October in Brandeis history

Following a Saturday Justice reunion involving graduates from as far back as the 1960s — and inspired by an old practice of “This Week In Brandeis History” — we decided to dig through our archives for standout October stories.

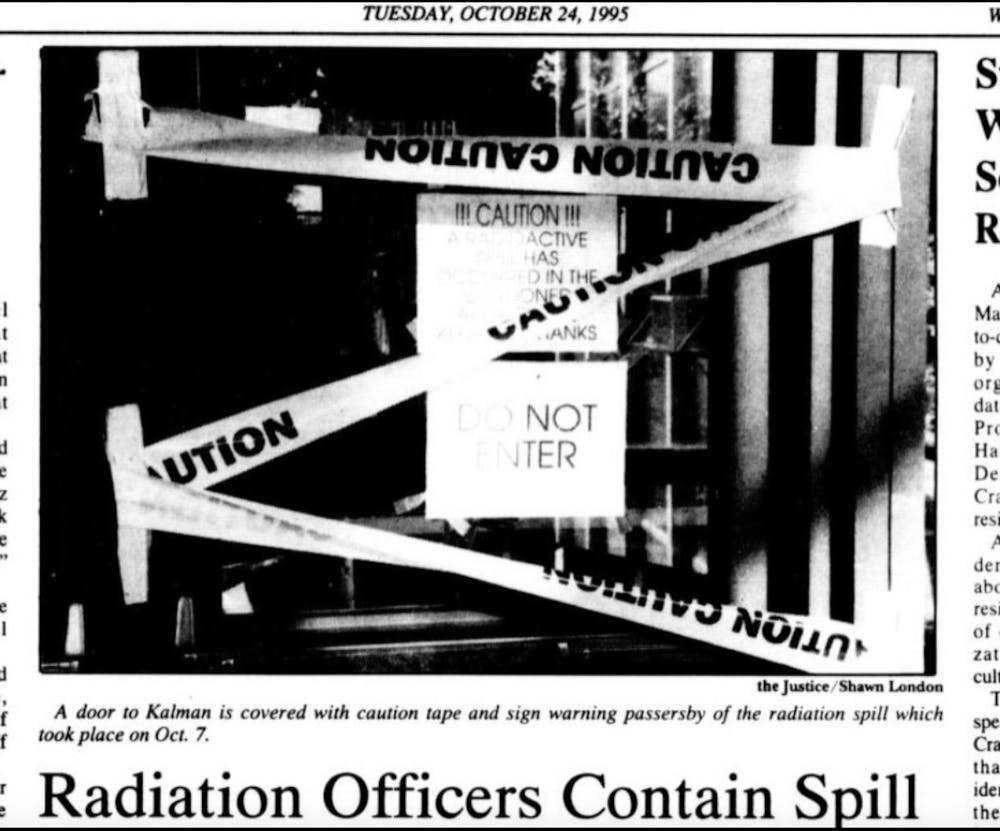

Oct. 7, 1995: Radioactive hazard contained in biology lab

On Oct. 7, 1995, a researcher spilled Phosphorus-32 — a radioactive isotope with a 14.3 day half life — in a lab in Kalman Science Center. According to an Oct. 15 Justice article, it took two hours for the spill to be caught, at which point the researcher had tracked the phosphorus from their shoes into other parts of the building. While the quantity spilled wasn’t particularly dangerous, according to radiation safety officer Robin Bell, “some surfaces” where P-32 was tracked in Kalman were “porous” and therefore there were concerns about removal. Simultaneously, a multitude of people stepped in the spill prior to the containment by Bell and his team, causing worries about poisoning.

“Quite a few people have come to me with concerns, but none of the students who have come forward tested positive [for radioactivity],” said Bell, who used a Geiger counter to scan for contamination. He said that the rubber soles of shoes are actually good barriers to P-32. “We don’t expect any problems.”

The outside of the building was covered in “non-stick, weather-proof resin” in order to contain the spill. The covering was set to remain for four to five months, according to Bell, which would give the substance enough time to break down away from students.

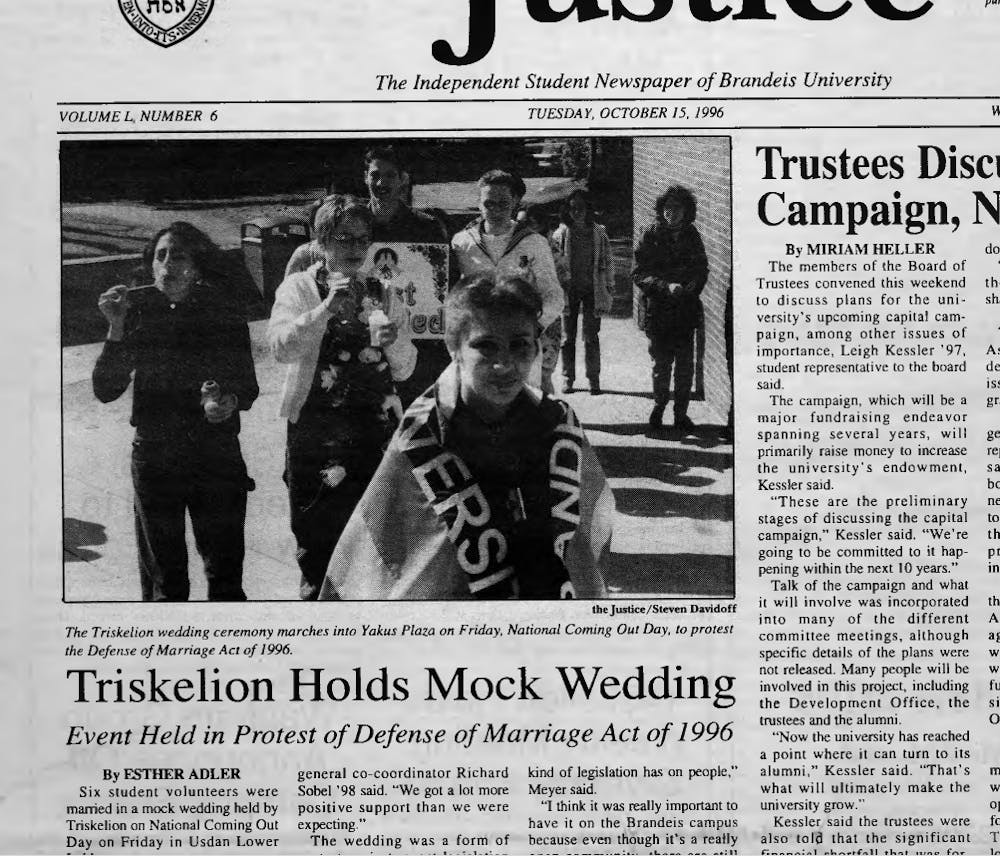

Oct. 11, 1996: Lower Usdan becomes the hottest new marriage venue

On Friday, Oct. 11, as a part of National Coming Out Day, six student volunteers were married in a Lower Usdan mock wedding before an audience of approximately 150 people. The event was put on by Triskelion, a campus organization for queer students, and was performed as a form of protest against the just-signed Defense of Marriage Act, according to an Oct. 15 Justice article. The act allowed states to refuse to recognize same-sex marriages that were performed in other states.

“I think it was really important to have [it] on campus because even though it’s a really open community, there are still people who are homophobic,” said Rebecca Polleck ’98. “It was a kind of step to show that homosexual love is just as valid as heterosexual love,” said Amara Whitham ’99, one of the wedding volunteers.

The student volunteers proceeded through Lower Usdan where participants read aloud the Marriage Resolution of the Lambda Legal Defense Fund, which supported queer and same-sex marriages. “I think some of the people who walked by and saw it were really affected because it’s not the norm for them,” Pollock said of the ceremony.

Triskelion also planned a multitude of events outside of Oct. 11 for National Coming Out Week, including facilitated discussions and a “Camp Out With Trisk” night.

“People were really accepting,” said Rebecca Meyer ’99, who performed the ceremony. “We had a lot of support.”

Oct. 23, 1962: Students organize a “Drive-Around” to protest new driving regulations

University administration was set to enforce a new driving regulation in October of 1962. Under the rule, resident students would not be permitted to drive onto campus between 8:15 a.m. and 5:15 p.m.; students would also be prohibited from parking in the lot by the campus gymnasium. Commuting students would be allowed to continue to park on campus as usual. The Council Executive Board at the time, which was made up of students, had been “led to believe” that students would have the ability to park by the gymnasium before 5:15 p.m. and walk to the main campus from there, but discovered that there were no extra spaces in that lot and only cars with the proper stickers would be permitted to park there. I. Milton Sacks, the dean of students at the time, asserted that the new regulations served as a “safety precaution,” citing the dangers of cars speeding by the “academic quadrangle.” Before the protest happened there were already concerns, including from campus security officers who believed the new regulations would be difficult to enforce.

The Council Executive Board originally planned the protest to be at 4:45-5:15 p.m. on Friday, Oct. 12, 1962, and was endorsed by President Alan Rapaport ’63, Vice President Kenneth Kemper ’63, Treasurer Donald Newman ’63, and Justice editor and Council representative Larry Goldman ’63. It was eventually rescheduled for the next Wednesday at 4 p.m. However, the drive-around was in danger of being canceled following an on-campus car accident less than 48 hours before the protest, in which a car containing two students skidded into a tree near the chapels. Goldman told the Justice that although “this accident does not affect the validity of the protest, at this time a demonstration would be most inopportune.” The Council eventually endorsed the protest by a 6-2-2 vote, and it went on scheduled.

The “car-picket” took place on Wednesday, Oct. 17. 45 cars and over 100 students drove around the campus with their headlights on until 5:15 p.m. Under the protested regulation, such driving on campus was illegal until 5:15, but security made no effort to stop the protest. One professor was even reported to have canceled his class so students could participate. The regulation was supposed to go into effect on Oct. 15, 1962, but “no effort was made by Security to enforce it,” nor was it enforced following the drive-around. A spokesman for the Committee of Public Safety deemed the picket a “success” and stated that the regulation was now a “dead letter.”

Oct. 29, 1986: Students plan to strike against University complacency in apartheid regime

On Oct. 29, 1986, the Justice covered student plans to protest against the University’s refusal to divest from businesses profiting in South Africa through an Oct. 31 mass absence from Friday classes. Writer Peter Joshua reported that the boycott was organized the week prior to Oct. 31 to stand in solidarity with Black students living under the racist policies of the South African regime known as apartheid.

Nine years earlier, Shelly Pittman ’79 had helped to create the Committee for Divestment from South Africa, an organization that pushed for the University to sell its stock holdings in companies working in South Africa. But by the late 1980s, the University had still not fully divested. “You still haven’t done it [divestment] around here?” responded former Massachusetts state governor Mike Dukakis when asked about the issue by students during a separate speaking event, according to the article.

Spearheaded by the Brandeis Divestment Coalition, the boycott offered action items in the place of classes. Reportedly, 40% of the student body polled said they were planning to participate, a number that the Coalition and other involved students hoped would rise.

In lieu of classes, on-campus screenings of Mandela (1986) and Witness to Apartheid (1986) were set to show on campus, as well as a guest-speaker event hosting Massachusetts Institute of Technology professor Mel King, former congressional candidate George Baruch, the daughter of Nobel Peace Prize recipient Naomi Tutu, African National Congress representative Themba Villakenzi, and chairman of the African and AfroAmerican Studies Department Wellington Nyangoni. Reportedly, Boston mayor Ray Flynn and daughter of Nelson Mandela, Maki Mandela, expressed interest in speaking as well.

“It’s a social obligation that overrides the need to go to classes,” said student Andrew Evans of the strike.

Please note All comments are eligible for publication in The Justice.