I guess the joke’s on me: ‘Joker’ sequel goes mad, but not in a good way

Content Warning: This article contains references to instances of sexual assault

This film was a “hard watch” in the most literal of senses.

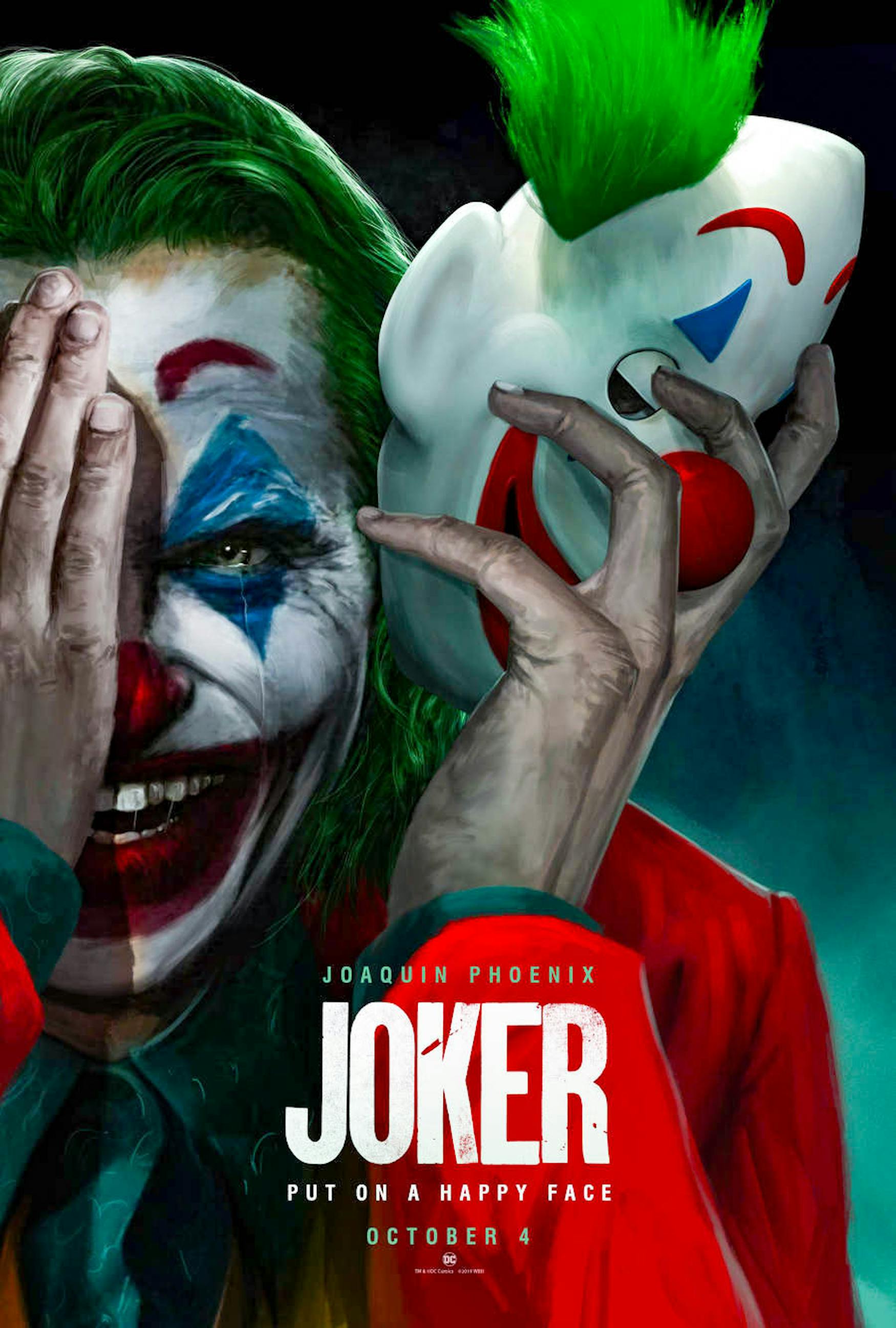

In “Joker: Folie à Deux,” the highly anticipated sequel to Todd Phillips’ 2019 film “Joker,” Joaquin Phoenix returns once again as Arthur Fleck, better known as the Joker. This sequel explores the next chapter in Arthur’s life, delving deeper into his chaotic descent into madness. The title, “Folie à Deux” — meaning “shared madness” — alludes to the toxic relationship between Arthur and Harley Quinn, portrayed by Lady Gaga.

The film introduces musical elements, which add an unconventional angle to the narrative, reflecting both the deteriorating mental states of the characters and the unsettling nature of Quinn and Fleck’s relationship. Like the first film, “Joker: Folie à Deux” strives to be dark, psychological and emotionally intense, focusing on themes of mental illness and society’s disregard for those it deems unworthy.

However, despite its potential for innovation, the film ultimately falls short in execution. From its disjointed narrative to its questionable portrayal of marginalized communities, “Joker: Folie à Deux” misses the mark. Many scenes that appear intended as satire or social commentary fail to land, leaving viewers unsure of what the film is truly trying to say. Instead of offering meaningful insights, the film feels shallow and disconnected from the weighty issues it seeks to address.

WARNING: SPOILERS AHEAD

Before delving into the aspects of the film that I found disappointing, I want to highlight what I appreciated and found compelling.

To begin, the cinematography and color grading in “Joker: Folie à Deux” are visually stunning. The film features breathtaking shots, particularly within the court sequences and the musical scenes between Joker and Harley Quinn, which are beautifully vibrant and evoke a clear homage to Technicolor musicals of the 1950s and 60s. The costume design also deserves recognition — Joker’s constantly changing suits are striking, while Harley Quinn’s subtle evolution into a version of her iconic costume depicts the subtle evolution of her character.

I appreciated how the film’s visuals reminded me of classic Hollywood musicals centered around doomed romances, such as “One From the Heart” (1981), “The Umbrellas of Cherbourg” (1964) and “La La Land” (2016). It appears Phillips aimed to use the visual language of musical sequences, often depicting characters dissociating from their bleak realities to escape into a fantasy to illustrate Arthur’s delusions of grandeur. While the film never fully commits to the fantastical musical numbers that the aforementioned films embrace throughout, it’s evident that the director intended to use this style to signify Arthur’s growing detachment from reality and foreshadow the inevitable unraveling of his relationship with Harley.

This approach felt like a subversive and intriguing direction for this sequel. However, the film’s inability to fully commit to the musical elements ultimately undermines what could have been a unique vision. The sporadic musical numbers felt jarring, disrupting the movie’s momentum rather than enriching it. Instead of offering deeper insights into the characters’ thoughts or motivations, these scenes felt out of place, and at times, even disrespectful to Arthur’s trauma. Had the film fully embraced the musical angle, it might have salvaged some of the more questionable choices, elevating the story rather than leaving it muddled and half-hearted.

Now, onto elements I found problematic about “Joker: Folie à Deux.”

The filmmakers invest a significant amount of time shaping Arthur into a character audiences can empathize with — someone struggling with his mental health — only to break him down in the most appalling ways. It’s not just the cruel characters around him mistreating him, but a sense of cruelty from the filmmakers themselves in choosing to depict these scenes. The relentless humiliation Arthur endures feels excessive and exploitative, rather than insightful.

Throughout the film, there’s an uncomfortable tendency, both in dialogue and visual language, to ridicule those who are physically or mentally disabled. Arthur, a character suffering from severe mental illness, is never given the space for the audience to truly understand how his trauma and mental state inform his decisions, particularly those from the first film. Instead, the movie opts to show Arthur continually being humiliated, whether by the criminal justice system or those around him, for his poor grasp on reality and misunderstanding of others. While it seems like the filmmakers are attempting to comment on society’s mistreatment of the mentally ill, it never lands as social critique or even satire — instead, it comes across as ridiculing Arthur’s mental health struggles.

This disrespect extends to Arthur’s former co-worker, Puddles, played by Leigh Gill, a little person whose stature is repeatedly played for comedic effect, even in traumatic situations. Instead of addressing Puddles’ pain or acknowledging the impact Arthur had on him, the filmmakers exploit his stature for humor. There’s a particularly distasteful moment where the camera lingers on Puddles struggling to get into the witness seat, using a slow pan up from behind to emphasize his small size as he sits on a phone book — while the room giggles and Arthur mocks him for being small. This type of visual humor is not only inappropriate but undermines any serious exploration of trauma or victimization.

Perhaps the most disturbing and egregious scene comes toward the end of the movie when Arthur, after fleeing from his trial, is captured by the police. In a horrifying moment of thinly–veiled sexual assault, the lead guard, played by Brendan Gleeson, offended by Arthur’s comments about him during the trial, orchestrates a brutal attack. He gathers his fellow officers to beat Arthur, strip him and drag him into the showers, where it is heavily implied they assault him. The next scene shows them dragging his limp, bruised body back to his cell, with Arthur staring vacantly ahead, completely broken.

Despite the harrowing nature of this scene, there is no point in the film where the guards face any consequences for their actions or have any room to unpack what happened. It feels as though the filmmakers are complicit in this constant humiliation and victimization of its characters, as they never address the abuses Arthur suffers, nor do they give these perpetrators any form of punishment, either direct or thematic.

Ultimately, “Joker: Folie à Deux” presents a dangerous misrepresentation of mental illness, portraying victims of trauma and mental health struggles as violent or deserving of punishment. In its attempt to comment on society’s failures in supporting these individuals, the film ends up failing them as well — turning their suffering into spectacle rather than offering any meaningful exploration or resolution.

Please note All comments are eligible for publication in The Justice.