The last chapter: A review on ‘John Wick: Chapter 4’

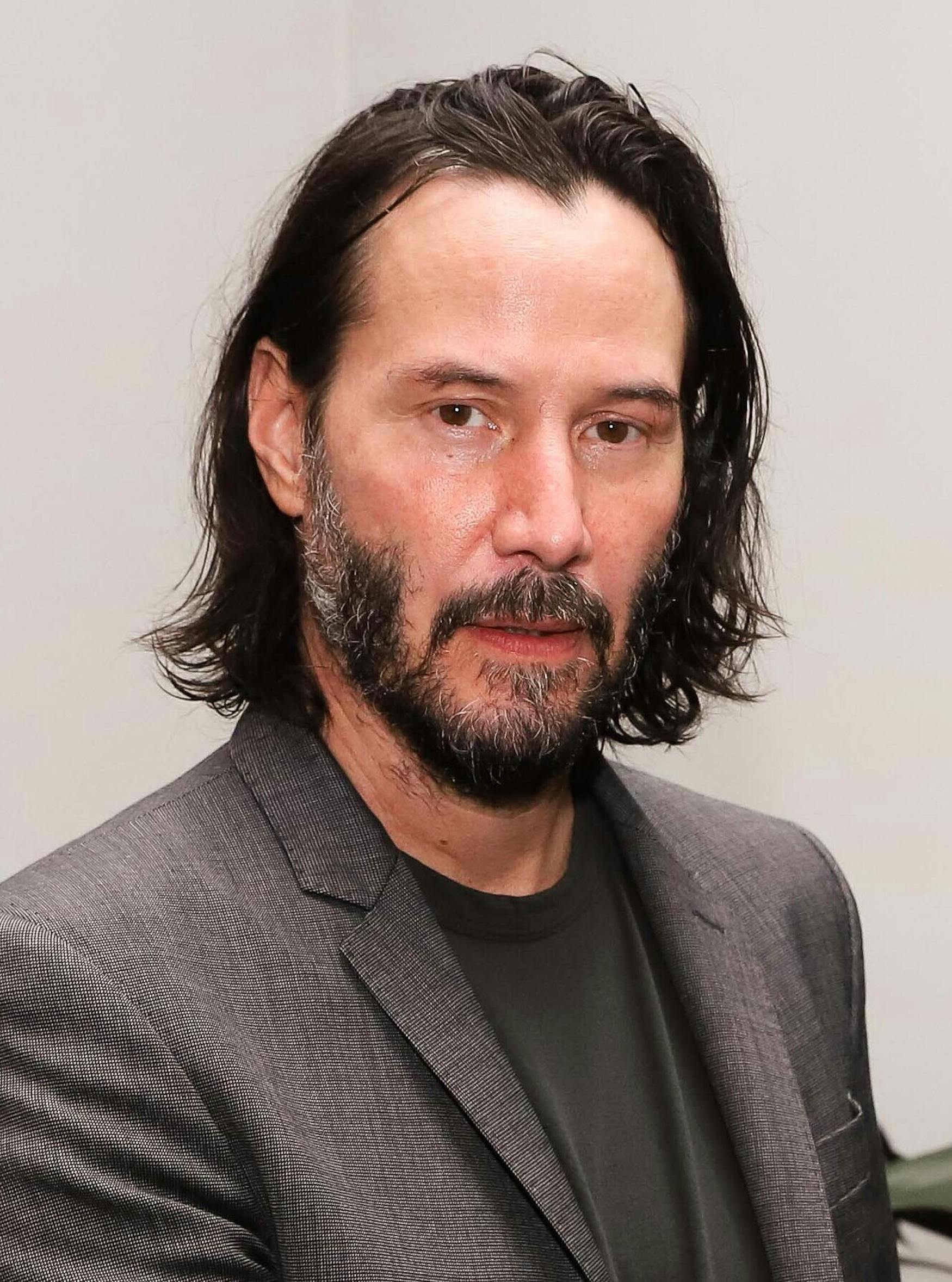

“Yeah, I’m thinking I’m back.” After a long four year hiatus, precipitated by the pandemic and other conflicts, John Wick (Keanu Reeves) has returned. And with his return arrives the greatest action film of the last 10 years. Directed by Chad Stahelski, Keanu Reeves’ former stuntman on “The Matrix,” “John Wick: Chapter 4” is the latest entry into this original action thriller franchise that has thus far dominated both critically and popularly. I have been looking forward to this film since the third one ended four years ago. So when I entered the theater on March 23, I had nothing but high expectations. It did not disappoint.

In this film, John Wick finds himself forced to fight the High Table, the mysterious organization of assassins that governs the hyper-realistic world of John Wick. His allies are the former manager of the New York Continental Winston, the Bowery King, and the friends he has made in his decades involved in the assassin trade. His travels take him to Osaka, Berlin, and ultimately Paris, where he seeks to destroy the Marquis, the man hired by the Table to dispatch John. At the end of the day, the John Wick franchise is a masterclass in stunt work and action set pieces. From the Red Circle nightclub fight in “John Wick 1,” where the kills are synchronized to the music, to the infamous dog scene in “John Wick 3,” the John Wick films has given us more high art action than any modern franchise. Somehow “John Wick 4” outdoes its predecessors. Essentially, the film can be broken down into five extended action sequences. The first is the absolutely stunning Osaka Continental scene. The way the incomparable Hong Kong action legend Donnie Yen directed the action throughout the sequence sets a new bar for how action should be done in Hollywood. Although his character is blind, he manages to not only compete with Wick but consistently surpass him. Their hand-to-hand duel is a balletic entrancing dance of brutal violence.

We then move to Berlin, where John must find the Ruska Roma, his crime family. There, they task him with killing Berlin Continental manager Killa, played by martial arts cinematic mainstay Scott Adkins, in revenge for the death of Pyotr, John’s mentor in the Slavic underworld. Of course, this new enemy is in a modern nightclub, incidentally surrounded by a system of waterfalls. Here, Stahelski gives us the best individual action moment since “Mad Max: Fury Road.” Killa and Wick fight surrounded by waterfalls amid the raving crowds of intentionally oblivious dancers, all to the sound of pounding techno music. This carefully choreographed exercise of martial arts precision and unambiguous brutality is something to behold. Fighting on various levels, they find themselves echoing many classic duels in pop culture. In Adkins’ performance, we see echoes of a Kingpin like character from the Daredevil/Spiderman universe, especially in how Killa uses his gravity and immense size to essentially bat John around. The combat we witness in this sequence is unlike anything that has been done in the franchise, much less Hollywood. Attention to detail is something that Stahelski never seems to abandon. Despite the distractions of the dancers, waterfalls and the seemingly unending wave of soon to be dispatched henchmen, we never lose sight of the main players and the way they weave together art and violence.

The last hour of “John Wick Chapter 4” is the greatest continuous hour of any action movie that has ever existed. There is more action in this hour than in most movies. In this clearly third act, John is given one task: to get to the top of Sacre-Coeur before sunrise. The Marquis sends everything it can to prevent him. The first scene alone would be a sufficient conclusion to this film. Stahelski has him fighting in the center of the Arc de Triomphe roundabout, and the results are expectedly off-the-wall insane. While people are flung into moving cars, John moves in and around traffic like a real life Frogger game, and this is all being done with as few cuts as possible. The amount of work that a sequence like this must have required is astronomical. Although the cars are sped up digitally, stuntmen are really being hit at 30 miles per hour, and even at that lessened speed, things can go wrong.

As if following a scene like that is even possible, “Chapter 4” continues to elevate itself with its next action sequence. Having escaped from the onslaught of vehicles and armored cars, John enters an abandoned apartment complex, where he quickly finds himself having to kill 30+ men armed with guns that are essentially mini flamethrower shotguns. Any other action director would deliver this scene with a bunch of quick cuts and hard to see gunfire, but Stahelski is unique. Instead, halfway through the sequence, the camera begins to pan up and eventually give us an eagle eye perspective above the various rooms. We see John almost blissfully putting an end to these disposable red shirts from a Hotline Miami-like perspective. At this point, my theater neighbors were smiling. Personally, I knew “Chapter 4” was going to be good, just not this good.

But the stuntman-turned director is not done. We still have the greatest achievement of the film on the horizon, the Sacre Coeur stairs scene. There are 237 steps leading up to the church, and John has to fight his way up them. Many critics have commended the franchise on its action, style, and clear focus, but I think there is something missing as to why these movies are successful. They use the environment perhaps more creatively than pretty much any film in its genre. The stairs sequence illustrates that. Stahelski and his team choreograph these scenes in a manner that forces the audience to keep the environment in focus. Everyone is tumbling down this intimidatingly steep hill, with the absence of cuts reminding us that these dangerous falls are being done by actual stuntmen. Amid this tapestry of controlled chaos, a consistently building tension remains in the background. Time is ticking, and we need John to get up this climb. Only films made by stuntmen for stuntmen can replicate this level of action filmmaking. There is an obvious intentionality behind the choreography that simply does not exist in the genre. While this is likely the last John Wick, spinoffs aside, I am grateful that I was able to experience seeing all four entries theatrically. They elevated action filmmaking, and we should all recognize their achievement for what it is. As for this one, my only advice is this: See it in a crowded theater while you can. It's worth it.

Please note All comments are eligible for publication in The Justice.