Vaune Trachtman: ‘There’s always a way when you’re an artist to find your way.’

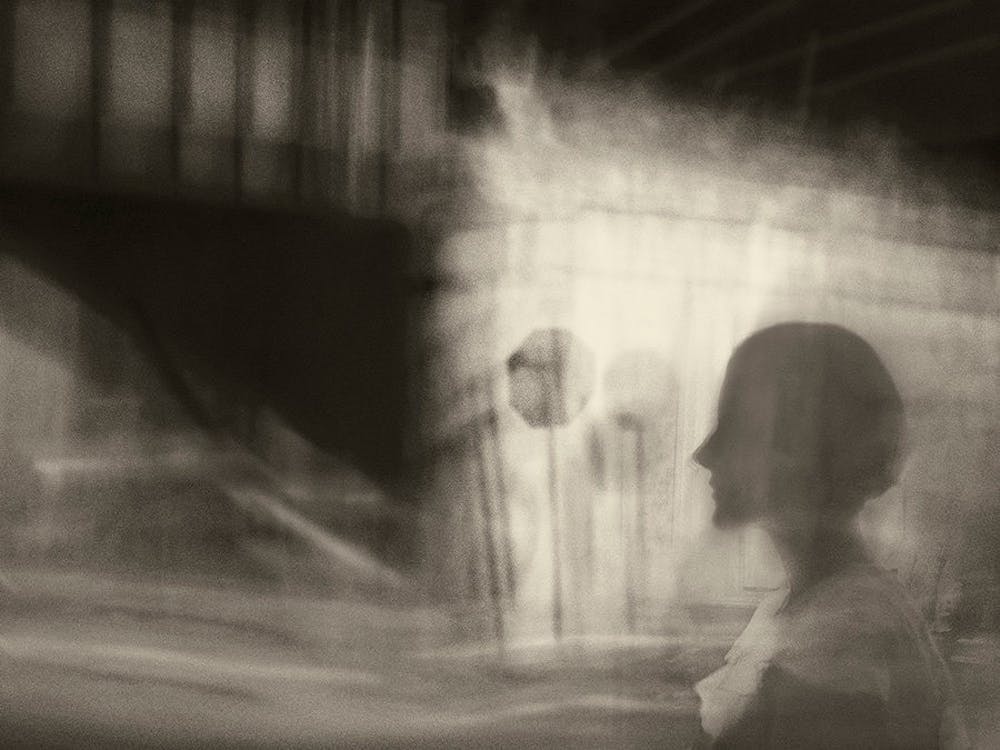

“NOW IS ALWAYS.” Is our past always present and the future already here? On my computer screen I can see the photographs of Vaune Trachtman — a collection of fleeting, evanescent memories. In spite of its immaterial quality, NOW IS ALWAYS is more about permanence rather than loss; remembrance rather than oblivion. Mixing her father’s negatives from the Great Depression with pictures taken on her iPhone, the master printmaker created a series of photopolymer gravures that expand the concept of family memorabilia. Invented in the late 19th century by the photography-pioneer William Henry Fox Talbot and Czech artist Karel Klíč, photogravure belongs to the Intaglio family of printmaking. It consists of capturing an image on a plate that is printed by pressure through an etching press. Deceptively simple in theory, it is a photomechanical process of tactile delicacy and painstaking craftsmanship. Trachtman’s prints were showcased in a solo exhibition at the Griffin Museum of Photography in Winchester, MA, from May 26 to July 9. “NOW IS ALWAYS” is a mystifying body of work that unbinds the constraints of time with exquisite texture and electrifying motion.

As a former student of the Tyler School of Art and Marlboro College, Trachtman received her M.A. from New York University and The International Center for Photography. After 15 years of working in the imaging department of TIME Magazine, Trachtman experienced the transition of photography from analog to digital. In “NOW IS ALWAYS,” this first-hand exposure allowed her to breach the gap between images captured almost a century apart. Honoring the methods and tones of historic processes, Trachtman sees traditional practices and new imaging technologies as organic extensions of each other. “The history of photography has influenced the way we capture images now digitally. It has to do with the way photography was first made, even back to the camera obscura. At the end of the day, photographic techniques build on each other. It’s all that same kind of technology.” Beyond the interconnected evolution of image-making, the printmaker believes that the key difference between traditional and digital mediums lies in the materiality of the art object and its relationship to the body. “There’s all this digital work that I love, but I really missed the physicality of making a print. With photopolymer gravures, you’re getting your hands inky and with those big prints… Oh boy! It’s so incredible and physical! You have to keep moving in order for everything to not smudge. You have to do everything very gingerly.”

Since the creation of the first successful photographs by Nicéphore Niépce in the early 19th century, imaging techniques have blossomed into a lavish bouquet of alternative photographic processes. Trachtman, who describes herself as a process-oriented person, has always gravitated toward a more intimate, bodily connection with image-making. “Working with other people’s pictures, I felt less hands-on. That’s when I was able to transfer to the imaging department at TIME Magazine and become a retoucher. That was more of that process-oriented thing that I wanted to get back — to getting as close to the thing that you are actually going to hold in your hands.”

Before becoming an established imaging specialist, Trachtman spent her nights on the dance floor at The Rebar nightclub experimenting with a tiny Minox camera that she found at a yard sale in Seattle. In a symbiotic dance, her camera became an extension of her body. Her eyes moved intuitively as it chased lights and shadows to the beat of the music. Her early image-making was a dance of blurred visions driven by the senses. The kineticism of these early slow-shutter images is a buzzing aesthetic that continues to permeate her photographic oeuvre. Many of the backgrounds included in “NOW IS ALWAYS” were taken from windows and moving vehicles. The artist, after losing her parents at an early age, was “pretty much on her own” and was “rarely in one place for very long,” and found her sense of belonging in a permanent moving state. “I love to always be moving. Even if I’m in a place very still, I need that 15th of a second as the sweet spot in my camera because it’s a slow shutter speed. Looking at all of my personal work, I try not to have anything in mind that it’s going to tie up to one time and place. I try to encapsulate time instead.”

In addition to the blurred bridges, highways and roads that decorate her industrial landscapes, the artist developed a kinship for a similar kind of energy.

“I love being in a public space,” says Trachtman from the solitude of her dimly lit studio. “I love that in a public space, everyone is welcome to come in. If you ever go to a square and it’s early in the morning, you can still feel, see and remember everyone that’s been there. I try to take pictures of that energy and motion. It’s a lot of what my work is about.”

In spite of having found her voice documenting the world around her, Trachtman remains aware of the solitary side of art-making. After getting lost in the come-and-go of public places, the artist retreats to the solitude of her darkroom. Alone with her printing press, she finds the time to have an intimate dialogue with her work. “To be in the studio, to be by myself…it gives me perspective. When you’re really into what you’re doing, you lose sense of time, right? All of a sudden, I’ll be in the studio and I’m like, ‘Why is it dark in here?! Oh right, the sun has gone away!’ I need both sides of the process.” Looking at her artistic production from a bird’s-eye view, Trachtman focuses her alone time on cultivating a style that is both experimental and consistent. “I feel very strongly about a series in which each image has a dialogue with the other one. I need time to see what the consistent voice is in all the work — see if everything holds together.”

Caught in-between the material and the unmanifested, some creative ideas never see the light of day. Luckily for Trachtman, the materialization process is where she naturally thrives. Tuning into her creative instincts, the artist believes “there’s always a way when you’re an artist to find your way.” Trachtman’s solo exhibition at the Griffin Museum was the culmination of a year-long production process. It started with a creation grant through the Vermont Studio Center and was completed through a creative residency at the Tusen Takk Foundation in Leland, Michigan. As she reminisces about the creation stages of “NOW IS ALWAYS” and the institutions that supported her work, she recalls navigating the initial uncertainty of creating a new series during the COVID-19 pandemic. “I didn’t quite know what I was going to do. I felt like my last series was done and I was ready to venture out.”

It was around late February 2020 when Trachtman acquired a year-long residency at the Vermont Studio Center and “NOW IS ALWAYS” officially took off. “I had a picture titled ‘Tenement Roof’ that I wanted in my last series, ‘ROAMING.’ But, it was the only one that had people in it, so it didn’t work. I really wanted that in some series so that became a key image for ‘NOW IS ALWAYS.’” Serendipitously, Trachtman’s sister had recently found a collection of 91 negatives her father had taken during his time as a journalist for the Philadelphia Inquirer. What started as a readily-available source for image-making became a timely opportunity for the artist to learn more about the history and people of Philadelphia, her father’s past and her own. Considering the documentarian aspect that she and her father’s work share, Trachtman believes “NOW IS ALWAYS” became part of a larger historical narrative. “My father lived through the last pandemic in 1918 and the pictures were taken during the Great Depression,” she said. Her work is “a dialogue and homage to the history of photography,” she added. “I also get to span that whole time frame with what I’m doing with my process. I go from digital and all the way back to photogravure, which dates to Henry Fox Talbot and the first photographs. It’s really bringing history alive for me.”

With a vault of negatives to develop, Trachtman applied to a creative residency at the Tusen Takk Foundation, a place that was essential to the culmination of her series. “The Foundation was such a perfect place for me. In order to do what I do, I need big Epson printers, an exposing unit, a press and trays and sinks big enough to develop my plates. I need a dark room and surface area. Not only did it have all these things but it had it at a scale that was larger than I’m able to in my studio.”

Alongside the possibility of creating personal work at an unprecedented scale, new opportunities for artistic exploration emerged. Formerly a master printer of silver gelatin prints and asphaltum-based photogravures, Trachtman became weary of the hazardous chemicals. “I had to go green. The old-school gravure process is really toxic. I didn’t want to be working with that kind of chemistry. After working in a dark room for so long, I am very sensitive to certain things now.” Based in Brattleboro, Vermont, she now specializes in non-toxic processes. “NOW IS ALWAYS” was made with a direct-to-plate photopolymer gravure method, a relatively recent, non-toxic alternative to the original photopolymer technique. Trachtman’s transition to studio-safe materials stemmed not only from health concerns but also her increasing environmental awareness that challenged her to modify her practice. “It’s paramount for me. It’s satisfying to make an image and feel like I don’t have a bad conscience. When I used to work in the dark room, you were supposed to use gloves and tongs because of the chemicals. I’m very impatient, so it’s really nice to be working with something that’s more environmentally friendly.” Planning into the future, Trachtman is looking forward to exploring the possibilities of more alternative processes: “There are ways to do photography using instant coffee or vitamin C. At some point, it would be exciting to try to experiment with other non-toxic methods.”

Although her printing techniques may or may not change along the way, the photographer feels that “NOW IS ALWAYS” became part of a larger project that has yet to fully materialize. “I just found these pictures that my dad took in the 50s and 60s that I didn’t realize I had. The negatives that my sister gave me were around 91 single frame images. And of those, there’s only so many that are people.” In spite of having limited remnants to source from, working with historical sources allowed Trachtman to redimension the personal impact the series was having on her. “I didn’t know my dad. This is a way for me to feel connected to him and to learn more about him. In the beginning, I didn’t realize what I was doing. I just had that key-picture and I needed people. My father’s negatives just happened to be around. I didn’t realize the obvious aspect, that this could be emotional… It was very subconscious.”

As “NOW IS ALWAYS” morphed into a personal exploration of memory and family legacy, Trachtman developed a special connection with this particular series and, at the moment, with one particular picture. “With other series I have favorites. But with this one, I have six or seven of them! Right now my favorite is ‘Bound,’ the one with the person in the air. Are they falling? Are they rising? Whatever they are, they’re above and I feel like they have perspective. I feel like I need a little bit of perspective right now.” As she keeps looking for ways to keep the art-making machine running during quarantine, the artist is currently determined to keep the momentum of “NOW IS ALWAYS” going. “I got to a certain point of the pandemic in which I found a new kind of voice to keep moving forward with this series. I don’t think it needs to be exactly the same but I just feel like there’s more to say with this series that I haven’t said yet.”

Although the Vermont sun has set, Trachtman has a long workday ahead of her. “I have a studio visit later today and there’s some negatives I need to develop,” she says jokingly referring back to her environmental practice. “I’m sure direct-to-plate also has at least some level of toxicity. It’s supposed to be less toxic, but, you know, some flowers are toxic. Everything has something. (Laughs) It’s hard not to be a hypocrite!” As she puts her father’s negatives away, she is abruptly overtaken by contagious joy and passion. “It’s a really wonderful thing that I have found all this new source material that I can work with, you know? It’s been a wonderful experience to do this.”

“NOW IS ALWAYS” was the inaugural exhibition at the grand reopening of the recently renovated Vermont Center for Photography in Brattleboro and will be showcased Sept. 3 to Oct. 31, 2021. Vaune Trachtman’s work has been supported by the National Endowment for the Arts and the Vermont Arts Council, and it has received additional support from the Tusen Takk Foundation.

Please note All comments are eligible for publication in The Justice.