'Elantris': A tale of magic, political intrigue and religious conflict

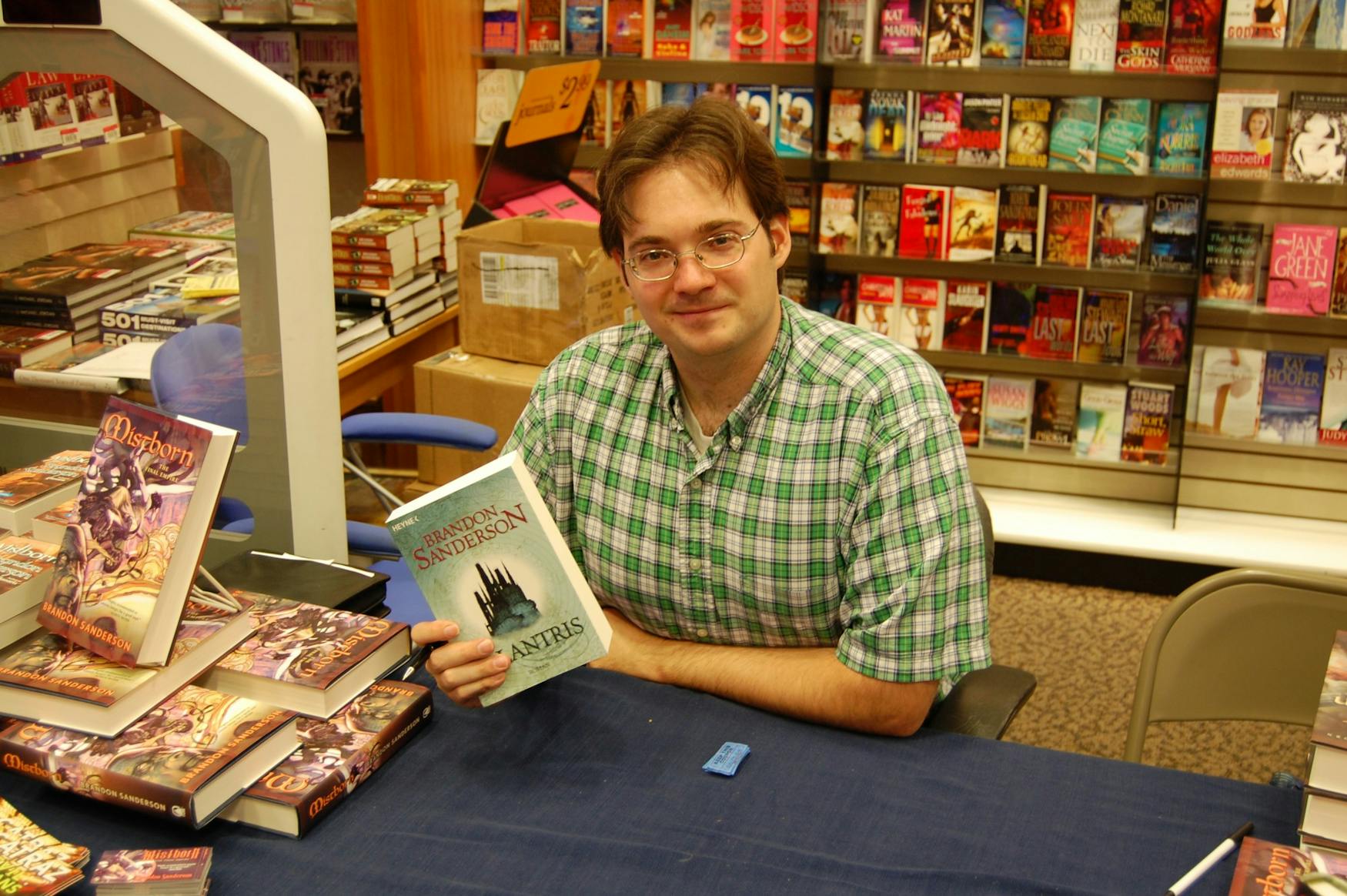

“Elantris” by Brandon Sanderson is a high-fantasy standalone novel about magic gone awry, political intrigue and religious conflict. I decided to read it because I read Sanderson’s “Mistborn” trilogy and enjoyed it enough to check out his other books. Also, my library had the Graphic Audio audiobook, which has a full cast, music and sound effects, and I had been wanting to listen to one of their productions. While it did not become my new favorite book, I enjoyed the intricate plot and worldbuilding.

At the start of the book, Raoden, Crown Prince of Arelon, is about to marry Sarene, Princess of Teod, to ally the last two countries that adhere to their religion, Shu-Korath. However, before Sarene arrives, Raoden is taken by the Shaod, a mystical random transformation whose targets become the cursed undead and are exiled to the slime-covered city of Elantris. Thus, Serene arrives in Arelon to discover that she is a widow and an honorary member of the royal family. Alone and in a foreign country, she uses her newfound status and free time to counter the machinations of Hrathen, a priest of Shu-Dereth. Hrathen was sent to convert the Arelish people, lest they be slaughtered as heretics by the Fjordell Empire in three months time. What follows is lots of political intrigue, combined with dueling religions and a quest to understand why Elantrian magic has stopped working.

One of the best things about “Elantris” is its imaginative and sophisticated worldbuilding. Featuring the politics and cultures of at least three different societies, it is exquisitely detailed, yet never becomes overwhelming. The aftershocks of Arelon’s revolution and subsequent capitalism-meets-absolute-monarchy political system felt very plausible, while Fjordell’s evil empire had enough characterization to avoid becoming a simple caricature. Even the briefly-seen Teod, Sarene's homeland, manages to avoid blandness as a not-quite-fantastical-England. Additionally, the magic system perfectly walks the balance between being explained and being spelled out too much, which could subsequently destroy the wonder of it. While it is extremely complex, Sanderson clearly defines the magic’s rules and limitations.

One of the core plot threads of the book is the religious-turned-political battle between the followers of Shu-Korath and Shu-Dereth. Although religious conflict provides an external motivator for plot events, the story never descends into considering one religion pure good and the other pure evil. While the reader is inclined to think of Shu-Korath as the “better” religion, it is only because that is the religion the protagonists follow. Meanwhile, it is abundantly clear that Shu-Dereth itself has good beliefs, but is corrupted by the people who run it. Neither of them are obvious counterparts to religions here on Earth and instead have distinct rituals and beliefs of their own. It is a pleasant addition that prevents the story from becoming too moralizing.

However, for all that I liked about “Elantris,” I never found myself getting “sucked into” the story. While I was reading, it felt like I was watching what was happening from afar rather than actually becoming a part of the story. I found this disappointing given how “Elantris” is an epic high-fantasy novel with fantastic worldbuilding and multiple plot threads that intricately weave together. These types of books can be extremely engrossing, but this one lacked that quality. I’m not sure what caused it, perhaps the prose, but it dampened my enjoyment of the book.

In conclusion, while it had its flaws, I enjoyed “Elantris” due to its worldbuilding, political-religious conflict and how cleverly the characters scheme to achieve their end goals.

Please note All comments are eligible for publication in The Justice.