“Dirt Shrine” brings martyrs down to Earth

On April 26, Astrid Schneider ’23 and Juliette Lillywhite ’23 will culminate their honors studio art theses in a joint gallery opening, placing their distinct works in conversation to highlight themes of community and humility.

Neither Astrid Schneider '23 nor Juliette Lillywhite '23 entered Brandeis as Studio Art majors — both found the program by means of pure exploration. “During my freshman year I took 'Drawing Under the Influence'. It was the only class I cared about,” said Schneider during an April 20 interview with the Justice in the Epstein art studios, as they prepared their work for their and Lillywhite’s upcoming exhibit “Dirt Shrine.”

Rather than just taking the yearlong Senior Studio course required of all Studio Art majors, Lillywhite and Schneider both chose to simultaneously do a thesis, which requires students to create a thematically cohesive body of work, complete with curatorial statements.

The two saw the thesis program as one last push, both for their artistic sensibilities and their resumes, before applying for graduate art degree programs later in their careers. The thesis route also gives them access to more grants used to buy materials, which are sorely needed in the exceedingly small art program, whose budget spends a mere $75 on materials per student per semester for Senior Studio.

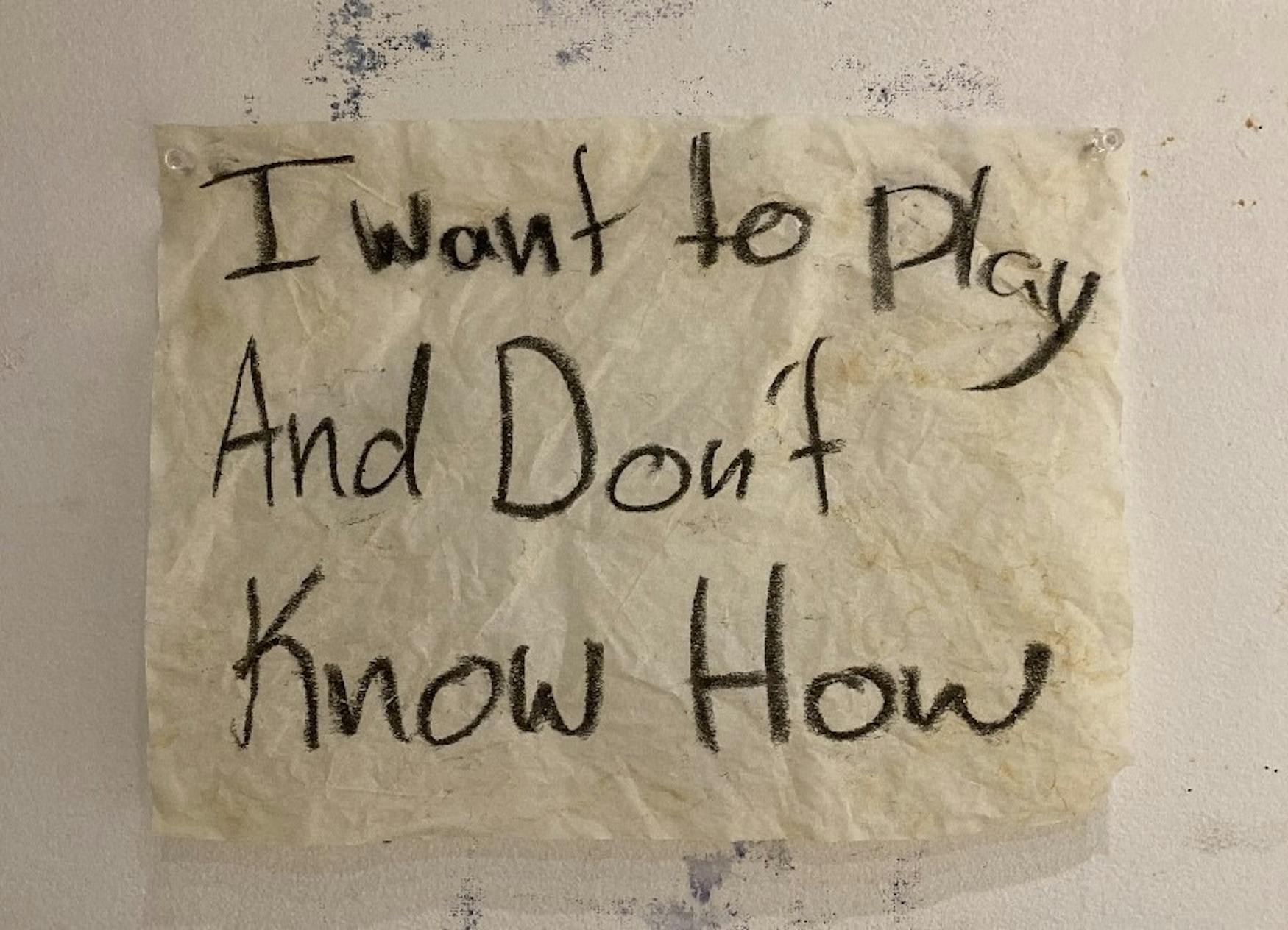

As for their projects, Lillywhite contributes the “dirt” portion of “Dirt Shrine,” working to redefine her notions of play as a former urbanite child growing up in New York City. “A child who grew up in a forest has a completely different experience of playing than someone who grew up in a city. I can’t experience these things as a child would, but I'm trying to let myself have that,” she said. Her workspace in the Epstein Building where all Senior Studio students store their work does indeed look like a forest, with live plants, tall beige tarps splattered with footprints, and, yes, dirt. Different materials and fabrics adorn the space like different plant species populating a grove. For Lillywhite, the pieces are invitations to herself to let go of ties to obsolete rigidity and embrace nature. She described one terrestrial experience that inspired her: “I saw a waterfall and it just changed everything. This thing is so powerful and I am nothing compared to it — we are all nothing compared to it — and I am so humbled.”

DIRT: Lillywhite, pictured, spearheaded the "dirt" aspect of "Dirt Shrine."

This humility draws a thematic line to Schneider’s workspace about ten paces away, the “shrine” element, filled with tall stacks of drawings and walled with printouts of religious writings and imagery. Their thesis concerns martyrdom — a concept they deem harmful.

“Religion has upheld this idea of the individual carrying the weight of the community, but that just isolates the individual,” said Schneider. Instead, they place value in socio-cultural practices that prioritize the collective. This means recontextualizing Abrahamic stories through illustration and sculpture — the most noticeable of which is an approximately six-foot-tall wooden Saint Andrew’s cross, a common feature of BDSM dungeons. Schneider’s exploration of sexual boundaries as they intersect with religious martyrdom manifests in this interactive piece, where the audience member can literally place themself on the cross using the restraints attached to it and then remove themself. “It’s demartyrization; taking yourself off this high place of suffering to lean on your community.”

For the gallery, it was very important to Schneider and Lillywhite that the two theses be in dialogue with one another, rather than simply sharing a space. Fortunately, they easily found a throughline in the abject humility of their projects. “Both of us are talking about things way larger than ourselves,” Lilywhite said. “Nature is religion. There is nothing stronger than the force that keeps the waterfall going,” with Schneider adding, “You look at that waterfall and you lose a self-identity, as it’s larger than any concept of yourself.” Both see the self as only valuable in conjunction with a sense of something larger, be it a secular community or a rotating planet. “It’s not about erasing yourself,” Schneider said. “It’s about finding a balance.”

With the opening date quickly approaching, the two are working quite literally around the clock — they were interviewed at midnight, still awake and laboring over their pieces. “In my mind, this is the beginning of my career,” Lillywhite said. Schneider echoed, “It’s definitely the culmination of everything we’ve done at Brandeis.” The pressure is mounting, but as two of only three students creating Studio Art theses, Schneider and Lillywhite have had access to integral guidance from their instructors. Prof. Sheida Soleimani (FA), told the Justice, “[Schneider and Lillywhite] have both been so thoughtful and articulate in considering their own practices, as well as the overlaps and intersections of their processes. It’s been a pleasure getting to know them both as well as seeing their work evolve.”

"It's not an option -- it doesn't feel like there's an alternative," Schneider said of their motivation to create art.

“We sat together for almost four hours just trying to think of the title — we want it to be fun, not pretentious,” Lilywhite said. Schneider added, “The goal is to have more of an install than a gallery — we want it to be a real shrine to the earth.”

Both artists feel an intense pull to create, exhibiting those creations is purely secondary. When it comes to making art, Schneider said, “It's not an option — it doesn't feel like there's an alternative.”

See “Dirt Shrine” on April 26 starting at 6:30 p.m. in the Kniznick Gallery in the Women’s Studies Research Center, with refreshments provided.

Please note All comments are eligible for publication in The Justice.