‘We failed as a nation and were betrayed’: Former Afghan diplomat, alum speaks out a year after Afghanistan’s fall

The Justice spoke with former Afghan diplomat Naveed Noormal M.A. ’16 to learn more about Afghanistan and its complicated modern history.

The United States launched its “War on Terror” in 2001, when a U.S.-led military coalition invaded Afghanistan in response to the 9/11 attacks carried out by the global terrorist group al-Qaeda, who were being sheltered in Afghanistan.

On Sept. 20, 2001, former President George W. Bush announced the War on Terror, saying, “Our war on terror begins with al-Qaeda, but it does not end there.” Just over two weeks later, coalition forces began an air campaign against al-Qaeda and Taliban targets. The Taliban — a fundamentalist political movement that harbored al-Qaeda — controlled Afghanistan at the time of the U.S. invasion.

The U.S. and its allies overthrew the Taliban government in December 2001. Less than a year into the war, the Bush Administration began focusing its efforts on setting up a new governing body in Afghanistan. “Peace will be achieved by helping Afghanistan develop its own stable government,” Bush said in an April 2002 speech. The U.S. supported the creation of the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan. Although it was designed as a democratic government, the new system was riddled with corruption.

In August 2021, two weeks before the U.S. withdrew all troops from Afghanistan, the Taliban recaptured the country’s major cities, deposing the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan. The Taliban took control of Kabul, the capital of Afghanistan, on Aug. 15. On Aug. 30, the last U.S. troops left Afghanistan.

Lasting two decades, the war in Afghanistan is the longest in American history. Nearly 2,500 American service members died fighting in Afghanistan. At least 46,000 Afghan civilians have been killed in the war, according to a 2022 report from Brown University, while 3.5 million had been displaced by the end of 2021, according to the United Nations. This number does not take into account “indirect consequences” of the fighting, such as disease and loss of access to food and water. Today, Afghanistan is fully ruled by the Taliban.

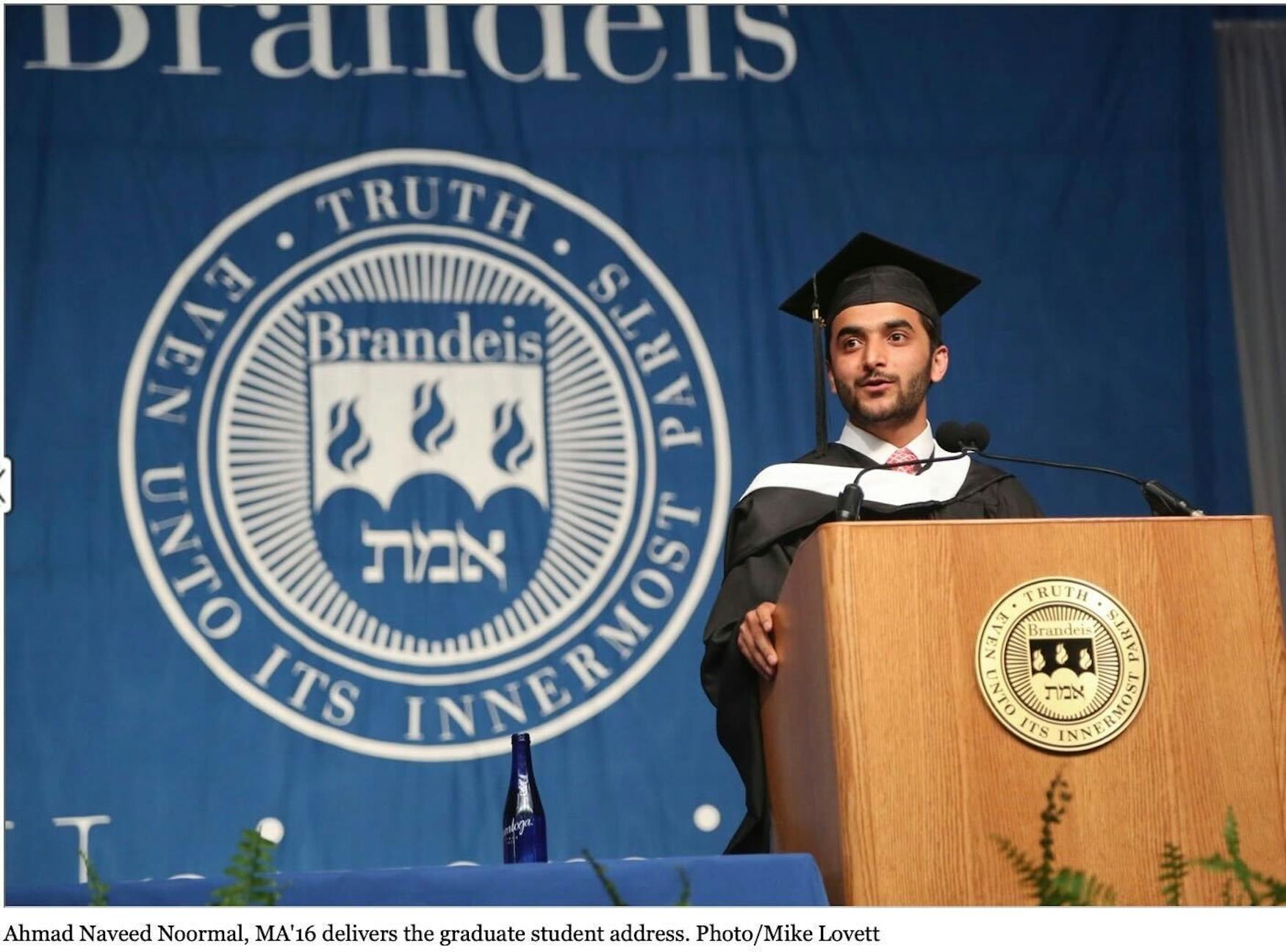

Naveed Noormal grew up in Afghanistan. For over 10 years, he devoted his career to supporting his home country through diplomacy. He now lives in London and works as a journalist for Volant Media, Afghanistan International. Noormal, a Fulbright Scholar, received his Master’s in Conflict Resolution and Coexistence from the Heller School for Social Policy and Management in 2016. He was originally drawn to the University after hearing a talk by Prof. Alain Lempereur (Heller) while Lempereur was visiting Kabul.

After graduating from the Heller School, Noormal served in the Afghan Deputy Foreign Minister’s office. In late 2017, he was assigned to the Afghan Embassy in London. He first led the consular services section of the Embassy, providing services to Afghans in the United Kingdom and U.K. citizens interested in Afghanistan. He then took on the political engagement, economic cooperation, and strategic communications portfolios, wrapping up his time there in January 2021.

Noormal spoke to the Justice via Zoom March 8, answered follow-up questions via email in August, and provided further updates in September also via email. He spoke about his path to the University, his work in the Afghan Foreign Ministry, and his thoughts on America withdrawing and the Taliban taking over his home country just over one year ago.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity. The views expressed here are solely those of the interviewee.

The Justice: What did you make of your experience at Brandeis?

Naveed Noormal: When friends ask me this question, I answer that if I could live only two years of my academic life, it would be my two at Brandeis. The two years I spent at the Heller School are very close to my heart. It was all I wanted in a school.

TJ: You were serving in the Afghan Embassy in London as the Trump administration negotiated the Doha Agreement with the Taliban. Signed in February 2020 by the Trump Administration, it promised a complete U.S. withdrawal from Afghanistan by May 2021 — later extended to Sept. 11 by President Joe Biden — in exchange for the Taliban not attacking U.S. troops. What did this process look like from your vantage point?

NN: The Doha Process began the weakening of the Afghan Republic. On one hand, the process was leveraged by the Taliban by excluding the relatively stable government in Afghanistan, and on the other, the government of Afghanistan miscalculated the U.S. support [as] inevitable. The dominant understanding among the government officials was that our allies in the U.S. would not leave us unless a settlement was reached.

TJ: What were you seeing and thinking during the final few months before Afghanistan fell to the Taliban?

NN: I remember in late July 2021, I met former colleagues at the Embassy. We were discussing the situation in Afghanistan, and we were extremely worried about the fall of provinces, one after the other. Despite the quick fall of the provinces, we thought that if Kabul and a few other provinces would not collapse, the negotiations would enter a difficult stage.

I asked a colleague at the embassy whose mission was ending, “Are you planning to go back to Kabul at this point or stay in the U.K.?” He told me that if Kabul stays with the government, he’ll go back, but if Kabul falls, then it would no longer be safe. “I don’t think Kabul would ever collapse,” I answered with a smile. I thought that the Taliban were balancing their power at the negotiation table with their progress in the battlefield and would finally sit and talk about how to share power.

A day after our conversation, we learned that the two important provinces of Herat and Nangarhar fell to the Taliban. At this stage, I realized that we were wrong, and the collapse was inevitable. Finally, on Aug. 15, we learned that Kabul collapsed, and the Taliban entered our capital city. My nation felt betrayed and shattered.

TJ: What did you make of President Ashraf Ghani and his close aides fleeing to Abu Dubai in the final days as the Republic fell? (Ghani was the second and final president of the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan.)

NN: It was painful to hear, especially for people like me who had invested ourselves to public service. We worked tirelessly for these hard-earned values in the past 20 years. The day we heard that the president had left, we felt betrayed, hurt, and that we failed; I am afraid we failed as a nation and were betrayed by our leaders and international partners. This was not only a betrayal of the people of Afghanistan, but also of the sacrifices in blood and treasure of American and allied soldiers and taxpayers. A lot of souls were sacrificed to gain and preserve these democratic values, and they were vainly compromised.

TJ: In terms of a political settlement with the Taliban, what did you think it would look like post-Doha?

NN: Before the collapse, there was a consensus in the government at the regional and international level that there was no military solution, and there would be negotiations to reach a political settlement. However, it was important to reckon with the cost of the settlement. Our understanding was that the Afghan government and the Taliban would come to an agreement over the type of government, elections, constitution, and other essentials; as a result, a power-sharing government would be very likely.

TJ: In reality, what happened in those final months from your perspective?

NN: In April 2021, President Biden made it clear that the U.S. wanted out by September 11, 2021. But even then, when they were talking about the withdrawal agreement, we thought that the U.S. would continue to support the Afghan government, at least until a settlement was reached. But that was not the case. U.S. forces withdrew from Bagram Air Field, the largest American base in Afghanistan, overnight and didn’t even bother to let the Afghan government know about it. This decision immensely affected the morale of our soldiers in the battlefield at that time.

I agree that a lot of responsibility goes on the shoulders of the Afghan politicians, who could not create a political consensus in a time of crisis in Afghanistan. However, the international community and our strategic partners share equal responsibility for not listening to the will of the Afghan people. We, the Afghans, lost a huge opportunity to work for the better future of our country, and together with our partners, we lost a bigger opportunity to avoid the potential risk of regional instability that could threaten global security in the long run.

TJ: Do you think you have a role in the future of Afghanistan?

NN: I would love to and hope to return to Afghanistan. However, to be able to serve Afghanistan once again from within the government, it must be a government that respects democratic values, international human rights, and recognition by the people of Afghanistan and the international community. This will happen, and I believe and have hopes that my future belongs to Afghanistan.

For the future to look better, international engagement is paramount to pressure the Taliban to come to an agreement with all the parties involved in Afghanistan and establish a government that reflects the will of all the people of Afghanistan.

Please note All comments are eligible for publication in The Justice.