Experts discuss history and implications of Ukraine crisis

The panel covered Ukraine’s role in geopolitics, oil relations, and a potential no-fly zone.

Prof. Sabine von Mering (GECS) exclaimed that when the Center for German and European Studies first began planning the “Contextualizing the Ukraine Crisis” webinar set to take place on March 22, they were not expecting the countries to be at war. Following Russia’s Feb. 24 invasion of Ukraine, however, von Mering continued “we now find ourselves in the fourth week of war, with thousands dead, millions fleeing, and numerous hard economic losses.” In order to fully understand this crisis, it is important to look at it from a political and economic context and evaluate Germany’s crucial role in all of this.

The event featured three speakers — Prof. Steven Wilson (POL), Simon Pirani (University of Durham) and Marcel Roethig (Friedrich Ebert Foundation, Kyiv, Ukraine) — who dissected “the broader context of the Ukraine Crisis,” per the event description.

Ukraine serves as a “West-East junction point,” Wilson explained. It is a critical place that “straddles” the boundary between Europe and Asia, which invites the dichotomy of the East versus the West and who should have control over this territory. More recently, Ukraine has been subject to a lot of Western and Russian imperial aggression. However, the territory has remained relatively split on ethnic and linguistic maps as well as politics, Wilson said.

This, Wilson said, is often used as an excuse for Russian acts of imperialism, especially in the context of the current invasion “where there is this notion of Russia as defender of the Slavs [who protects] the ethnic Russians who are being abused by foreign powers.” President of Russia Vladimir Putin certainly subscribes to this line of logic, Wilson explained.

“I think it’s critical to understand that Putin’s perspective here isn’t irrational; you might not agree with it, it might be evil, but it’s not irrational. It’s not the actions of a madman,” Wilson continued. Throughout his presidency, Putin has strongly advocated for the resurgence of Russia as a major power, so this ideology is not “out of the blue. It is a combination of 20 years of foreign policy,” Wilson said.

Thinking about how the conflict can end is where things get dicey and the situation gets “scary.” Putin is “insisting that it is existential for Russia to control its buffer states” and is acting in service of the long-term legacy he hopes to create, Wilson said. This means there aren’t any “off ramp” or otherwise diplomatic options. The options for Putin are winning or losing, neither of which are good in terms of minimizing casualties or ending human suffering.

Another key component to understanding the Ukrainian crisis is understanding the underlying economic influences. These motivations do impact Russia’s actions, but “Putinism,” as termed by Pirani, has “shown a great skill for compensating for Russia’s economic weakness with military strength.” Pirani explained how the gas trade is crucial to Russia-Europe and Germany relations, but the “last 30 years have been a story of decline of that relationship,” Pirani said.

Russian gas revenue is achieved either through imports to Ukraine or to other European countries, which travel through pipelines in Ukraine. As tensions have grown between Russia and Ukraine politically, the gas imports from Russia to Ukraine have reduced, Pirani continued. There were low levels during the Crimean crisis in 2014 which resulted in the overthrow of former president of Ukraine Viktor Yanukovych, and imports stopped completely in 2016.

However, Russia still transports gas through pipelines passing through Ukraine. In trying to find a way to transport gas from Russia to Germany without passing through Ukraine, the Nord Stream 2 pipeline was proposed. “Had it been completed, it would not have increased the amount of Russian gas that Europe would have used,” Pirani explained. “It would have [transported] gas [to] Europe [via passageway of] the Baltic sea.”

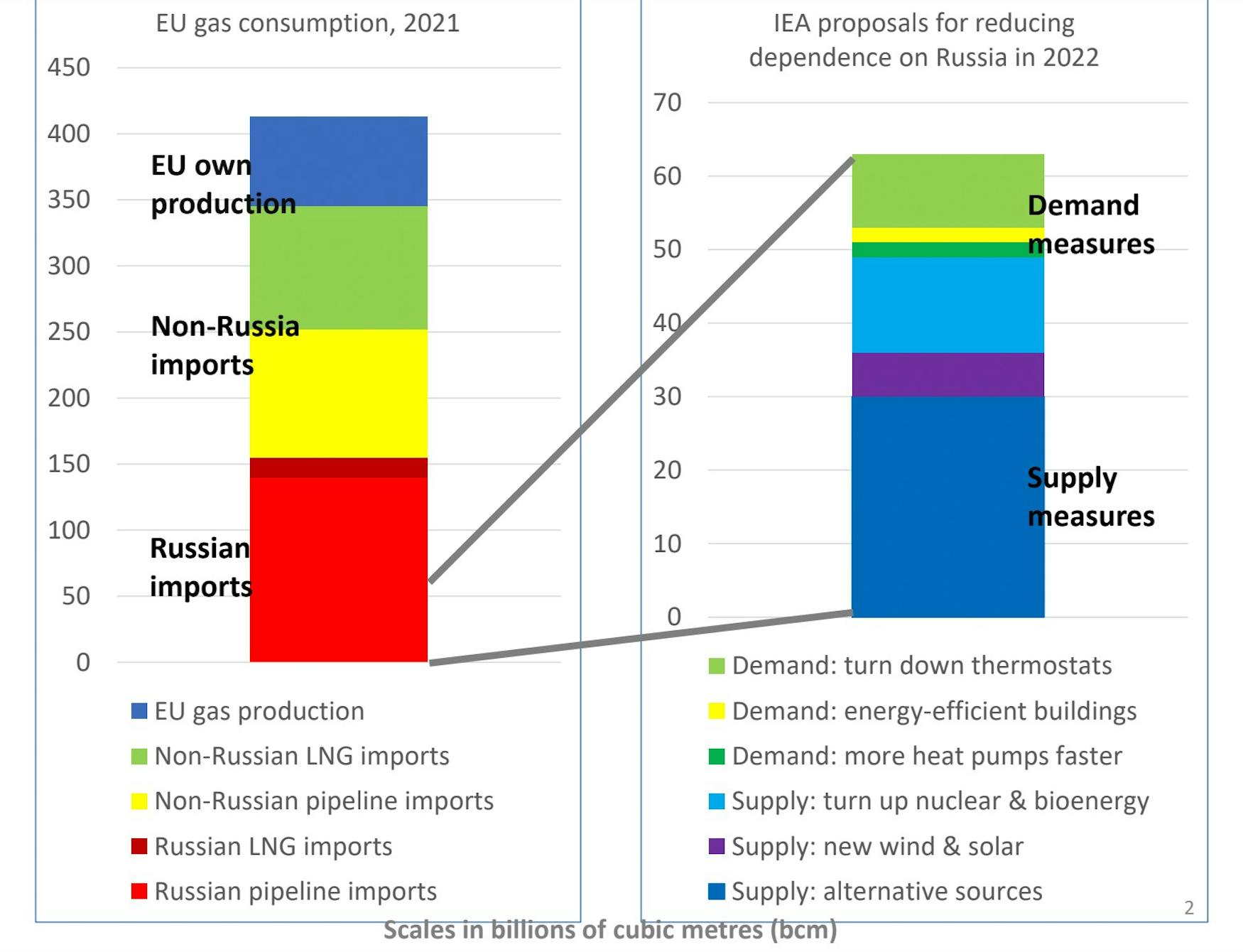

From here, there are two routes to take, Pirani continued. Countries can either get their energy somewhere else — in the form of renewable energy, etc. — or they can take actions to lower the demand rates for energy. These demand measures are very good for climate policy. Beyond just that, though, it is important to think about how countries are spending money on energy. This, von Mering said, is a form of income worth “billions of dollars a day” that is kept out of sanctions and is therefore helping to fund Putin’s war.

Roethig joined the conversation from Germany as he had fled Ukraine and was no longer at his Kyiv office. Most of his 20-some colleagues, Roethig explained, are still trapped in Ukraine under fire, in shelters, as refugees, and/or without water.

Roethig explained that when the Minsk Agreement was created in September 2014, it marked an end to the war in the Donbas region of Ukraine. Germany, Roethig said, saw itself as a “mediator” in this agreement. The Germans, he continued, wanted to help Ukraine modernize its economy and supported Ukraine in everything except for arms deliveries. After the end of the Cold War, “we believed our armed forces were really only there for peacekeeping issues,” Roethig said. “We saw our mission in international peacekeeping rather than defending our land.” This poses a large problem now as Ukrainian forces were not prepared militarily for a large-scale invasion and have struggled to defend themselves. Germany is now delivering arms to Ukraine, but some people question if this is enough.

Finally, the speakers turned to the issue of a no-fly zone. Although a no-fly zone would be cause for a potential World War III, some have advocated for this option, von Mering said. She then turned the question to Roethig. He explained that his colleagues sometimes ask why a no-fly zone has not been implemented. Roethig attributes this desire for a no-fly zone to their stressful situation since a no-fly zone would not be the most rational decision. Practically speaking, although Roethig did explain that the practical point of view can sometimes have little meaning when you are in the middle of a large-scale conflict, a no-fly zone would not help much because there have been fewer planes and more missiles recently, per Roethig. Instead he advocates for anti-aircraft systems, which are currently being delivered. This war, he explained, is far from simple. Although a no-fly zone “could end this war in several hours, none of us would be there tomorrow to speak about it.”

Please note All comments are eligible for publication in The Justice.