The beauty of silent cinema, as seen through the lens of ‘The Cameraman’

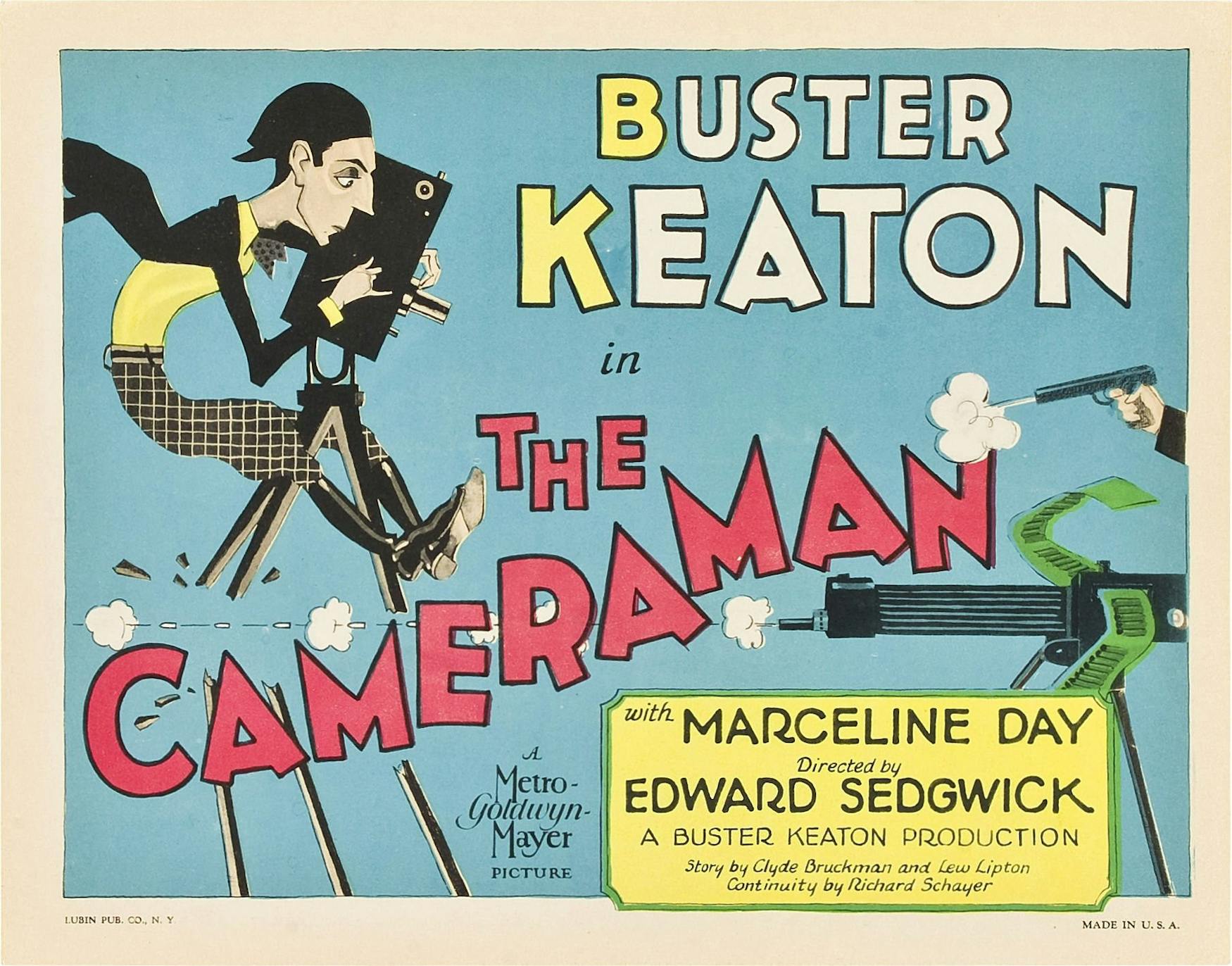

In 1928, silent film titan Buster Keaton and Edward Sedgwick co-directed the film “The Cameraman,” which was also Keaton’s first film after signing to Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer. The movie follows a young man named Buster — played by Keaton — as he attempts to secure a job at a newsreel agency in order to get closer to a girl who works there. It is considered by many to be among Keaton’s finest films and is most certainly one that encapsulates not only the zeitgeist of the 1920s, but the beauty of the era’s silent film. In its one hour and nine minutes, audiences get a glimpse into the world of the 20s and some of the wittiest displays of comedy that Keaton has to offer.

The film is interesting not only as a work of art but also as a snapshot into American life during the 1920s. Keaton plays a young photographer who specializes in a form of street photography known as a “tintype,” where for a small fee he will take a person’s picture — with a very large and bulky camera — and imprint the image onto a small tin plate. This is one of many details of the film that help encapsulate the era and allow us to appreciate the technology and culture of the past. Today’s viewers, who can store thousands of photos on a phone, are likely totally foreign to something like a tintype and might appreciate this snapshot into the past.

Another key aspect of cinema in the “Roaring Twenties” is the shift in on-screen portrayal of female sexuality, which in turn represented a change in what was acceptable for women to do on and off-screen. The main love interest of “The Cameraman,” Sally, is very forward with the protagonist — she is the one to ask him out on their first date and is very flirtatious, unashamed to express romantic interest. This may seem relatively tame, but compared with the typical Victorian-style women portrayed in earlier cinema, this is quite profound. Earlier films wrote women to be demure and withdrawn, neither desiring others nor to be desired herself. This is exactly the opposite of Sally and another reason why “The Cameraman” is such an interesting film from a historical and cultural point of view.

“The Cameraman” further establishes a flourishing consumer economy and vibrant way of life associated with the 20s; the main couple is able to spend money on buses and purchase tickets to a public pool, people on the street have spare change for tintypes and the news agency where Keaton attempts to secure a job is thriving. Of course, a year later would bring the worst economic recession in U.S. history; within the world of “The Cameraman,” however, a hopeful era of exponential growth and productivity is captured.

Aside from the film’s historical and cultural relevance, it is also simply an example of truly excellent silent cinema. Even for someone with no experience in the realm of silent film, Keaton’s brilliant use of comedy and stunt work draws in the viewer’s attention and retains it. One interesting example of this is a several minutes-long shot, undisturbed by anything save for the caption cards, in which Buster and another man struggle to get changed in the same cramped dressing room. In modern cinema, it would be difficult to find a long scene such as this with no editing, camera movement or dialogue. Keaton makes it work, though; his knack for physical comedy removes the need for anything more complex than what is going on between these men in the tiny box within the camera’s frame. Throughout the film, Keaton’s forever-iconic stunts, bits and gags — riding on the wheel of a bus, repeatedly breaking windows with his camera or blundering his way through a gang war — demonstrate the genius of silent comedy.

Good camerawork also plays a strong role in this art form. For instance, one shot towards the beginning of the film starts as a closeup of the two main characters, Sally and Buster, standing side by side, only to zoom out revealing the comic disarray of the street around them following a raucous parade. Or, take the segment where Buster continues to run up and down the stairs in order to receive a phone call from Sally; the camera expertly moves up and down next to him as he frantically ascends and descends. While humorous camerawork is still well and alive today, the camera was an especially important character in many silent gags which needed to retain attention through solely visual means.

Written dialogue is used where necessary, but not heavily relied upon. Silent stars like Keaton were forced to entertain an audience without using our most common mode of communication: speech. “The Cameraman” is a prime example of how what may be viewed as a weakness of silent film becomes a great strength — the lack of sound gives way to an utterly unique and timeless form of comedy that cannot be replicated in the age of sound.

It is easy to assume that as film technology improves, so does the quality of the movies made with it. This is far from accurate, of course. It is true that fantastic things can be done now with more advanced methods of filming and editing, but do not let this detract from the accomplishments of early cinema. Living in an era of sound cinema, it is in a way even easier to appreciate the genius that went into the great silent films, and the stories they so vividly tell with far simpler, though still impressive, machinery. The lack of sound and color does not make silent movies inferior; rather, it lends them a special quality and charm that sound movies cannot capture. On top of this, these silent films give us an important portal through which we can analyze shifting norms, mindsets and cultures. Sedgwick and Keaton’s “The Cameraman” perfectly exemplifies these attributes, creating a totally distinct viewing experience — especially for someone who has grown up in the age of sound cinema.

Please note All comments are eligible for publication in The Justice.