‘The Color of Pomegranates’: The beauty of weirdness in crafting impactful narratives

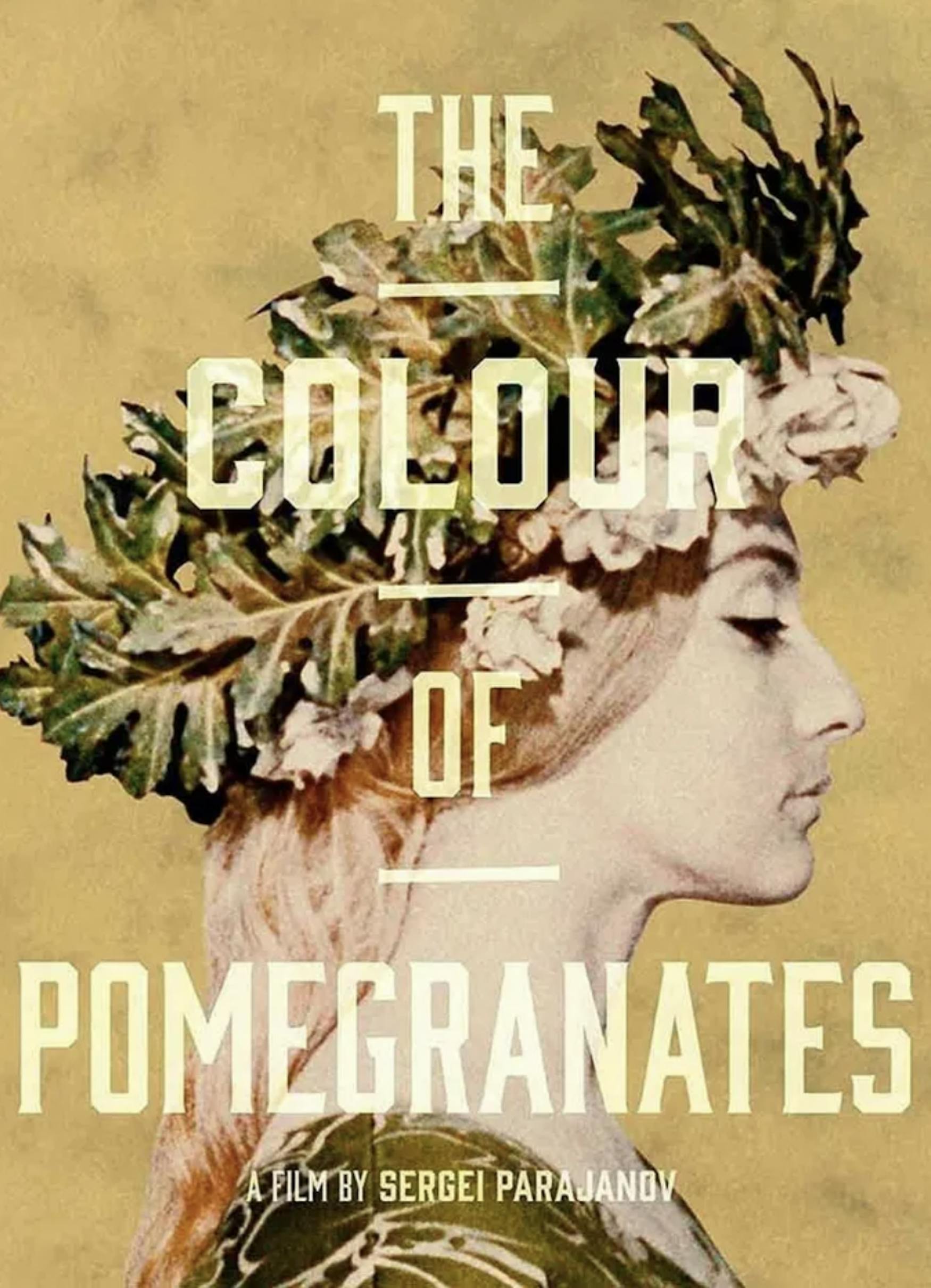

Sergei Parajanov’s film, “The Color of Pomegranates” is truly groundbreaking with its interesting filming techniques, storytelling choices and iconic overall aesthetics. Parajanov’s ability to mesh the story of Sayat Nova, a famous Armenian artist and poet, with historical aspects of his culture made the movie a staple in filmmaking and in the Armenian diaspora. His images and film style appealed to the many surrealist filmmakers at the time and yet his visions for the film didn’t align with the beliefs of the Soviet government, resulting in the ban of the film for over 50 years. Despite this, filmmakers all over the world today refer to the movie as one of the most influential of its time. No matter if you watch the first or second version of the restored films, Parajanov’s vision remains clear. The unconventional narrative techniques of Parajanov’s “The Color of Pomegranates” accentuate the weirdness and experimental nature of the film by adding depth and meaning that is only discernible by the audience themselves.

One of Parajanov’s most striking techniques within his films was the use of religious artifacts and iconography to convey specific narratives. “The Color of Pomegranates” was no exception. The use of Armenian artifacts, instruments and everyday items was extremely common in the film, with every scene featuring some collage of these pieces. Each scene in the film looks as though it is an image — a picture that is taken for the audience with no explanation. If you observe the scene about 21 minutes into the original film, there is a series of images set in front of a beige wall adorned with rectangular linens sewn together draped down in the center. A man wearing patterned clothing and a large horned hat appears in the center, banging on a drum between his legs as two statues on either side of the linens swing from side to side. The scene progresses and each of the ‘statues’ comes to life and take turns walking into the center of the scene and dancing with bowls and teapots in their hands. The film then cuts to the drummer again, only this time he is to the side of the scene and there is a boy jumping around with feathers in his hands. Even when observed in the broader context of the film, this scene is shrouded with mystery and intrigue. It makes the audience wonder what its relevance is in the grand scheme of Sayat Nova’s life and how they are supposed to interpret it. Some of the answers to the audience’s questions come from the analysis of the items that are hidden within the scene. The linens are recognizable Armenian patterns generally found in handmade carpets. The dancing individuals in the scene are wearing traditional Armenian wedding clothing. One interpretation is that this is Sayat Nova’s wedding to the girl he had been admiring earlier in the film. Despite these theories, the answer is never confirmed for the audience. They are left to wonder as they watch the rest of the film and search for other explanations for the many forms of surrealist imagery that are present. But the key to Parajanov’s experimentalist filmmaking is just that: the surrealist imagery is meant to confuse the audience and leave them with this sense of wonder. There is no specific answer that will completely satisfy the narrative that the audience is searching for. Rather, the mystery of the images in the film is what creates the narrative, which is where the weirdness of the film can truly shine.

Another aspect of the film that is notable is the lack of speech and dialogue in any of the scenes. Despite the fact that the film is meant to tell a story, Parajanov ensures that there is no real “telling” at all. Instead of using words to express the images, he lets the pictures speak for themselves and leaves the audience to decide the meaning on their own. That being said, Parajanov offers some aid through the specific bits and pieces of Sayat Nova’s compositions, both music and spoken poetry, to accompany the images that he presents. One of the most iconic scenes in the film is at about 30 minutes and focuses on a woman in traditional Armenian clothing threading thin strings together to create a lace pattern while standing in front of a swinging picture frame. In the next clip, a man stands facing forward, turning an instrument in front of the swinging picture frame. As the scene cuts from the woman to the man, there is a single note being played on the violin repeatedly and some of the only words in the entire film are spoken in Armenian as the narrator, Sayat Nova, says, “You are fire. Your dress is fire.” This phrase is repeated multiple times until the film moves on to the next image. These words come directly from a poem by Sayat Nova in which he expresses his love for a woman that he has seen and desperately wants to be with. Parajanov’s interpretation of the poem, mixing the visual aspects of the scene with the narration and background, creates a distinct experience for the audience. This experience is what makes “The Color of Pomegranates” so unique when compared to other films: it makes the audience feel what Sayat Nova’s poems are saying. The experience of the film is a huge part of the narrative because it is what encourages the audience to come up with their own conclusions about the film and pushes them to learn more about the director and his muse, Sayat Nova. It is unique in both its methods and in its visual cues that are jarring and impactful for the audience’s viewing. The usage of sound in this film once again enforces the idea that the experimental aspects of the film come from its openness to audience interpretation.

In many ways, the oddest aspect of this film is the fact that Parajanov himself sees it as a normal narrative, or so to speak. In an interview with Ron Holloway, he explains that his directing is “fundamentally the truth as it’s transformed into images: sorrow, hope, love, beauty.” He explains that the stories he incorporates into his films are not made up as many people think they are and he responds to these individuals by saying, “No, it’s simply the truth as I perceive it.” In a sense, the surrealist take that Parajanov uses to create his film “The Color of Pomegranates” is simply his authentic interpretation of the true life of Sayat Nova. It is his life through the artistic lens of Sergei Parajanov. He doesn’t necessarily denounce realism either, as he sees it as a means to reach surrealist art. He says that there are “different ways to give the impression of ‘hyper-realism.’ If I needed a tiger, then I would make a tiger out of a toy and it would have more effect than a real tiger would have.” The forms in which Parajanov chooses to create the worlds in his films are surrealist and yet the ideas behind them seem to be so elementary. This, however, is what creates the experimentality of “The Color of Pomegranates.” It creates the idea that an artist can create the surreal from the real and weave their story’s imagery in such a way that each viewer interprets it differently, even in a time in which individualism was discouraged.

The impact of Parajanov’s “The Color of Pomegranates” is still seen in many forms of media today. Its experimental narrative and form have allowed it to become a commonly referenced film for artists such as Lady Gaga, movies such as “Midsommar” and other filmmakers like Wes Anderson. At its core, the surrealist ideas and filmmaking techniques used in “The Color of Pomegranates” are representative of the impact of film on social movements today by allowing others to offer their own interpretations and ideas based on their own experiences. Parajanov’s bravery and determination to create films despite the attempts to keep him silenced is a perfect example of what it means to be experimental and to question the standards that are imposed on art and literature. The beauty of his film in conjunction with its weird narrative creates an unforgettable story and a timeless film that will foster further analysis for generations to come.

Please note All comments are eligible for publication in The Justice.