving your petition was reversed,” the report said.

Harrison told the Justice on Sept. 10 that he felt that the results of the investigation misconstrued Beckwith’s intent and did not align with his or Beckwith’s recollection of how the events transpired.

Before his case concluded, however, Harrison submitted a request to COAS to halt the review of his academic standing that would happen at the end of the spring 2020 semester. He wrote in a June 17 email to Smith and COAS, “In light of ongoing deliberations and in acknowledgment of the good faith effort of all parties, I ask for a temporary stay, an injunction, on alterations to and rulings on academic status regarding myself. … The intent here is to thoroughly address serious accusations of misconduct levied at Brandeis University and its officers.” Harrison wanted his OEO case completed before the committee reviewed his grades.

He petitioned COAS to acknowledge that Brandeis’ handling of his disability needs negatively affected his academic performance.

On June 22, Smith responded to Harrison’s email, telling him that COAS had rejected his request and had instead recommended that he “reflect on [his] own agency in engaging the resources available to [him] as a student at Brandeis. The committee was struck that [Harrison] had worked with four different advisors in Academic Services, who they know to be effective in supporting many other students over many years in addition to myself and staff in Student Accessibility Support.” Harrison told the Justice that he had, in fact, had only three advisers — his first adviser, McLaughlin, told him he should transfer to Katie Dunn, who transferred him again when she went on maternity leave. Harrison pointed out that even if he had worked with four different advisers, that would have reflected COAS’s recommendation that he engage with Brandeis resources in order to meet his disability needs.

Smith’s email also said that COAS recommended that when he petition the committee in July, he “provide more of [his] own personal narrative.” Harrison told the Justice that he felt this statement asserted that COAS “deserve[s] intimate, personal details about your life and your struggles in order to make our decision.”

Harrison reached out to Dean of Arts and Sciences Dorothy Hodgson about his concerns with the committee’s response, as she oversees COAS appeals. He asked to meet with her to discuss this before the committee would meet to discuss his case on July 30. She wrote back on July 28, “I am sorry that you have concerns about COAS. My experience with them has been quite the opposite - I have found their deliberations to be compassionate, thoughtful, and attentive to the specific situation of each student. I also think that the process in place is fair and equitable.”

In a Sept. 11 email to the Justice, Hodgson explained that when deciding COAS appeals, depending on the case, she will ask Smith to provide her with an overview of the COAS committee meeting, consult with Registrar Mark Hewitt about past practices and speak with the student involved.

In an Aug. 4 interview with the Justice, Harrison said that COAS had told him he was required to withdraw from Brandeis.

Harrison told the Justice that he wished he could have been at the committee meetings, both to defend himself and to dispute inaccuracies like the one about his alleged and disproven adviser-hopping. He said that there was no recording or accessible minutes of these meetings, and his multiple requests to be at these meetings were denied. “I couldn't speak for myself in the moment and address the concerns that they were raising, which I happily would have done and had answers for each and every one of them,” Harrison said. “And if those answers hadn’t been sufficient, then … that’s their right.”

According to Harrison, the reason he was not allowed to speak at his COAS appeal was that it wouldn’t be fair to other students in his position. Harrison had a suggestion that Brandeis did not choose to implement: “Give all students the opportunity to be present for a hearing.”

If Harrison completes his undergraduate degree elsewhere, he will be at least 28 upon graduation. Harrison said that with his current GPA, he would struggle to find another school to admit him. He has no plans to enroll in any college or university at this time. “It seems like it’s too late for me. I really, really hope that these things get addressed soon so that other students don’t have to feel this way, and yet, I don’t see any way that that’s going to happen,” Harrison concluded.

***

Since COVID-19 has caused much of life to transition into an online format, people with disabilities have had the opportunity to participate in a myriad of events that they may have had difficulty accessing before. In this way, the pandemic has in some ways evened the playing field in terms of access for students with disabilities; however, more starkly, COVID-19 has highlighted the growing divide in internet access, rendering certain activities for those without high-quality internet access nearly impossible.

While it is true that all students were theoretically able to attend classes, events and office hours without having to rely on the fickle Accessibility Van, or without requiring special parking options or other accommodations (such as service animals), in the transition to online learning last semester, all of these activities were entirely dependent upon internet and technology, which are not accessible for all. There are many residential students who rely on Brandeis’ internet and other technology resources that may not be available to them in the same capacity at home.

For students who remained on campus during the summer, they did not have access to transportation services around campus, according to Callahan.

Even now, as some students have returned to campus and others have decided to remain at home, accessibility is impacted. Imuno-compromised, at-risk individuals are impacted by COVID-19 at higher rates and face a higher rate of mortality or serious complications, according to the CDC. Therefore, access — in some cases — has literally determined whether or not students have chosen to return to campus.

This also brings up the question of timezone. According to Global Brandeis, in the 2018-2019 academic year, international students made up approximately 20% of the undergraduate population and 47% of the graduate population. Many of these students are now remote and are facing the unique situation of taking their classes in the late hours of the night.

The pandemic has also further stalled the search for a new Director of SAS following the unexpected retirement of Rodgers-Kay in August 2019. SAS is currently headed by interim director Lapinski. Academic Services selected finalists for a permanent director in the fall of 2019, but the position remains unfilled.

“I want to sit down with a number of campus partners and sort of assess where we are right now and think about the niche that we want the director to fill … but we may be in a different place right now given the shifts of the pandemic,” Smith said in a May 19 interview with the Justice.

She explained that the timeline is unknown, but that the search committee has a “strong commitment … to finding the right person, not just hiring a candidate. ”

In terms of higher education at Brandeis and many other institutions, students with disabilities face obstacles that other students don’t. The pandemic has only served to amplify this inequality.

“We are students at this school,” Harrison said. “We have earned the right to be here.”

Joy von Steiger declined to comment on the Health Leave of Absence Process, redirecting the Justice to Erika Smith, who oversees the HLOA Committee.

—Editor’s Note: Justice Editor Cameron Cushing ’23 is a Community Advisor for DCL. He did not contribute to or edit this article.

Please note All comments are eligible for publication in The Justice.