In the fall, anonymous users Zoom-bomb virtual panel about Uyghur Muslims

One of the panelists, Rayhan Asat, spoke with the Justice about her experience on the Zoom call.

In November, anonymous users interrupted a virtual panel discussing the oppression of the Uyghurs Muslim minority group in Xinjiang, China. One user played the Chinese national anthem and others used the annotation function of Zoom to write “Bullshit” and “Fake News” across the screen. A joint statement from the event sponsors said that just before the Nov. 13 event they were notified about “threatening emails from members of the Chinese Students and Scholars Association” urging the University to cancel the panel. The emails, according to the sponsors' statement, were sent to the President’s Office, the International Students and Scholars Office and the Office of Diversity, Equity & Inclusion.

Leon Grinis ’22, organizer of the event and recipient of the Maurice J. and Fay B. Karpf and Ari Hahn Peace Award, told the Justice in a Jan. 31 email that he was unable to remove the annotations on the screen, mute the disruptive members or unmute himself because his Zoom account was not linked with his Brandeis account at the time of the event, and the meeting only allowed for one meeting host at a time (the host was the only user who could perform such functions during the event). Because his account was not linked with Brandeis, Grinis explained, Information Technology Services was unable to identify those responsible for the attack, including whether they were Brandeis students.

“I want to clarify that the majority of attendees were more than respectful and engaged in peaceful and interesting discussions with members of the panel,” Grinis wrote. “It was due to an unknown number of individuals who had previously, purposefully colluded and agreed to, on social media platforms such as WeChat, to petition to several university organizations, including President Liebowitz, to hinder, prevent, and sabotage the event’s launch and unfolding.”

The Uyghur people are a Muslim, Turcic-speaking ethnic minority living predominantly in Xinjiang, a historically contested region that became part of the People’s Republic of China in 1949. In 1955, it was designated as an autonomous region, a Chinese administrative division created to give more legislative rights to provinces with a relatively high population of ethnic minorities. Since 2017, one million of the 11 million Uyghurs in China have been detained in over 85 camps in Xinjiang, according to an article in PBS NewsHour. Although the Chinese government previously claimed these camps did not exist, they now acknowledge them, calling them “vocational education and training centers” with the purpose of “prevent[ing] the breeding and spread of terrorism and religious extremism,” according to a paper published by the State Council Information Office. Testimonies reveal that Uyghurs were interrogated and brutalized while they were detained at these camps, per the PBS NewsHour article. The Chinese government has also passed laws outlawing the veils and long beards that Uyghur people frequently don.

According to the Brandeis events calendar, the panel — sponsored by the International Center for Ethics, Justice and Public Life and the Maurice J. and Fay B. Karpf and Ari Hahn Peace Awards — featured experts, professors and Uyghurs and was intended to “bring focus towards improving China’s treatments towards its ethnic minorities.” One of the panelists was Rayhan Asat, a Uyghur attorney who grew up in China but now lives and practices law in the United States. She spoke to the Justice on Dec. 14 about the panel, which Asat said she did not expect to be disrupted. Before the event, Asat said she was notified of the emails asking the University to cancel the event, at which point she became “uncomfortable.”

When Asat joined the Zoom meeting at the beginning of the panel, some participants had their profile pictures set as images of prominent Chinese leaders, such as Xi Jinping, the current Chinese president. “I was afraid at that moment,” Asat recalled. “I felt just horrible.” She said she saw this action as a way of instilling fear and silence. While another panelist was speaking, Asat said, one user played the Chinese national anthem for 20 to 30 seconds. That user was removed from the Zoom meeting.

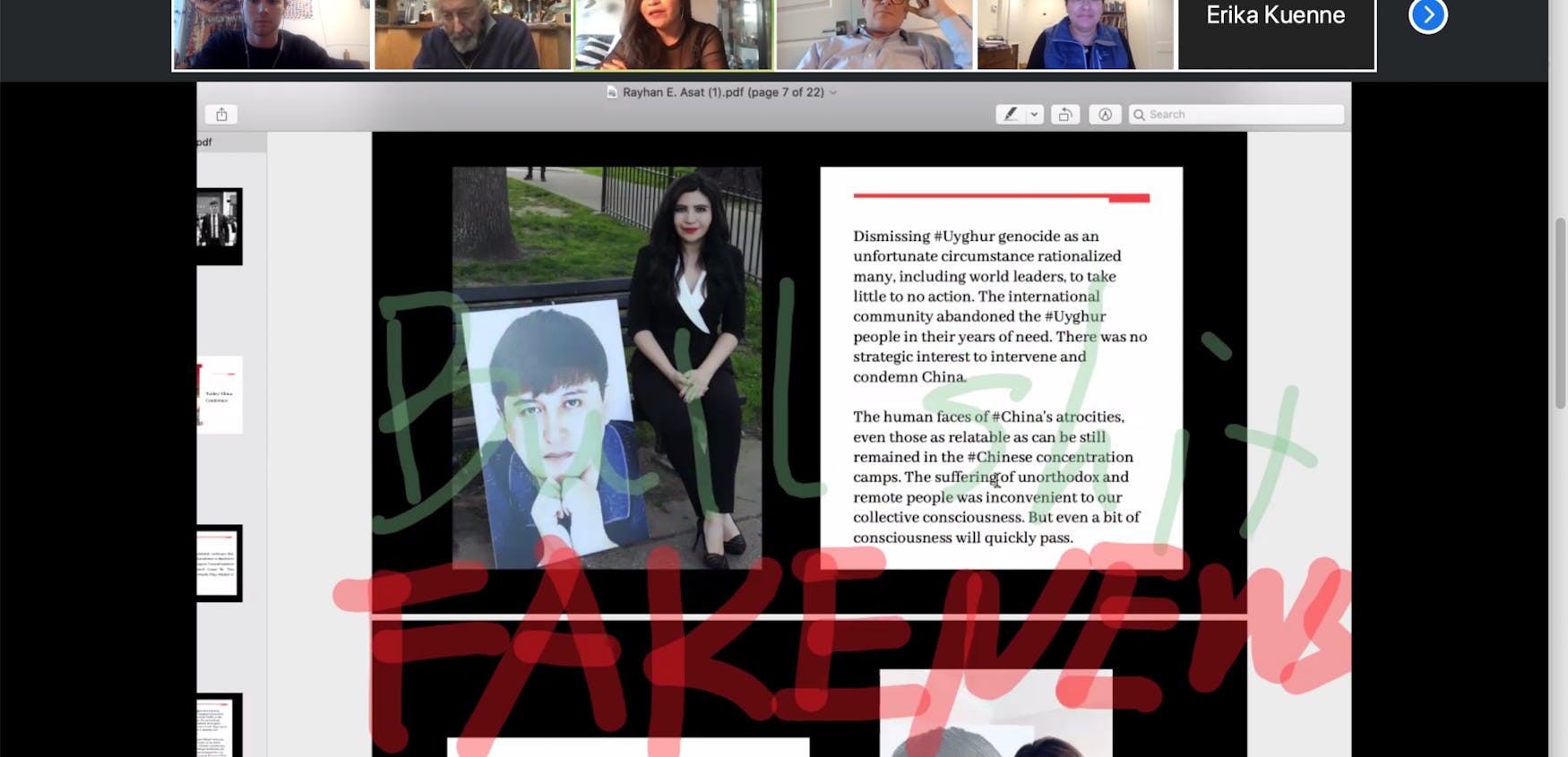

For almost five years now, Asat’s brother has been detained in a Uyghur concentration camp in China. Asat began her presentation by talking about him and showing a slideshow of pictures of him. One of the users used the annotation function to write “SOB” across a photograph of her brother, but Asat said she tried not to be distracted by it as she presented. She explained in her presentation and to the Justice that she and her brother had been model citizens in China, but that even that was not enough for him to avoid government detention.

Grinis wrote in his email to the Justice that although he and others held sticky notes up to the camera to try to tell Asat how to to remove the annotations, “since she was focused on persevering and presenting, ultimately the insults remained on screen and continued to grow,” including the words “Bullshit” and “Fake News” written across more images of her brother.

“They’re just like erasing him as if he’s nobody,” Asat said. “That moment was just incredibly painful. And I think that’s exactly how it happened. … They just forcibly disappeared him. Like he just vanished.”

Asat said that despite the strong emotions she was feeling in reaction to the disturbance, she continued her presentation. “I’m an attorney and I’m professional,” she said. “I cannot stoop to somebody else’s level, but just maintain my integrity and professionalism.” Although she managed to remain composed during the panel, Asat told the Justice that for days after the event, she had nightmares.

After Asat’s presentation, the moderator made an announcement that these disturbances were unacceptable, and then commended Asat for maintaining professionalism throughout the incident.

The moderator then moved on to the Q&A section of the event. The first participant that was called on did not have a question, but rather read a prepared statement in response to the panel. Asat said this statement claimed that everything that had been covered during the panel was untrue and used language associated with the Chinese Communist Party. Another participant, before asking his question, said, “Some of the panelists are so emotional today,” Asat recalled, a comment which she said she felt was sexist. “I’m talking about my brother being detained and not being able to talk to him for more than four years and not knowing whether he’s alive. Like, I mean, I think I should be allowed to be … emotional,” she told the Justice.

Although the panel faced numerous disruptions, some expressed their support for Asat during and after the event. She recalled that one student, before asking his question, also apologized for the behavior of other participants. After the event, a number of Brandeis students emailed her apologizing on behalf of the other participants and saying that, aside from the disruption, the event was well done. Asat also received emails from three different students telling her that they had seen Brandeis students planning this Zoom-bombing on WeChat. The students apologized for not having the courage to try to stop the disruption of the panel, Asat said. A staff member from the ODEI also reached out to her after the event, she said.

Tensions between the United States and China have continued to escalate in recent months, as both the Trump and Biden administrations have used the term “genocide” to describe the CCP’s policies over the Xinjiang region. Both nations have placed sanctions on each others’ state officials, per a Jan. 20 Bloomberg article.

Asat specified that her remarks during the panel had not been critical of the CCP. “I didn’t start off by accusing the Chinese government of anything. I just started off by telling a story about my brother [and] who he is. It’s nothing controversial,” Asat said. During her presentation, Asat had also talked about her work to improve relations between China and Turkey, efforts that her brother had been proud of. “Had I not believed that [the] Chinese government could be [a] force for good, why would I even engage in those bilateral relationships, helping China’s image … worldwide?” she said.

Asat speaks regularly on the topic of Uyghur oppression in China at universities across the country, at conferences and on television, but has never experienced backlash or disruption like she did at the panel in November. “Talking about this experience always makes me feel so uncomfortable and just brings back this very dark memory,” she said. “I could be in those camps if I returned [to China].”

After the event, the event sponsors wrote a statement — provided to the Justice by Professor Melissa Stimell (LGLS) — affirming Brandeis’ commitment to “freedom of expression and civility of discourse as fundamental educational cornerstones.” The statement explained that the Maurice J. and Fay B. Karpf and Ari Hahn Peace Award allocates funds for Brandeis student projects that promote peace and coexistence. Grinis received the award funding in fall 2020 to host this panel. “The hope for this panel was to educate the Brandeis community about the situation in Xinjiang from an objective and non-politicized perspective,” the statement said. “It is our hope that we can create a space within the University for safe and objective discussion of this and other topics that are often fraught with intense emotions and misunderstandings.”

Please note All comments are eligible for publication in The Justice.