Art lecture: the intersection of tradition and invention in Japanese architecture

On April 29, Professor Aida Wong hosted a lecture with Dr. Robert C. Anderson on the topic of Japanese architecture as part of her course, “The Art of Japan,” and the Brandeis Leonard Bernstein Festival of the Creative Arts. With the focus on three contemporary Japanese architects, Anderson took the audience on a virtual aesthetic tour, introduced Japanese aesthetic principles and tracked the connective threads of Japanese architectural forms across time.

The lecture opened with a brief discussion on the aesthetics of spatial expression. Japanese architects are attentive to the symbiotic relationship between architecture and nature. According to Anderson, man-made buildings are never intended to surpass or conquer nature, but instead coexist with it in profound harmony. Anderson introduced a wide range of Japanese traditional architectural elements, among which was the most common structure, the Japanese screen: a flexible device to divide and define the space. Common types of screens include the byōbu (“wind wall” screen) and fusuma (painted screen). These screens not only enclose the interior but also create seamless transitions to the exterior realm. A typical Japanese screen consists of a wooden frame filled with translucent paper. Throughout time, screens have been adapted into a variety of forms and became an important design element in modern architecture. Another important element in traditional architecture is tatami, or woven straw mats. Tatami serves not only as a flooring material but also as the organizing principle of spatial design. This can be seen, for instance, in the layout of the Katsura Palace in which the dimensions of rooms are defined and measured by the number of tatami mats.

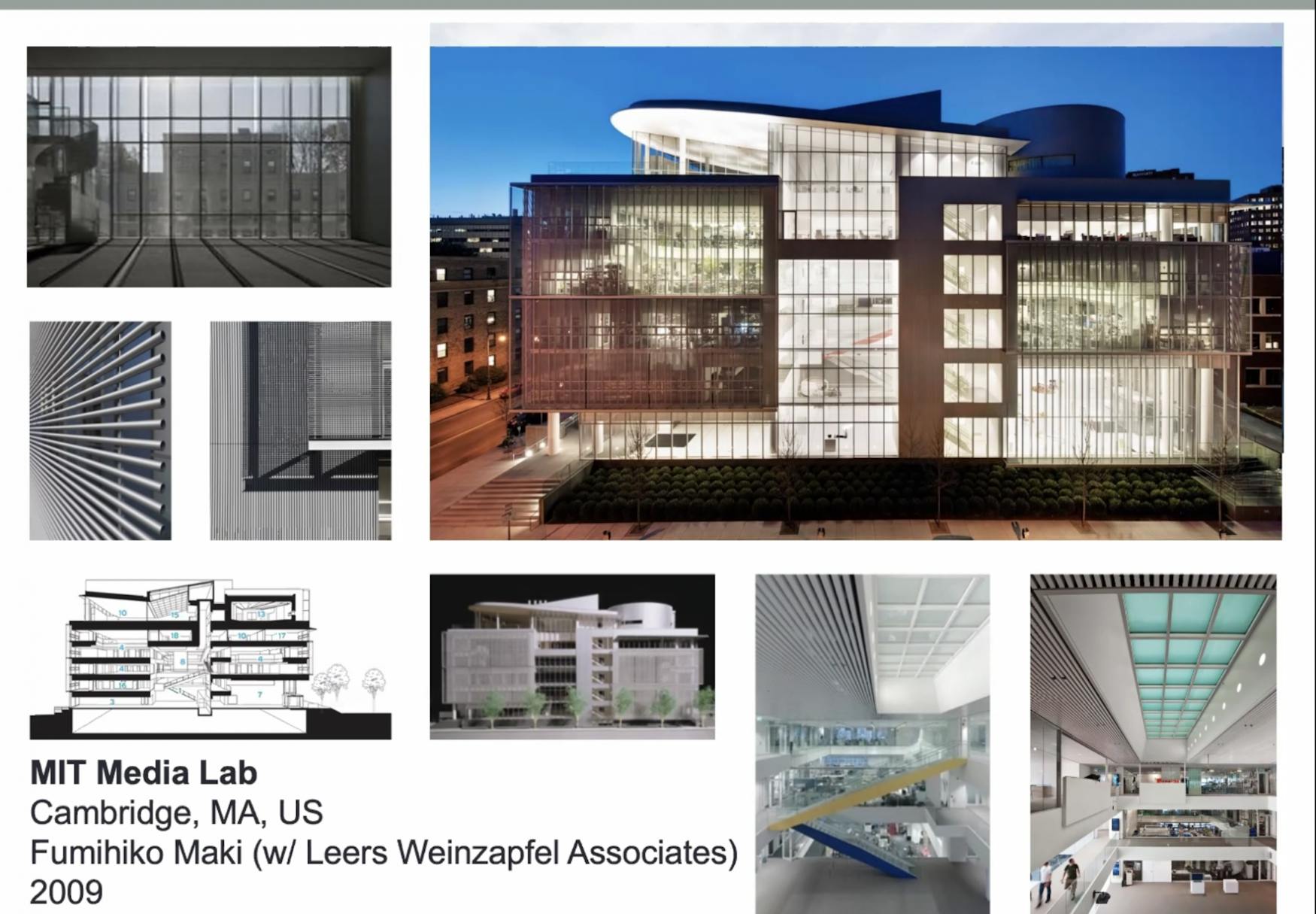

After a detailed explanation of Japanese architectural tradition, Anderson demonstrated how traditional structures had been translated into the modern architectural language. After WWII, Japanese architecture adopted influences from Western art and culture to catch up with international trends of modernization. Rather than imitating the Western notion of architecture, Japanese architects actively sought to establish their own identity in the international arena. They looked back at their traditional architectural forms in an attempt to figure out the essential question of what constitutes the Japanese-ness of their architecture. One of the prominent architects in this era is Fumihiko Maki. Maki was interested in Japanese traditional architectural elements, which could be found in his design of the MIT Media Lab in Cambridge. The building was a response to the growing demand of students and faculty for expanding the Wiesner Building, the Media Lab’s original home. To enhance the social connectivity and collaborative creativity, Maki adapted the cube structure from the Wiesner Building to create new open laboratory space while maintaining the visual connection with the form of the old media building. Light is an important element for the working environment in the Media Lab and to prevent the excessive pouring of natural sunlight while efficiently utilizing it for the sake of energy-preservation, Maki adopted the Japanese screening technique, creating a steel-frame structural grida and wrapping around the exterior architecture. However, Maki does not conceive his screens as pure energy-saving devices but also as an embodiment of Japanese social, cultural and artistic concepts. Beyond adapting the traditional structure, Maki also sticks with traditional Japanese reverence for natural life. In his project, the Hillside Terrace Complex, in Tokyo, he carefully balanced the urban area with wooded sites, fostering humans’ harmony with nature even in the busy modern capital.

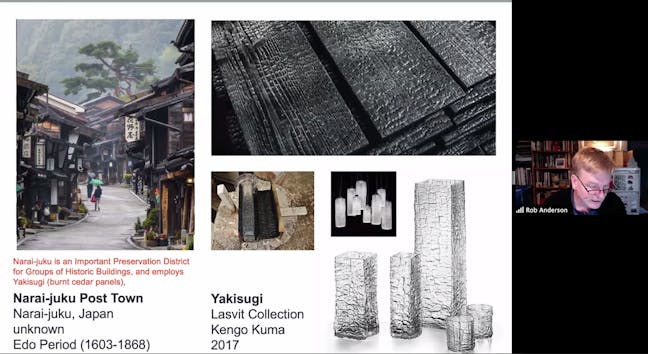

After the discussion of Maki’s works, Anderson introduced us to the ingenious projects by architect Kengo Kuma, who aims to recover Japanese tradition and reinterpret it in the contemporary world. Among the variety of Kuma’s architectural projects he introduced, Anderson identified the Casa Wabi Arts Chicken Coop as one of his favorite and most humorous works by Kuma. In the project, Kuma creatively establishes an enticing interlocking configuration, which provides a shielded, yet ventilated, space for the chicken to be raised. The most innovative aspect of this chicken coop, according to Anderson, is the use of traditional Japanese techniques. Kuma draws inspiration from the yakisugi, or burned cedar: a traditional Japanese method of preserving the sliding surface of the timber. The burning process oxidizes the wood surface, creating a beautiful rusty texture and enhancing the panel’s functionality to resist firing, insects and weathering. These charred wooden panels cannot be more suitable for constructing a sanitary, weather-resistant home for the chickens.

The final architect focused on in the lecture is Shigeru Ban, a master in paper tube architecture. “Like Kuma’s, Ban’s work is also heavily rooted in modernism with references to tradition,” Anderson said. Ban’s most innovative works are his humanitarian shelters for the underprivileged people and victims of disasters across the globe, such as the Hualin Elementary School in China and Paper Log Houses in India. He employs disposable, inexpensive paper tubes and cardboard of decent quality to construct highly durable, functional buildings within a limited amount of time. One of his projects, the Paper Partition System II, is a honeycomb framework constructed in the shelter stadium to accommodate the homeless people after the 2005 Fukuoka earthquake. Evacuees suffered from a lack of privacy and high density in the crowded stadium. Inspired by the tatami concept and screen use, Kuma used simple cardboards to cover the floor for people to rest and create a partition to ensure nighttime privacy. The flexible structure of cardboards is a genius invention that maximizes the utility of the space and provides convenience for the dense population.

Ban extended his use of cardboard and paper in the construction of monumental architecture such as the Cardboard Cathedral in New Zealand and Paper Church in Japan. Though these buildings are only for temporary use, they are magnificent and environmentally friendly. One of the culminating projects with the use of Ban’s oeuvre, as Anderson introduced, is the Paper House for his private use in Yamanashi. This beautiful weekend villa is his first attempt at transferring the humble and fragile material, including the cardboard and paper tubes, into a permanent building. The S-shaped colonnade of the house consists of 110 paper tubes, recalling the graceful Japanese bamboo fence found in traditional buildings.

Anderson’s lecture on Japanese architecture was fascinating and thought-provoking. He took into consideration a diverse audience pool, who may or may not be familiar with Japanese arts and culture, and employed simple language to introduce new architectural terms and philosophical concepts of different masters. Rather than a general overview, Anderson led us to understand and appreciate the simplistic beauty, delicate details and natural harmony featured in Japanese architecture.

Please note All comments are eligible for publication in The Justice.